chapter spotlight

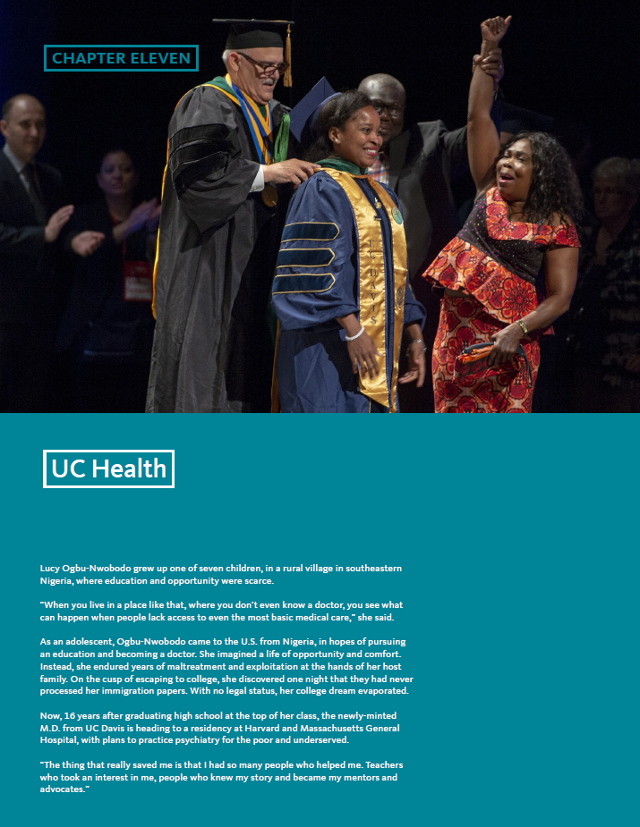

Lucy Ogbu-Nwobodo grew up one of seven children, in a rural village in southeastern Nigeria, where education and opportunity were scarce.

“When you live in a place like that, where you don’t even know a doctor, you see what can happen when people lack access to even the most basic medical care,” she said.

As an adolescent, Lucy Ogbu-Nwobodo came to the U.S. from Nigeria, in hopes of pursuing an education and becoming a doctor. She imagined a life of opportunity and comfort. Instead, she endured years of maltreatment and exploitation at the hands of her host family. On the cusp of escaping to college, she discovered one night that they had never processed her immigration papers. With no legal status, her college dream evaporated.

Now, 16 years after graduating high school at the top of her class, the newly-minted M.D. is heading to a residency at Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital, with plans to practice psychiatry for the poor and underserved.

“The thing that really saved me is that I had so many people who helped me. Teachers who took an interest in me, people who knew my story and became my mentors and advocates.”

health expertise in service of three missions

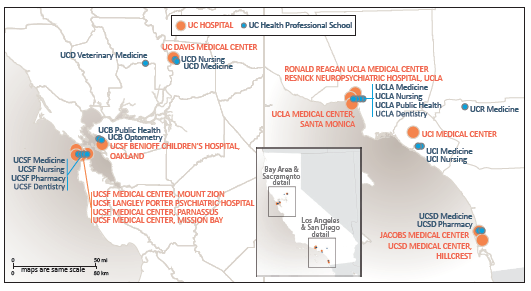

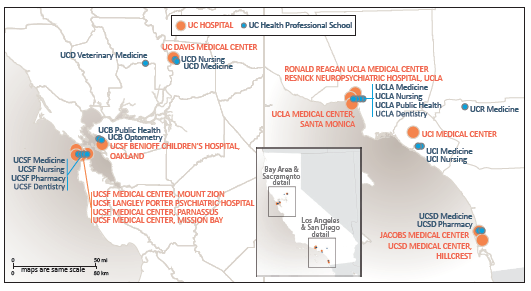

The University’s 18 health sciences schools, six health systems, student health centers, and self-funded health plans are connected by UC Health, the division office within the Office of the President. The activities of the division, and the larger health enterprise, are aligned to support the University’s three missions of public service, higher education, and research — in the case of UC Health — in pursuit of new cures and treatments.

boldly caring — training california's future health care professionals

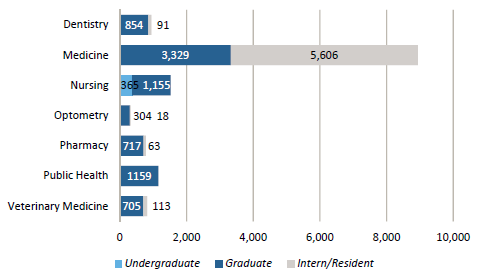

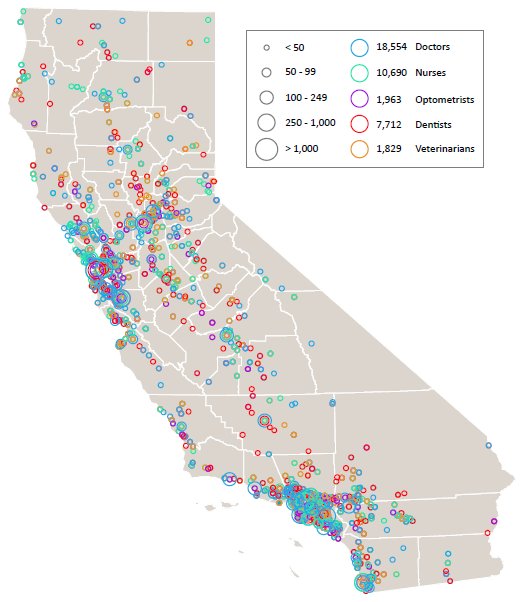

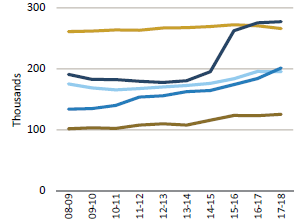

Nearly 15,000 students are enrolled in UC’s health sciences schools or residency programs. This next generation of health care providers is an important part of California’s future, as the population grows, ages, and becomes ever more diverse (11.1.1).

Approximately 72 percent of UC health science students and 61 percent of medical residents are expected to remain in the state after completing training or education. This high rate of retention makes UC Health one of the principal sources for the training of California’s health professionals (11.1.2).

UC’s health sciences schools are:

- Dentistry (UCSF, UCLA)

- Medicine (UCD, UCSF, UCLA, UCR, UCI, UCSD)

- Nursing (UCD, UCSF, UCLA, UCI)

- Optometry (UCB)

- Pharmacy (UCSF, UCSD)

- Public Health (UCB, UCLA)

- Veterinary Medicine (UCD)

UC’s health science schools are among the best in the nation, according to U.S. News & World Report 2019 rankings.

US News & World Report’s “Best of” Rankings as of 2019:

| |

UCSF |

UCLA |

UCSD |

UCD |

UCI |

UCB |

UCR |

| Best Medical Schools – Research |

5 |

6 |

21 |

30 |

45 |

|

89 |

| Best Medical Schools – Primary Care |

3 |

5 |

30 |

9 |

74 |

|

|

| Best Nursing Schools – Masters |

18 |

20 |

|

46 |

87 |

|

|

| Best Graduate Public Health |

|

11 |

|

|

|

9 |

|

| Best Pharmacy Schools |

3 |

|

25 |

|

|

|

|

| Best Veterinary Medicine Schools |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

Note: USN&WR does not rank dental or optometry programs.

special educational initiatives: filling the gaps in underserved communities

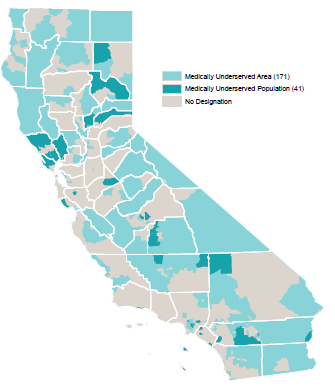

California is a vast state, and physician distribution is uneven. The state averages 72 primary care physicians per 100,000 population overall but some regions, such as the San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire, have much lower ratios, 39 and 35, respectively. All of UC Health’s schools emphasize public service and caring for the underserved. These programs include UC PRIME (Programs in Medical Education), UC Riverside, and the UCLA International Medical Graduate (IMG) program. (11.2.1.)

thinking boldly: California future health workforce commission

Despite the scale of UC Health's education and residency programs, the University cannot solve the state's looming health workforce shortage on its own. The California Future Health Workforce Commission was formed in 2017 and co-chaired by UC President Janet Napolitano and Lloyd Dean, CEO of Dignity Health. The Commission's 24 members included prominent health, policy, workforce development, and education leaders. In February 2019, the Commission issued its report and ten prioritized recommendations, including items directly related to UC Health’s educational mission.

- Expand and scale pipeline programs to recruit and prepare students from underrepresented and low-income backgrounds for health careers.

- Recruit and support college students, including community college students, from underrepresented regions and backgrounds to pursue health careers.

- Support scholarships for qualified students who pursue priority health professions and serve in underserved communities.

- Sustain and expand the Programs in Medical Education (PRIME) effort across UC campuses.

- Expand the number of primary care physician and psychiatry residency positions.

- Recruit and train students from rural areas and other underresourced communities to practice in community health centers in their home regions.

- Maximize the role of nurse practitioners as part of the care team to help fill gaps in primary care.

- Establish and scale a universal home care worker family of jobs with career ladders and training.

- Develop a psychiatric nurse practitioner program that recruits from and trains providers to serve in underserved rural and urban communities.

- Scale the engagement of community health workers, promotores (community health workers), and peer providers through certification, training, and reimbursement.

Medical Center residency programs — increasingly funded without medicare or Medi-cal support

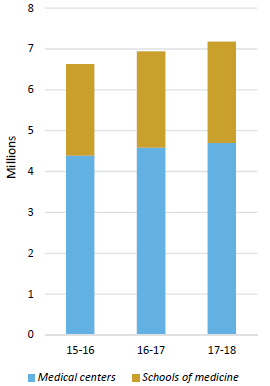

The interrelationship between UC Health’s educational and public service missions is evident in the residency programs at each medical center. Graduate Medical Education (GME), also known as residency programs, provide in-depth training in specialties of medicine after graduation from medical school. Participating in a residency program is required for a medical school graduate to become licensed to practice medicine independently. All of UC’s academic medical centers (AMCs) provide residency programs and fund an increasing number of them without traditional support from Medicare or Medicaid.

In the 1960s, Medicare began paying for a substantial portion of the cost of residency programs. In 1997, Congress limited the number of residencies Medicare would fund at established programs. This ‘residency cap’ has not been revised upward in more than 20 years, despite an increase nationally in the number of enrolled medical students and a growing, aging, and diversifying U.S. population that needs more practitioners.

In other parts of the country, GME programs also receive financial support through Medicaid, a program for low-income individuals that is administered by the state in accordance with federal guidelines. In California, Medicaid is known as Medi-Cal.

Unlike with Medicare, the federal government leaves it up to each state to determine if GME funding will be provided through its Medicaid program. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), 42 states and the District of Columbia make GME payments via their Medicaid programs. California is not one of them, despite having the largest number of teaching hospitals in the nation and the second-largest number of medical residents.

Recognizing the long-term impact of the residency bottleneck and the urgent emerging need for additional licensed providers, UC medical centers began absorbing costs for unfunded residency training slots.

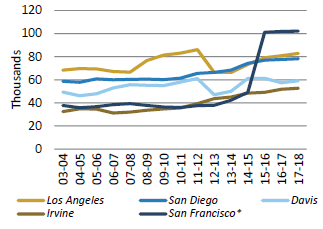

In AY18, UC Health trained 5,606 residents through UC-sponsored and long-standing UC-affiliated family medicine programs, representing about half of California’s total. This includes approximately 600 positions for which UC received no Medicare/Medi-Cal GME support, and covered roughly $60 million in unreimbursed costs.

The impact of residency extends far beyond the walls of hospitals operated by UC. Medical residents rotate among different sites of care as part of their exposure to a variety of patient populations and needs. Residents, working under the supervision of a licensed physician, provide care at county hospitals, Veterans Affairs hospitals, community hospitals, and specialty clinics.

boldly serving — improving access to care

Out of UC’s six health systems, five are AMCs operating 12 hospitals totaling 3,910 beds.

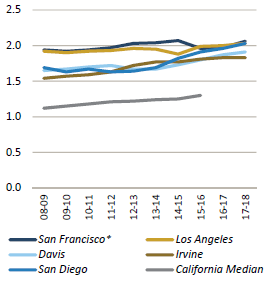

UC Health hospitals are destinations for some of the most critically ill patients in the state. One way to understand the health needs of hospitalized patients is by calculating the Case Mix Index (CMI). The CMI groups people together by primary and secondary diagnoses, and then factors in the number of procedures needed, patient ages and comorbidities to produce a score. As the number climbs above 1.0, it indicates increasingly poor health. The CMIs at most of California’s acute care hospitals range from 1.1 to 1.5. The CMIs at UC Health hospitals ranged from 1.83 to 2.06 in FY18 (11.4.1).

All across the state, each of UC Health’s academic medical centers has earned a place among U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Hospital” rankings, as shown in the table below:

| Best Hospitals - Nationally |

Best Hospitals - California |

| #6 UCSF |

#1 UCSF |

| #7 UCLA |

#2 UCLA |

| |

#5 UCD |

| |

#9 UCSD |

| |

#11 UCI |

Medi-Cal – the commitment to all Californians

Almost one in three Californians — 13.5 million people — have health insurance coverage through Medi-Cal.

UC Health values the significant role Medi-Cal plays in preserving and improving the health of the state. That’s why UC Health provides an outsized share of care for this population.

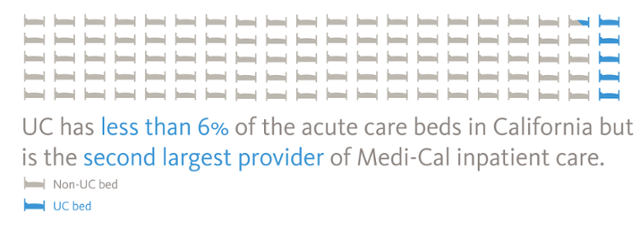

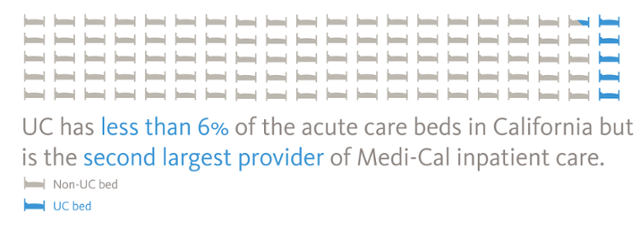

UC Health hospitals comprise less than six percent of the licensed general acute care staffed hospital beds in California, yet have become the second-largest provider of hospital inpatient days, as well as the second-largest provider of hospital outpatient visits for Medi-Cal beneficiaries.

Source: American Hospital Directory cites 74,925 non-federal, short-term, acute care staffed hospital beds in CA.

Over the years, California’s Medi-Cal program has undergone a substantial evolution away from a fee-for-service structure to six managed care models. Eighty-two percent of certified eligible enrollees are now in some form of managed Medi-Cal.

The state operates its Medi-Cal program under a variety of federal waivers, two of which are approaching renewal. California’s Section 1115 Medi-Cal 2020 waiver (expires December 31, 2020) provides substantial federal support to improve access to care and innovate with care delivery. A separate waiver, Section 1915(b) (expires July 1, 2020), enables counties to vary from standard Medicaid rules to arrange for specialty mental health services.

Medi-Cal became one of the primary sources of health coverage in the state due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The expansion of Medi-Cal in 2014 increased enrollment by nearly 60 percent. As Medi-Cal enrollment grew, so did its cost, although the initial impact on the state’s General Fund has been initially minimized because of the federal government’s cost-sharing formula, dedicated state taxes paid by managed care organizations and fees paid by hospitals, and the state tobacco tax increase (Prop 56). For 2018–2019, the total cost of Medi-Cal spending is anticipated to reach $98.5 billion, of which 21 percent comes from the state General Fund.

In the 2019–2020 Governor’s Budget Summary, Medi-Cal is the second-largest category of state spending after K–12 education. By 2020, ten percent of the costs for the ACA Medi-Cal expansion population will be borne by the state. This shift, along with uncertainty about the federal government’s overall approach to Medicaid financing and eligibility, may become a significant financial challenge to the state and all safety-net hospitals, including UC Health.

In FY18, UC Health provided an estimated $1.87 billion in undercompensated and uncompensated care to Medi-Cal, Medicare and uninsured patients. UC health funding — minimal direct support from the state's general fund

UC Health’s medical centers are self-supporting. Clinical operations at the five AMCs — UC Davis Health, UCSF Health, UC Irvine Health, UCLA Health, and UC San Diego Health — generate revenue through insurance reimbursements from governmental and commercial payers.

Systemwide, inpatient days are 36 percent Medi-Cal, 31 percent Medicare, and 32 percent commercial contracts, with approximately one percent uninsured or self-pay. This payer mix is challenging, as Medi-Cal reimbursements are estimated to cover 50–60 percent of the cost of care per patient, and Medicare 90 percent. Higher commercial insurance reimbursements help fill the funding gap, but those payers are increasingly resistant to a renewal cycle of rising rates.

The financial performance of the medical centers contributes significantly to the University’s overall budget. In FY18, the medical centers generated $12.2 billion in revenue and provided $531 million in health system support to the Schools of Medicine to fund operating activities, clinical research, faculty practice plans, and other programs.The future — strategic plan and 'systemness'

The leadership of UC Health recognizes the rapid pace of change occurring among health delivery systems and in higher education and training of future health professionals. As noted in presentations to the Health Services Committee of the Regents, UC Health, writ large, is challenged by a highly competitive environment characterized by declining reimbursement, rapid consolidation, unpredictable health policy, and growing market and payer expectations.

UC Health Division office strategic plan

In 2017, the UC Health division office developed a comprehensive, multiyear strategic plan to further enhance efficiencies and collaborations among its component medical centers, health professional schools, student health centers, and health benefit offerings to UC employees.

In 2018, the strategic plan was refreshed in conjunction with University President Janet Napolitano’s overall review of UCOP’s structure and the appointment of an advisory committee to provide recommendations regarding UC Health’s operations. The process led to financial and staffing improvements, as well as a refinement of strategic goals aligned with UC’s academic, research, and clinical care missions.

Among the most impactful changes to the plan are:

- A new subdivision will be created within the UC Health Operations Budget for all activities funded solely by the Health Systems. Resources within this new subdivision will be allowed to grow in alignment with this strategic plan and with annual approval.

- Communication will be strengthened between UC Health and the Board of Regents Health Services Committee, the Chancellors of the six schools with Health Systems, and UCOP’s Executive Budget Committee.

- UC Health oversight of the student medical centers will involve stakeholders from Student Affairs in UCOP’s Office of the Provost and representatives from the Student Health and Counselling Programs on the campuses.

Taken together, the strategic plan’s priorities reaffirm the UC Health Division Office as a means of connecting the health components of the University and acting as a catalyst for change. Integral to the plan is a recognition that the future requires collaboration across locations.

Systemness — Doing together what cannot be done alone

The world-class expertise at each campus — when connected to like-minded colleagues at other sites — holds great promise for Californians and people around the world. Some examples follow below.

$950 million and counting — Leveraging scale for value

One of the earliest systemwide collaborations is the Leveraging Scale for Value initiative (LSfV), which works on supply chain, revenue cycle, and information technology improvements. The cumulative financial benefit for this project is more than $180 million for FY 2015, more than $440 million thru FY 2016, $720 million thru FY 2017 and more than $950 million lifetime to date.

More than a dozen clinical and research collaborations

The ability to convene workgroups and organize initiatives across the health delivery enterprise is one way to accelerate clinical advancement and quality. These collaborations are a few examples of multicampus workstreams underway:

UC BRAID

UC Health Quality and Population Health Collaborative

UC Health Pharmacy Project Plan

UC Health Telemedicine Steering Committee

UC Chief Quality Officers Collaboration

UC Fetal Consortium

UC Quality and Safety Leads

UC Simulation Center Directors

UC Sepsis Leads

UC Primary Care Collaborative

UC Cancer Consortium

UC Cardiothoracic Surgery Collaboration

looking ahead: a dynamic, competitive environment — moving forward through uncertainty

Perhaps no other industry faces as much uncertainty right now as health care. Actions at the federal level are gradually reducing the number of people who have health insurance. Essential programs such as the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program are under review at federal and state levels, potentially scaling back its scope or redirecting badly needed funds away from safety-net hospitals. And hospitals that serve high numbers of Medi-Cal beneficiaries must continually defend funding for Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) and other supplemental payment programs.

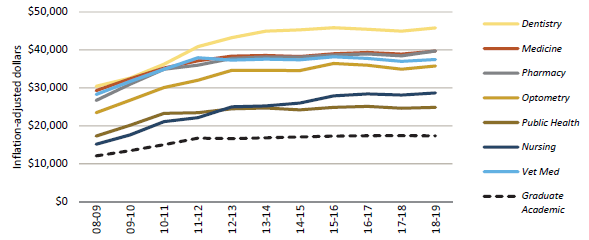

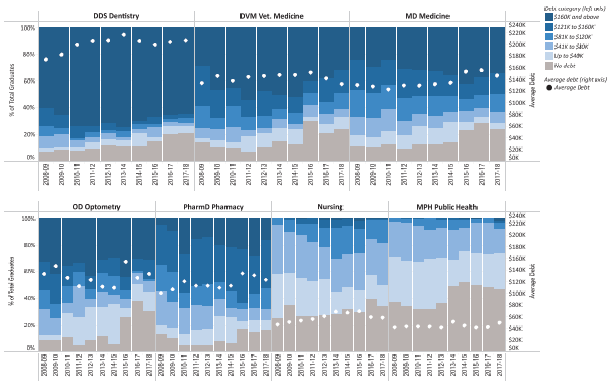

At the same time, California’s population continues to climb. Nearly 40 million people now call the Golden State their home. Yet our ability to meet the state’s growing health care needs are hampered. Federal caps on the number of Graduate Medical Education residencies and lack of funding through Medicare and Medi-Cal represent a significant bottleneck to growing the number of practicing physicians. Similarly, our ability to train tomorrow’s nurses, optometrists, dentists, pharmacists, public health professionals, and veterinarians are constrained by limited state support.

For the people of UC Health, our three missions continue in any environment: educate and train the next generation of health care providers, develop new treatments and cures, and provide a public service to the people of California.

For more information