Chapter 12:

University Finances and Private Giving

Background and funding trends

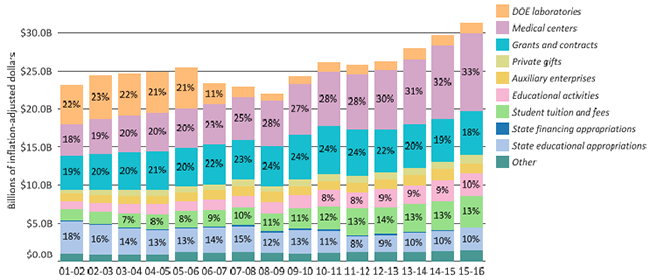

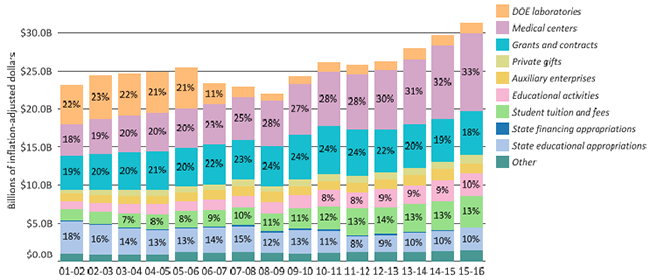

The University’s revenues, at about $31.3 billion in 2015–16, fund its core mission and a wide range of support activities. Prior to 2010–11, state funding was the largest single source of support for the education function of the University. Over the past ten years, state educational appropriations have fallen nearly $1 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars despite UC’s enrollment growth. State educational appropriations constituted only 10 percent of UC’s revenues in 2015–16 compared to 23 percent in 2001–02 (excluding DOE laboratories).

To offset declines in state funding, the University has sought to increase revenues from other sources, such as student tuition and fees, indirect cost recovery and private giving. The University also has moved to reduce operating costs and identify new sources of revenues. Chapter 13 identifies some of these cost savings. Even under optimistic assumptions, however, efficiency improvements and alternative revenue generation can meet only a portion of the projected needs.

What this means for students and families

Although the inflation-adjusted cost of educating a student at UC has dropped by 22 percent since 1990, the state’s share of this cost has fallen even more steeply, so students and their families now bear a larger share. Increases in student fees have not made up for the reductions in state support, thus total per-student expenditures have fallen.

Looking forward

Improvements in the California economy, combined with the November 2012 passage of Proposition 30 by California voters, have brought some stability to the state budget and thus to the UC budget.

The University has made comprehensive changes in the way funds flow. Historically, certain revenues were collected centrally and redistributed. Following consultation with campus leadership, nearly all campus-generated funds — tuition and fees, research indirect cost recovery, and patent and investment income — are retained by or returned to the source campus. The University has established a broad-based assessment on campus funds to support the Office of the President and systemwide initiatives. These changes — referred to as the Funding Streams Initiative — have simplified planning, improved transparency and motivated campuses to maximize revenue.

The University has fully implemented an initiative known as “Rebenching,” which distributes state funds on an equal per-weighted-student basis across the campuses and ensures that students are supported equally by the state regardless of campus.

Even with the stabilization of state support, UC faces financial challenges. The University has adopted measures designed to preserve the long-term viability of its pension plan while providing competitive post-employment benefits. As health care costs rise, UC will encounter mounting costs in providing coverage for its students, employees and retirees. The Affordable Care Act is having a profound effect on the finances of UC medical centers. While larger numbers of individuals with coverage are requesting health care services, certain reimbursements for Medicaid patients have been reduced.

Chronic shortfalls in priority areas — graduate student support, faculty salaries, the ratio of students to faculty, capital renewal and the need to upgrade outdated information systems — are major issues that will present financial challenges in the coming years.

For more information

Between 2001–02 and 2015–16, state educational appropriations decreased from 23 percent of UC revenues to 10 percent.

12.1.1 Revenues, by source, Universitywide, 2001–02 to 2015–16

Source: UC Revenue and Expense Trend Report

The steep decline in state educational appropriations as a proportion of UC’s total revenues over the past decade is a function of two trends: a long-term decline in state support; and an increase in revenues from other sources, such as medical centers, contracts and grants, and student tuition and fees.

State educational appropriations are for educational and other specific operating purposes, whereas state financing appropriations provide principal and interest payments for lease-purchase agreements. Funds from educational activities are derived primarily from medical professional fees.

Private gift funding shown in the chart above does not include gifts to UC foundations that are reported in the foundations’ audited financial statements. Private gifts made to the foundations are reported as gifts in the UC-wide financial statements when the gifts are transferred by the foundations to the University.

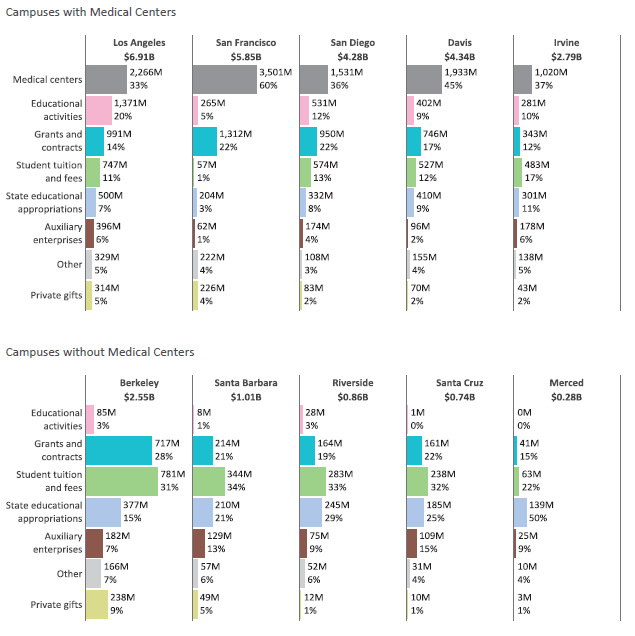

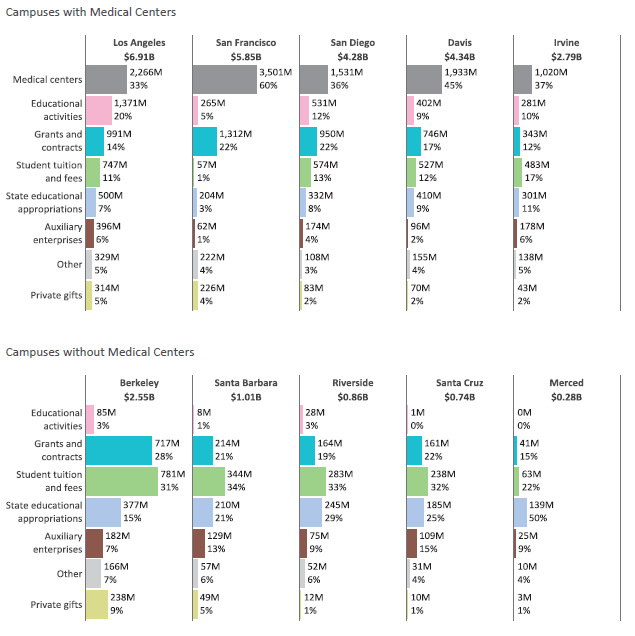

12.1.2 Revenues, by source, UC campuses, 2015–16

Additional years for campus revenues and expenditures are available on the UC Information Center.

Source: UC Revenue and Expense Trend Report1

1The Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco campuses operate medical schools and teaching hospitals. In addition to the funds associated with medical school and teaching hospital operations, these programs help campuses attract additional contract and grant revenue.

Virtually all gift funds (99 percent) are restricted by donors in how they may be used.

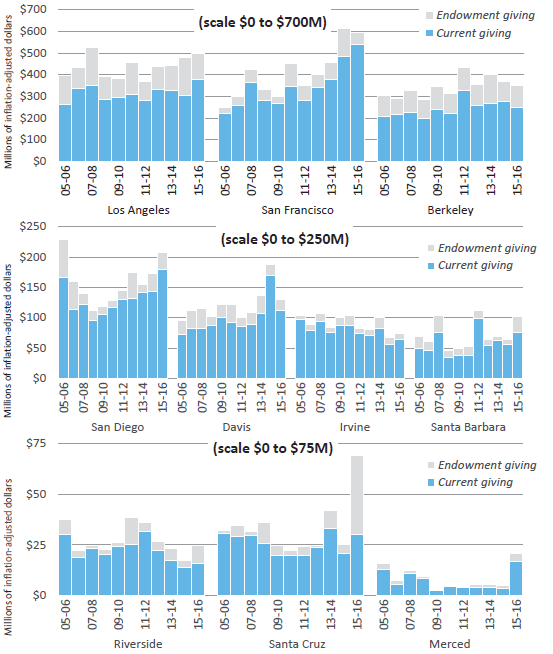

12.2.1 Current giving, by purpose, Universitywide, 2000–01 to 2015–16

Source: UC Institutional Advancement. Figures are adjusted for inflation.

In 2015–16, new gifts to the University totaled about $2.1 billion. Virtually all of these funds are restricted for specific purposes and are not available to support general operating costs. In addition, approximately $400 million was designated for endowment, so only the income/payout is available for expenditure.

The University is energetically pursuing increased philanthropic giving as a means to help address budget shortfalls and expand student financial aid.

Department support represents gifts in support of a specific department or academic division.

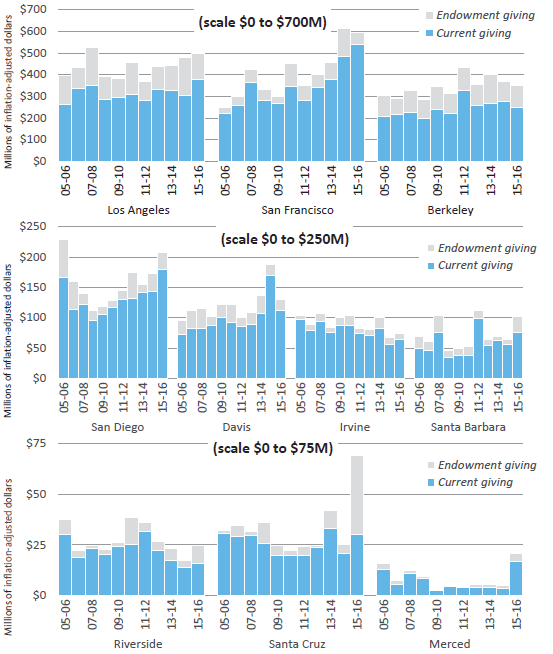

A campus’s ability to raise money is related to its age, number of alumni and presence of health science programs that attract nearly half of all private support at UC.

12.2.2 Total giving, by type, UC campuses, 2005–06 to 2015–16

Source: Council on Aid to Education (CAE). Current giving includes all giving except for endowment giving.

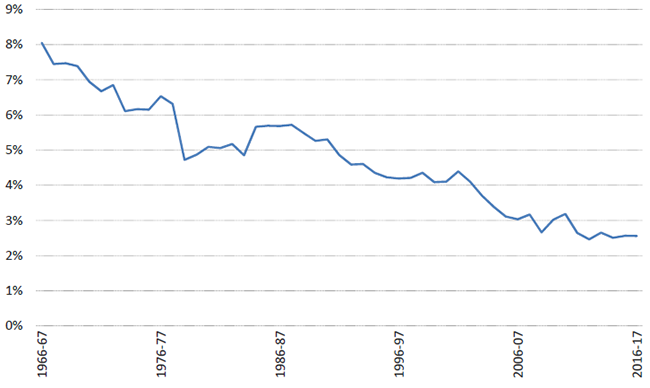

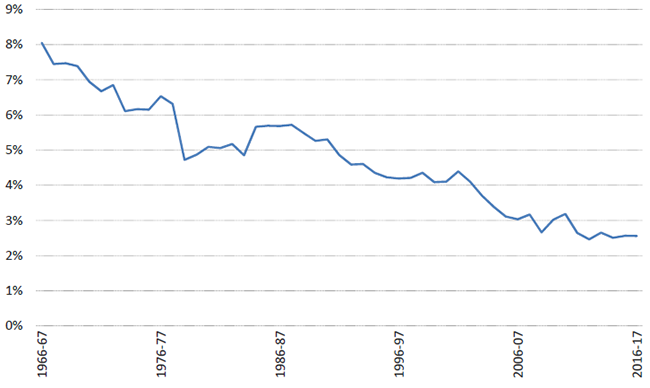

The University’s share of the state’s general fund dropped from 8.1 percent in

1966–67 to 2.6 percent in 2016–17.

12.3.1 UC share of the state budget, 1966–67 to 2016–17

Source: UC Budget Office

Historically, state funding has been the largest single source of support for the University’s core budget. Together with UC general funds1 and student fee revenue, state funding is used for faculty salaries and benefits, academic and administrative support, student services, facilities operation and maintenance, and student financial aid.

State support has fallen more than $1 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1990–91. To compensate, the University has raised student tuition and fees, but these increases have only partially compensated for the loss of state support (see indicator 12.5.1).

During the recent fiscal crisis, campuses laid off employees, deferred faculty hiring, cut academic programs, eliminated courses, increased class size and cut back vital student services such as library hours in order to address major funding shortfalls. State support is slowly being restored, although it has not yet caught up to pre-recession levels.

1 UC general funds are composed mostly of nonresident tuition revenue and indirect cost recovery from research grants and contracts.

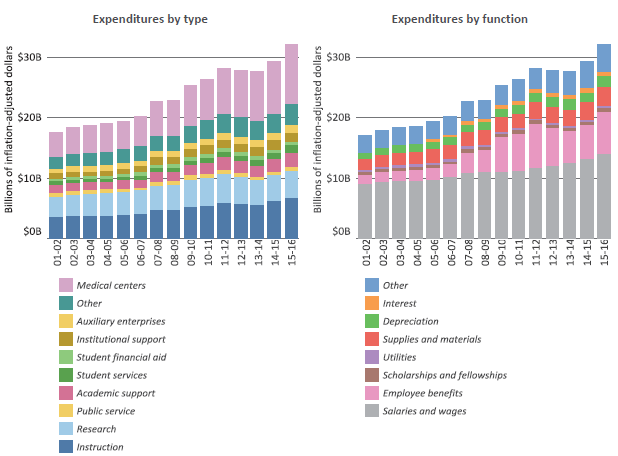

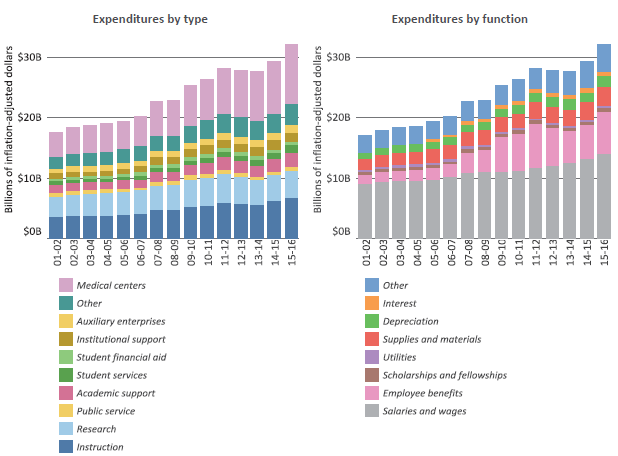

Personnel costs consistently account for over 60 percent of the University’s total expenditures.

12.4.1 Expenditures, by function, Universitywide, 2001–02 to 2015–16

Source: UC Revenue and Expense Trends Report and UC Corporate Financial System

1

Instruction, research and public service accounted for 37 percent of total expenditures during 2015–16, and medical centers accounted for 31 percent.

Higher education is a very labor-intensive enterprise. Personnel costs – salaries and wages, and employee benefits – consistently account for over 60 percent of the University’s total expenditures. The increase in employee benefit expenses is largely due to a resumption of contributions to UC’s retirement after a review of the retirement plan.

1 Inflation adjusted to 2014–15 dollars using CCPI-W. Medical centers refer to UC’s teaching hospitals; auxiliaries include student housing and dining, and parking garages; other expenses include interest, depreciation and other miscellaneous expenses. Support activities include student services, institutional support and academic support. Excludes Department of Energy laboratories, including the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

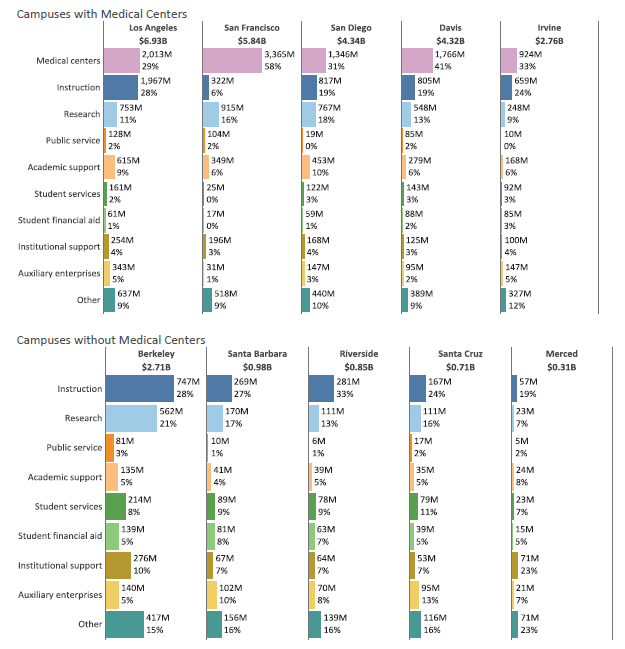

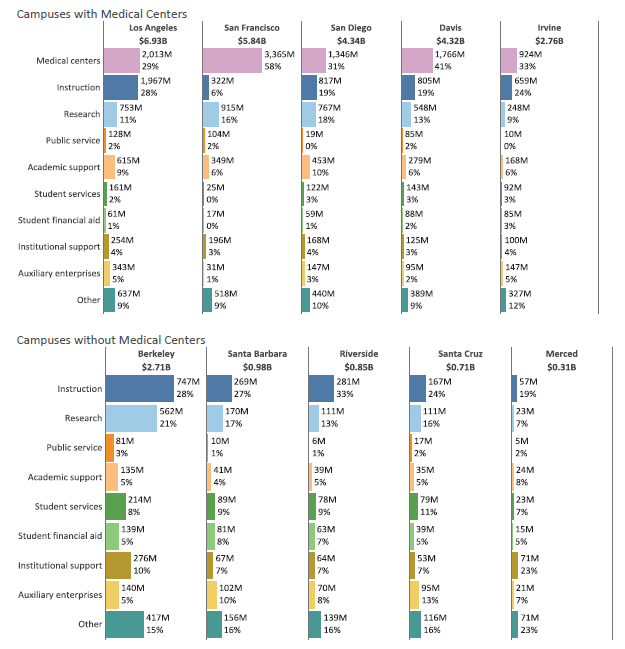

12.4.2 Expenditures, by function, UC campuses, 2015–16

Source: UC Audited Financial Statements1

Additional years for campus revenues and expenditures are available on the UC Information Center.

1Figures are in billions of inflation-adjusted 2014–15 dollars. The Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco campuses operate medical schools and teaching hospitals. In addition to the funds associated with medical school and teaching hospital operations, these programs help campuses attract additional contract and grant revenue.

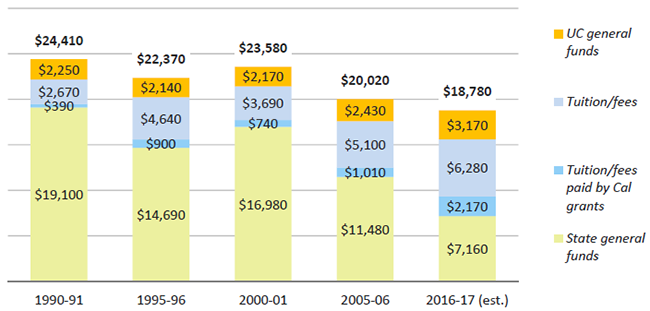

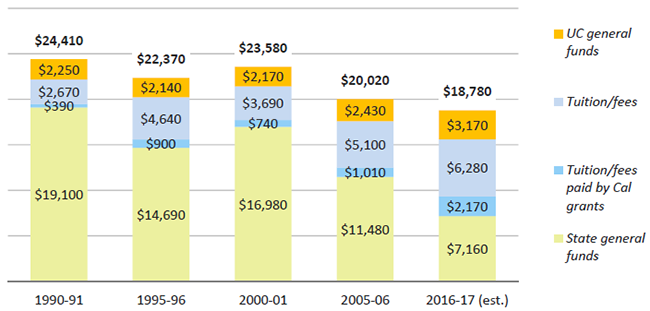

Since 1990–91, the total cost per student of a UC education has declined by 23 percent. However, students and their families have borne an ever-increasing share of that cost.

12.5.1 General campus per-student average expenditures for education, Universitywide, 1990–1991 to 2016–17, selected years

Source: UC Budget Office

Since 1990–91, average inflation-adjusted expenditures for educating UC students have declined 22 percent. During the same period, the state’s share of expenditures has fallen even more steeply, by 63 percent. The share of expenditures borne by students in the form of fees increased from 13 percent to 33 percent.

In other words, students and their families are bearing a growing proportion of the cost of their education. Increases in student fees have made up some, but not all, of the reductions in state support.