chapter spotlight

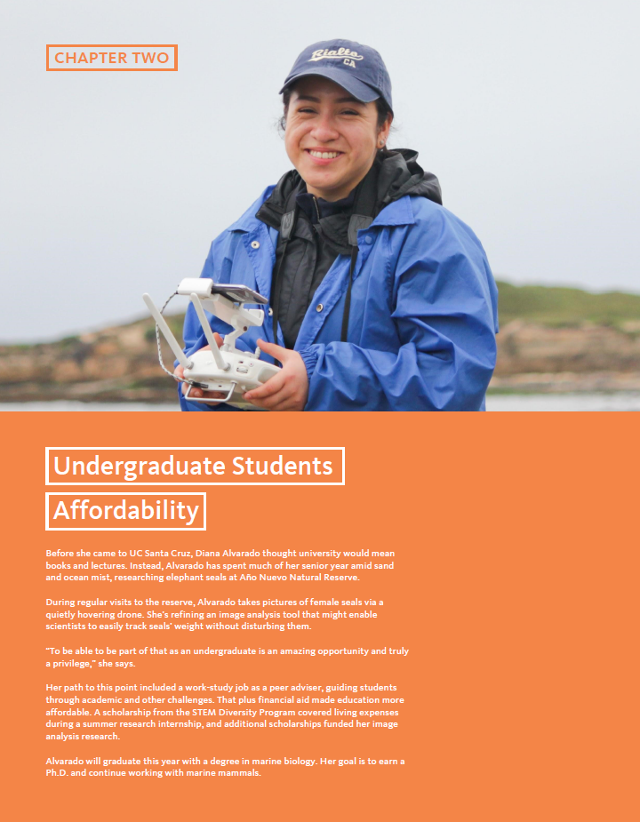

Before she came to UC Santa Cruz, Diana Alvarado thought university would mean books and lectures. Instead, Alvarado has spent much of her senior year amid sand and ocean mist, researching elephant seals at Año Nuevo Natural Reserve.

During regular visits to the reserve, Alvaradotakes pictures of female seals via a quietly hovering drone. She’s refining an image analysis tool that might enable scientists to easily track seals’ weight without disturbing them.

“To be able to be part of that as an undergraduate is an amazing opportunity and truly a privilege,” she says.

Her path to this point included a work-study job as a peer adviser, guiding students through academic and other challenges. That plus financial aid made education more affordable. A scholarship from the STEM Diversity Program covered living expenses during a summer research internship, and additional scholarships funded her image analysis research.

Alvarado will graduate this year with a degree in marine biology. Her goal is to earn a Ph.D. and continue working with marine mammals.

Goals

The goal of the University’s undergraduate financial aid program is to ensure that the University remains accessible to all academically eligible California students, regardless of their financial resources.

Affordability is among UC’s highest priorities. The University has maintained a strong record of enabling families from all income levels to finance a high-quality education, and it closely monitors the impact of its pricing decisions and financial aid programs.

Maintaining access

The total cost of attendance and the composition of undergraduates in terms of financial resources set the framework for what is required to provide adequate financial support.

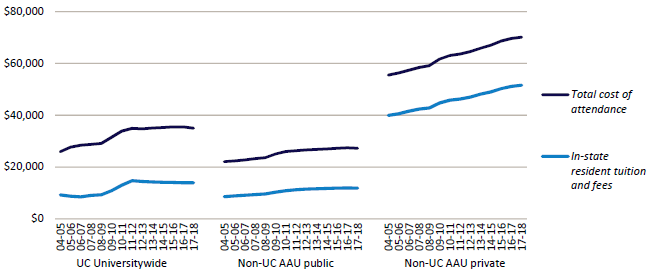

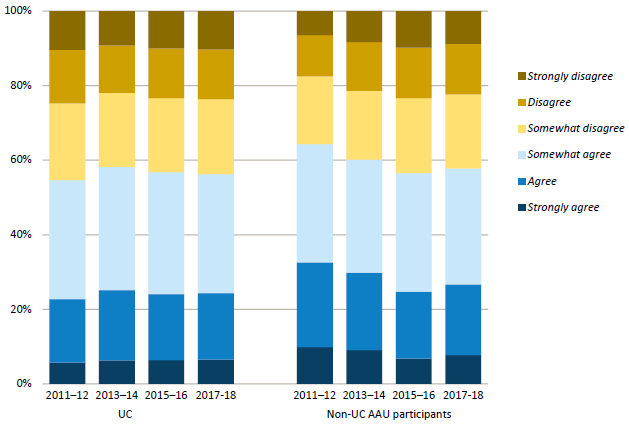

For in-state students who live on campus, the total annual cost of attendance, which comprises tuition and fees and other expenses (e.g., living and personal expenses, books and supplies, transportation, and health care), has remained relatively flat over the last several years at about $35,000. This figure compares to about $27,300 on average at other American Association of Universities (AAU) public institutions and around $70,000 for the AAU private institutions (2.1.1).

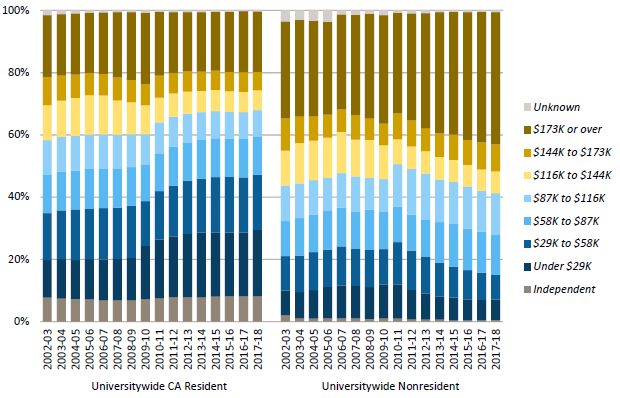

The income profile indicators demonstrate that the University remains accessible to low-income students. Between 2008–09 and 2017–18, the proportion of UC in-state undergraduates in the lowest income category increased from 14 percent to 21 percent, with offsetting declines among upper- and upper-middle-income families (2.2.2). These trends reflect both the manageability of UC’s net cost for low- and middle-income families, and the decline in the incomes of UC families since the 2009 economic recession.

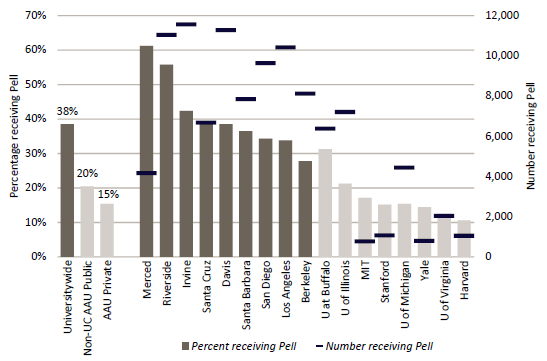

In fall 2018, 37 percent of all UC undergraduates received a Pell Grant, which is a federal grant for low-income students with family incomes typically under $50,000.

Financing a UC education

UC is able to provide access to students across the economic spectrum thanks to a progressive financial aid program that considers how much parents can afford; federal, state, and University gift aid or grants; and a manageable student “self-help” contribution from work or borrowing.

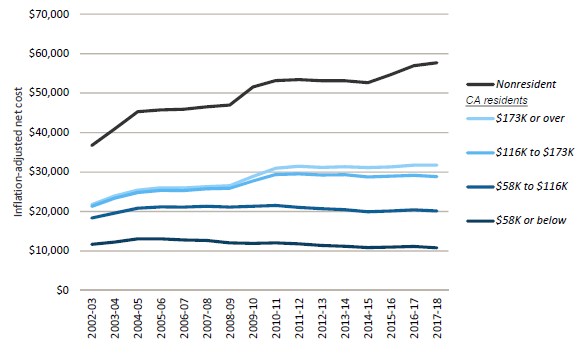

Gift aid dramatically reduces the net cost of attendance for students and enables those from low- and middle-income backgrounds to enroll in sizable numbers and proportions. The resulting inflation-adjusted net cost of attendance for in-state students from families in the lowest income bracket (less than $56,000) has declined or remained stable since 2004–05.

Federal and state governments provide critical support through the Pell Grant and Cal Grant Programs. In addition, UC’s commitment to affordability is evident in the University’s strong systemwide financial aid program. As a result of this robust institutional financial aid program, which combines support from different sources, 57 percent of California resident undergraduates paid no tuition in 2017–18. Furthermore, over two-thirds of UC’s own grant program helps students cover non-fee costs such as room, board, and book expenses.

Both UC and the State of California have made it a priority to provide financial support to undocumented students. Approximately 4,400 undocumented students received Cal Grants or need-based UC grants in 2017–18, totaling $94.9 million. The California Dream Loan Program continues to provide student loans to undocumented Assembly Bill (AB) 540 students at CSU and UC. The Legislature provided $3.5M in UC’s 2018–19 budget for the program, which has been matched by UC’s own funding of another $3.5M. Undocumented students who qualify for a waiver of nonresident supplemental tuition under AB 540 have been eligible for Cal Grants and UC grants since 2013 under the California Dream Act.

An undergraduate’s self-help requirement can be met through a combination of work and loans. UC relies on student surveys — including the UC Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES) and Cost of Attendance Survey — to measure how much students work. UCUES data show that over 50 percent of undergraduates do not work. Studies indicate that 20 hours of work per week is the threshold at which undergraduate academic performance may be adversely affected, and UC’s financial aid programs are structured to expect no more than 20 hours. Nevertheless, in the most recent UCUES survey (2018), ten percent of students reported working more than 20 hours per week, the same share as two years earlier.

For the academic year 2017–18, about 42 percent of California undergraduates relied on federal student loans to help finance their education, with loan amounts averaging $6,200. Parental borrowing under the federal PLUS program remained at about six percent, with the average PLUS loan amount at about $17,000 per year.

Since 2014–15, California’s Middle Class Scholarship program has provided a new source of gift assistance for students at UC and the California State University with household incomes of up to $164,000 who receive limited or no need-based financial aid. In 2017–18, UC students received $24.8 million in Middle Class Scholarship awards.

Addressing basic needs

Universities across the nation are attempting to address student basic needs. UC provides unprecedented access to low-income students and has prioritized efforts to address food and housing insecurity. Spring 2018 UCUES survey results show 47 percent experience low to very low food security (27 percent report very low food security) and four percent report being homeless. The UC Office of the President has partnered with UC Systemwide Basic Needs Committee members to share data collection efforts and findings with intersegmental groups, including our California State University and California Community College colleagues, and has presented survey results to the UC Board of Regents Special Committee on Basic Needs.

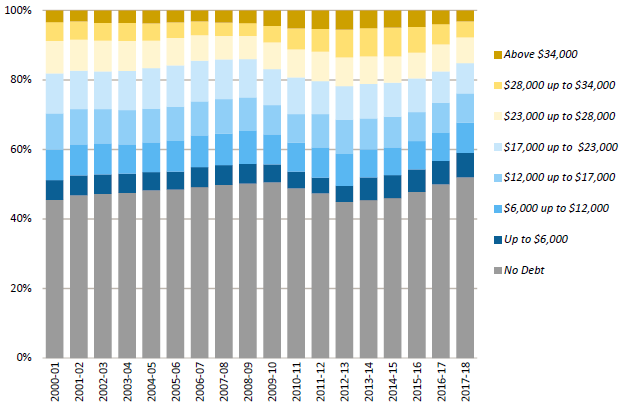

Limiting cumulative debt

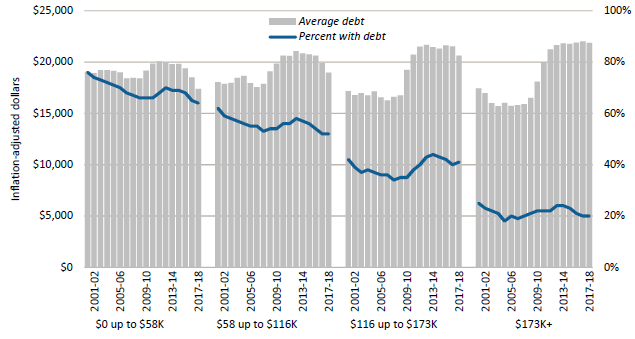

The proportion of undergraduates leaving with debt is lower than a decade ago. About 48 percent of the class of 2017–18 graduated with debt, with an average amount of $20,200. This translates into a monthly repayment amount of about $214 for ten years at a five percent annual interest rate. This level of debt is manageable, considering that a typical graduate who takes out loans earns about $3,300 a month within two years after graduation (2.3.2).

Comparison data show the 2016–17 cumulative debt for UC undergraduates was $21,100, compared to $27,293 for public four-year institutions and $32,810 for private nonprofit four-year institutions (2.3.4).

Looking forward

Both the Governor and State Legislature have proposed ideas for reforming and expanding the Cal Grant Program. Governor Newsom proposed increasing Cal Grant awards to students who are parenting young children, and this is currently under review. The State Legislature requested the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) to study opportunities for reform of the state’s Cal Grant Programs. Proposals now being considered include a wide variety of reforms, from eliminating requirements that disenfranchise nontraditional students, to accounting for the total cost of attendance in Cal Grant awards. University of California President Napolitano and California State University Chancellor White released a joint statement in November of 2018 outlining common policy priorities for Cal Grant Reform for the public university systems. Under the UC 2030 multiyear plan, UC’s goal is to increase timely graduation which would reduce student debt and the cost of education.

For more information