Chapter 8:

Teaching and Learning

Goals

The University of California provides its students with a rich learning environment created by faculty who are actively engaged in both teaching and academic research. Student learning experiences at UC involve classes, seminars and lab sections enhanced by opportunities to collaborate with experienced faculty and researchers in hands-on research projects. Through these activities, faculty and students engage in a learning process that helps students develop critical thinking, communication and problem-solving skills, as well as discipline-specific knowledge that future employers value.

Educating students and the public

UC’s faculty are principally responsible for maintaining UC’s academic excellence and achieving student success. Crucial measures of faculty effectiveness are student retention and graduation rates, presented in detail in Chapter 3. This chapter focuses on the composition and workload of instructional staff — full-time permanent faculty, lecturers, visiting faculty, adjuncts and other instructors — across different academic disciplines and professional programs. This chapter also considers the learning experience of UC’s undergraduate students, reporting their engagement with faculty and self-evaluation of their UC experience. A majority of students report improvement in academic skills and a deeper understanding of their chosen field of study.

Under California’s Master Plan for Higher Education, UC is responsible for educating doctoral and professional students. This chapter describes UC’s faculty involvement in awarding doctoral degrees and provides comparisons with other public and private members of the Association of American Universities (AAU).

Expanding learning opportunities beyond students on campus is an important contribution of UC and demonstrates the connection between the teaching and the public service missions of the University. UC Extension offers adult professional and continuing education programs to Californians and people around the world. In 2015–16, there were 400,000 UC Extension course registrations.

UC also operates a wide range of public education programs through the Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources (ANR). One flagship program is the 4-H Youth Development Program, which provides enrichment education to 200,000 youth statewide through inquiry-based learning. Chapter 10 describes ANR’s community programs and statewide impact in more detail.

Promoting educational effectiveness

UC is committed to continuous improvement of instruction and employs a range of pedagogical and assessment strategies to enhance and support student learning. Campuses offer pedagogical development and training for faculty and teaching assistants to promote the use of evidence-based teaching practices and improve the quality of teaching and learning. Collectively, UC’s teaching and learning centers and offices of instructional development train hundreds of instructors each year, thereby improving the quality of education for students in all disciplines and across all ten campuses.

UC has made great strides in promoting educational effectiveness by supporting assessment of student learning in academic programs. Assessment strategies include the development of student learning outcomes and integration of evidence of student learning into academic program reviews. Assessment efforts across UC align with the expectations of regional accrediting agencies, in particular the WASC Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC). As part of WSCUC accreditation, UC campuses assess five main core competencies of student learning: writing, oral communication, quantitative reasoning, information literacy and critical thinking. Each UC campus makes its WSCUC accreditation reports public, posting them online.

Innovative instructional offerings

UC offers an ever-expanding catalog of online courses and online programs, expanding learning opportunities for undergraduates, graduates and professional students. These courses and programs offer increased learning options for UC and non-UC students. Through the UC cross-campus enrollment system (http://crossenroll.universityofcalifornia.edu), UC provides undergraduates access to high-demand courses offered at other UC campuses, providing students increased flexibility and opportunities to complete their degrees. UC online courses are developed and taught by UC faculty at campuses across the system and count for UC credit based on departmental and programmatic requirements.

For non-UC students who are considering matriculation at a four-year university or are resuming their studies, UC offers for-credit online courses that may transfer to other colleges and universities. UC Online (http://www.uconline.edu) provides courses that span a wide range of disciplines, from psychology to languages to STEM courses. UC Extension offers online continuing education courses, professional certificates and post-baccalaureate programs for those seeking to advance their education and to enhance their professional skills.

In addition to online courses, UC leverages innovative instructional technologies to enhance instruction and promote student success. UC continues to develop and refine high-quality hybrid courses using multimedia resources, videos, podcasts, e-books and other technology-based tools to enrich students’ learning experiences. UC follows best instructional practices to embed innovative technologies into course design and focuses on creating online and face-to-face learning experiences that encourage collaboration and maximize faculty-student and peer-to-peer interactions. Increasingly, UC courses utilize a flipped model of instruction, where lectures and other traditional classroom content are provided online, and classroom time is dedicated to group discussions and problem-solving activities, and other experiential exercises.

UC is enhancing student learning opportunities and success by expanding summer course offerings (in-person and online) to reduce students’ time to degree and enrich their academic experience. Offering bridge experiences and orientation during summer also helps incoming students transition to campus life and prepare them for the rigorous courses at the undergraduate level.

For more information

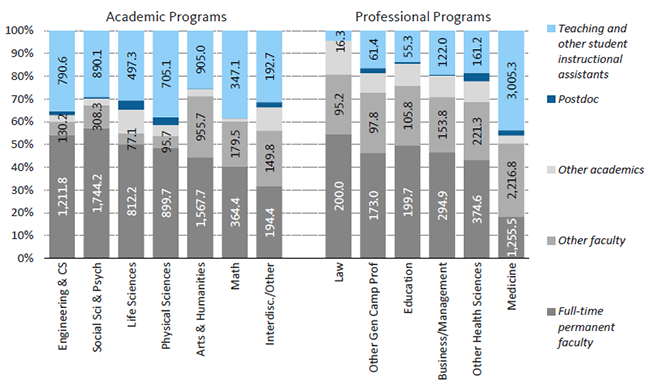

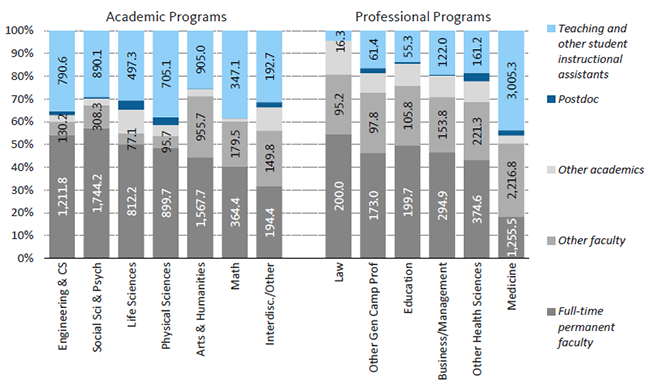

The composition of the instructional workforce varies considerably by discipline, with full-time permanent faculty representing about half of the workforce for general campus instruction.

8.1.1 Instructional workforce FTE composition, by employee type and discipline, Universitywide, 2015–16

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System1

Across all general campus disciplines at UC, full-time, permanent faculty constitute about 49 percent of the total instructional workforce. Fields where full-time permanent faculty represent more than 50 percent include Engineering & Computer Science, Social Science, Psychology, Life Sciences and Law. Medical education, however, relies more heavily for instruction on faculty who also have clinical roles, and the proportion of full-time permanent faculty in Medicine and Other Health Sciences comes to 21 percent.

“Other faculty” in this indicator includes clinical faculty, most lecturers, adjunct faculty, faculty in residence and visiting faculty. The “Teaching and other student instructional assistants” category refers to students acting in supporting roles, such as teaching assistants, readers and tutors. They typically lead labs and discussion sections for large lecture courses. The “Other academics” category includes administrators and researchers who have instruction functions.

Because full-time permanent faculty have scholarship and research experience, their instruction is a valuable part of a student’s learning experience. When faculty incorporate their early research results into their courses, UC students gain access to insights and discoveries even before they are available to the wider research community.

1Academic support staff, such as clerical staff, administration and advisers, including students working in these titles, are excluded. Data are for full-time-equivalent number of academic employees paid with instructional funds.

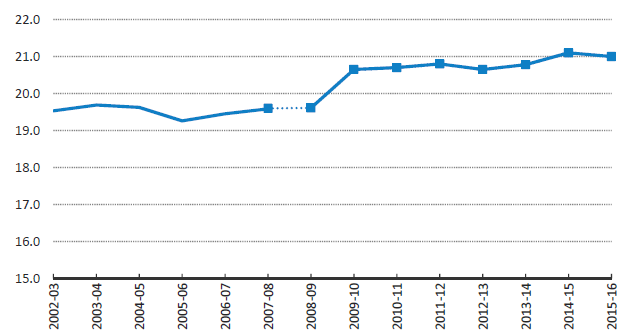

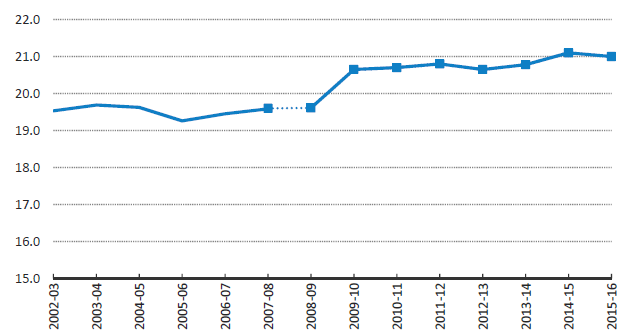

The student-faculty ratio increases when faculty hiring does not kept pace with increases in student enrollment.

8.1.2 General campus student-faculty ratio, Universitywide and UC campuses, 2002–03 to 2015–16*

*A revised methodology for calculating the student-faculty ratio is used beginning in 2008–09. Previously, UC calculated this ratio by including only faculty supported by core funds (comprising state general funds, UC general funds, and tuition and fees). Starting with 2008–09, the ratio calculation includes faculty paid through all fund sources (other than self-supporting program fees). This change in methodology better reflects recent increased flexibility in use of fund sources to pay faculty.

Source: UC Information Center Data Warehouse

One widely used measure of academic quality is the student-faculty ratio. The student-faculty ratio reflects resources available for instruction and the average availability of faculty members to every student. Thus, lower ratios are preferable for students in terms of focused resources for instruction.

Because the student-faculty ratio varies considerably by degree, major and instructional level (lower-division, upper-division and graduate), student experiences will vary as well. Indicator 8.1.3 on student credit hours (SCH) provides additional insight into the student experience.

The student-faculty ratio has increased at various times in the University’s history and particularly in the last decade. During the most recent recession, campuses responded to uncertainty in state funding by delaying faculty hiring, or deciding not to fill vacant faculty positions on a permanent basis.

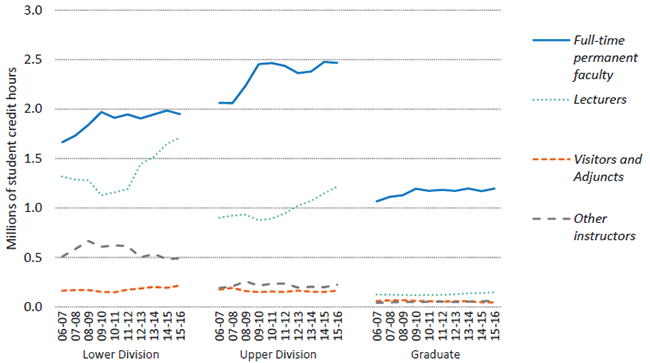

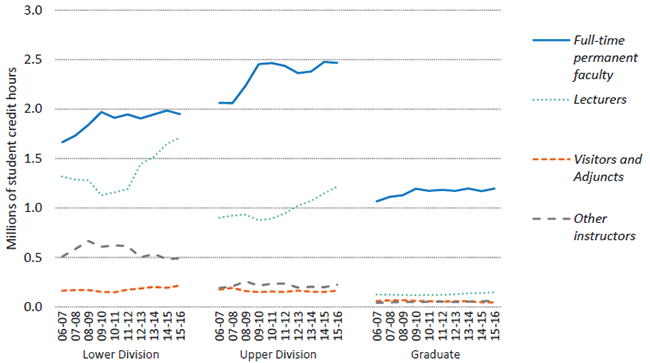

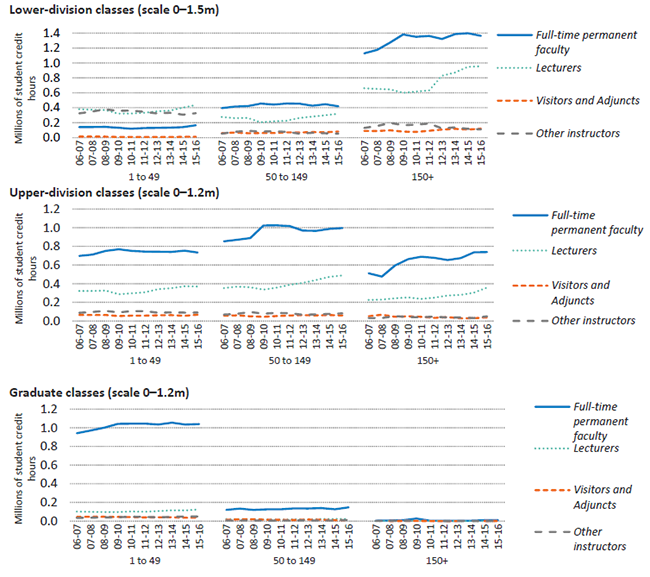

As a group, lecturers are teaching increasing numbers of student credit hours in both undergraduate and graduate levels.

8.1.3 Student credit hours, by instructional staff and class type, Universitywide, 2004–05 to 2015–16

Source: UC Faculty Instructional Activities dataset1

Student credit hours (SCH) represent the number of student enrollments in a course multiplied by the number of credits earned from that course. For example, a 4-credit class with 50 students generates 200 SCH; a 2-credit class with 15 students generates 30 SCH. This measure gives an indication of the relative teaching load across different types of instructors at different levels of instruction.

Over time, the full-time permanent faculty at UC have increased their teaching load and maintained contact with more undergraduate and graduate students. Overall, a larger number of student credit hours performed by full-time permanent faculty means students have additional opportunities to be taught by leading scholars in their disciplines.

Lower-division courses, such as writing, language and other required courses, are most often taught by lecturers; introductory courses to the major are most often taught by full-time permanent faculty. Upper-division courses, which are core to the student’s major, are more likely taught by full-time permanent faculty, as are graduate courses.

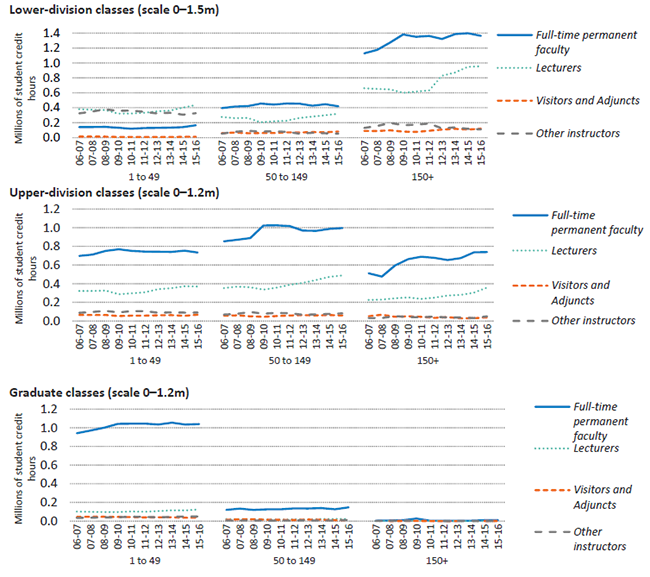

As students progress through their academic careers and enroll in upper-division and graduate classes, they receive more consistent exposure to full-time permanent faculty and smaller classes.

8.1.4 Student credit hours, by instructional staff and class type and class size, Universitywide, 2004–05 to 2015–16

Source: UC Faculty Instructional Activities dataset

In the lower division, full-time permanent faculty generally teach large lecture classes; nonpermanent faculty, such as lecturers, generally teach lecture sections and smaller classes. In the upper-division, student contact with full-time permanent faculty is fairly evenly distributed across classes of all sizes.

Graduate academic students are almost uniformly taught by full-time permanent faculty in classes with fewer than 50 students.

8.2 Summer enrollment

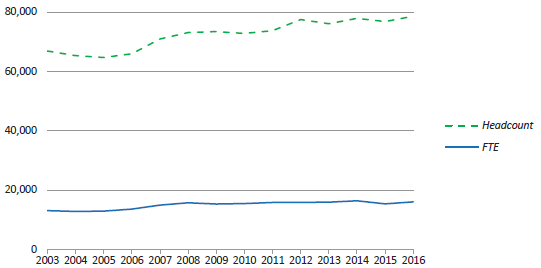

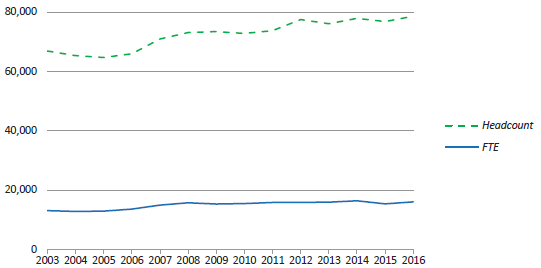

Summer enrollment has increased since 2003.

8.2.1 Summer enrollment, Universitywide, 2003 to 2016

Source: UC campuses

Over a decade ago, the University of California began expanding summer instruction programs with full support and funding from the state. From 2003 to 2016, headcount and FTE summer enrollment increased by 22 percent and 18 percent, respectively.

Across all UC campuses, many students enroll in summer session to finish the coursework required for graduation. Expanded summer sessions have contributed to notably increased four-year graduation rates.

The federal government does not currently provide Pell Grant funding for summer enrollment. Because 38 percent of UC students rely on Pell support (as of fall 2016), these students may find it difficult to take advantage of summer classes and maintain timely progress to degree.

However, in an effort to eliminate financial hurdles and increase summer session access for all students, campuses continue to set aside a portion of summer revenues for financial aid. In summer 2016, campuses provided 29,899 students with $79 million in need-based financial aid, including $56 million in grants and scholarships. As part of the 2015 state budget agreement, three UC campuses piloted alternative pricing models for the 2016 summer session. These pilots assessed options to encourage more undergraduates to take more courses during the summer.

In addition, UC summer session supports 11,000 non-UC students, including many CSU and CCC students.

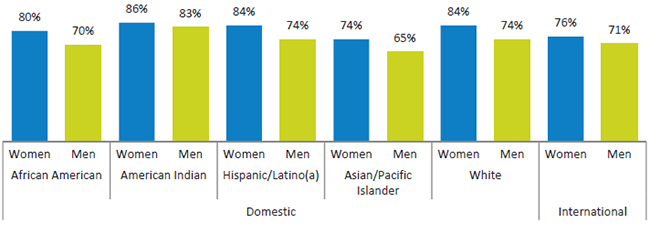

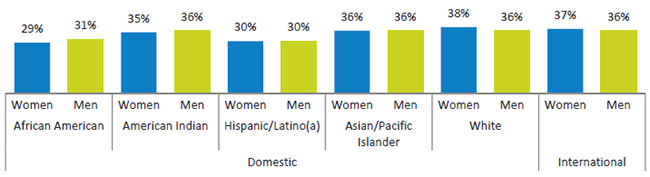

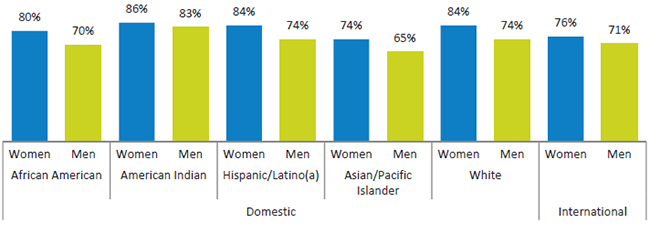

Research participation is high among UC’s seniors across racial/ethnic and gender groups.

8.3.1 Students completing a research project or research paper as part of their coursework, Universitywide seniors, Spring 2016

Source: UCUES

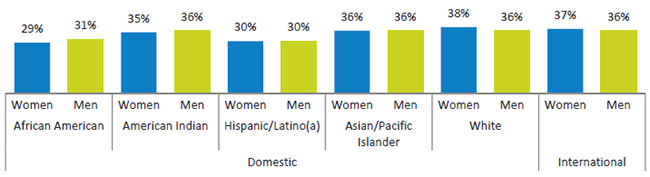

8.3.2 Students assisting faculty in conducting research, Universitywide seniors, Spring 2016

Source: UCUES

One of the distinct benefits of attending an academic research university is the opportunity for undergraduates to conduct research, both through class research projects and by assisting faculty with their ongoing research.

Overall, a high percentage of undergraduates reported that they participated in research. Women were more likely than men to indicate completing a research project or paper as part of their coursework. However, there was no difference in the proportion of women and men who reported having assisted faculty with research. Both of these findings held across racial/ethnic groups.

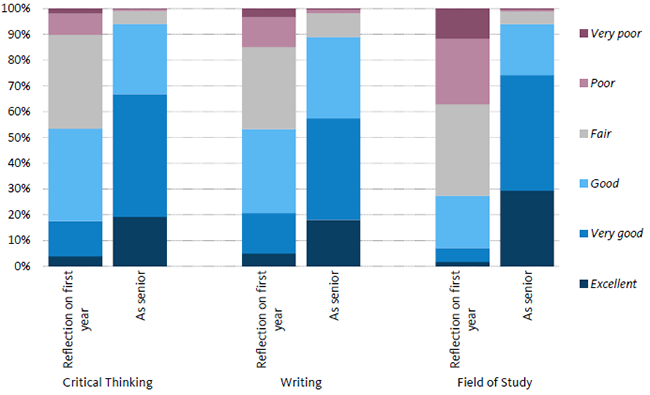

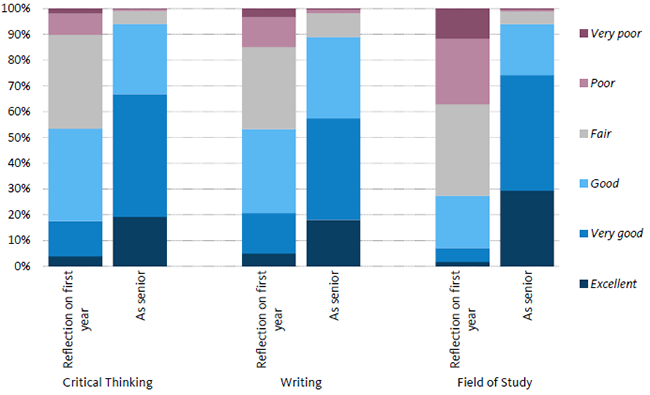

UC students experienced significant improvement between their freshman and senior years in critical thinking skills, writing skills and understanding of their chosen field of study.

8.4.1 Self-reported skill levels from first year to senior year, Seniors who entered as freshmen, Universitywide, Spring 2016

Source: UCUES

The University of California Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES), which is conducted every two years, provides a valuable source of information on how UC undergraduates view their educational experience. These indicators also show student perception of how much they have developed core competencies of student learning.

Reflecting on their skill levels between their freshman and senior years, UC students self-reported significant improvements with respect to critical thinking ability, writing and understanding of their chosen field of study.

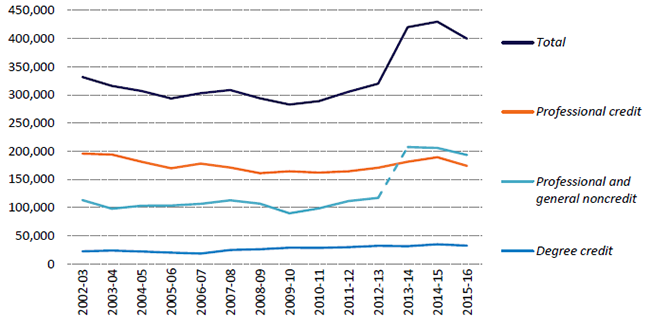

UC is a significant provider of post-college continuing education to Californians.

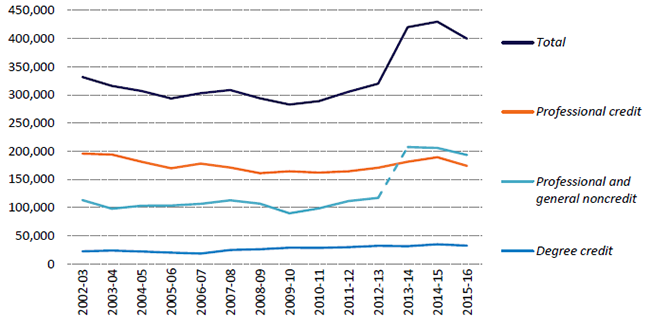

8.5.1 Continuing education enrollments in extension programs,

Universitywide, 2002–03 to 2015–16

Source: UC Extension Financial Statements1

UC Extension is the largest continuing education program in the nation. It provides courses to individuals who want to continue their education beyond their undergraduate studies, advance in their professions, change careers, engage in further academic pursuits and improve their skills in current or new endeavors. Extension’s highly diverse range of courses offers specialized programs of study, and provides both credit and noncredit certificate programs.

UC Extension is completely self-supporting. Each campus extension division addresses the particular educational needs of its geographic area. For example, UC Riverside Extension offers a Professional Certificate in Turfgrass Management program; UC Davis Extension offers a Winemaking Certificate Program.

Extension enrollment fluctuates with the economy; enrollment numbers decreased during the 2007–09 recession, for example. There was a steep increase in noncredit enrollment in 2013–14 because outreach in-service courses were included for the first time. These programs may satisfy continuing education requirements of public agencies and professional associations but do not convey UC Academic Senate-approved credit.

1 “Degree credit” courses lead to formal UC degree credit, developed and presented in partnership with campus faculty and degree programs. “Professional credit” courses provide Academic Senate-approved academic credit but are not associated with a specific UC degree program. “Professional and general noncredit” courses are high-quality continuing education courses and workshops.