History

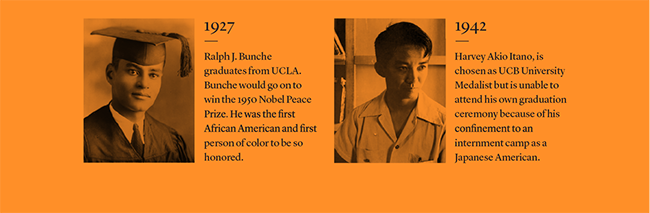

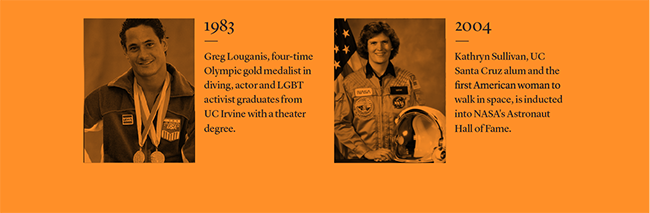

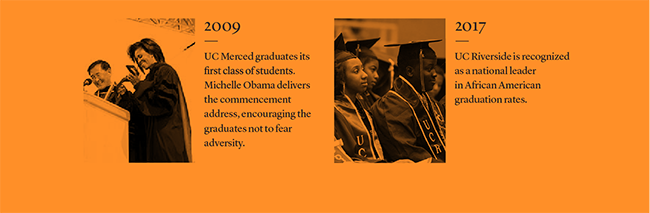

From the first twelve diplomas granted by the University of California in 1873 to UC Riverside being recognized as a national leader in African American graduation rates in 2017, the University has a storied history of undergraduate student success in academics, athletics, the arts and the sciences.

Those first twelve, known as the “12 Apostles,” were a testament to the breadth of impact the University would later have; among them came a U.S. congressman and California governor, a mayor, a bank president, two UC regents, a businessman, an attorney, an engineer, a math professor, a clergyman and a rancher.

Across the history of UC, there have been many notable undergraduates who have enjoyed great success since earning their UC degrees. Choosing just one from each campus to highlight here is a difficult task. Julia Morgan (UCB 1894), was the first woman architect licensed in California; Ralph Bunche (UCLA 1927), was the first person of color to win the Nobel Peace Prize; Robert Ballard (UCSB 1965), is an oceanographer who discovered the RMS Titanic; Kathryn Sullivan (UCSC 1973), was the first American woman to walk in space; Bruce Beutler (UCSD 1976), won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2011; Greg Louganis (UCI 1983), is an Olympic gold medal diver and LGBT activist; Tani Cantil-Sakauye (UCD 1984), is the Chief Justice of California; Steve Breen (UCR 1992), is an editorial cartoonist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner; Daniel Lobato (UCM 2013), is a pilot and first lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force, and benefactor behind the Lobato Endowed Scholarship Fund at UC Merced. Of course, there are many more stories of undergraduates with extraordinary success, but individuals alone do not tell the story of UC student success.

Goals

The University of California seeks to enable all entrants to complete their undergraduate degrees in a timely fashion and to ensure that their education prepares them to be the next generation of leaders for California, the nation and the world. President Napolitano seeks to increase the four-year freshman graduation rate from 66 percent (2013 cohort) to 70 percent by 2030. This would enable an additional 32,000 students to graduate over the next couple of decades.

Improving graduation rates

UC campuses have instituted a wide range of programs to promote the academic success of undergraduates, especially low-income and underrepresented students. These include academic preparation programs, individual student counseling and mentorship opportunities.

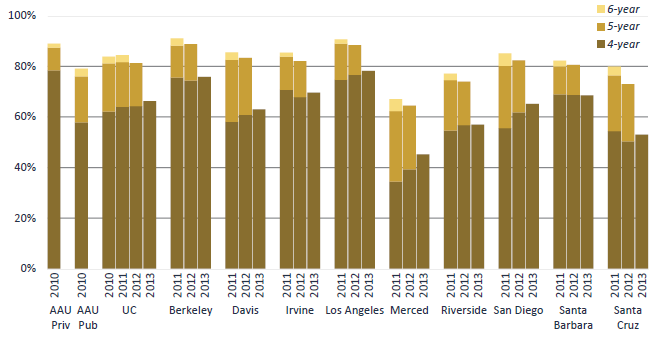

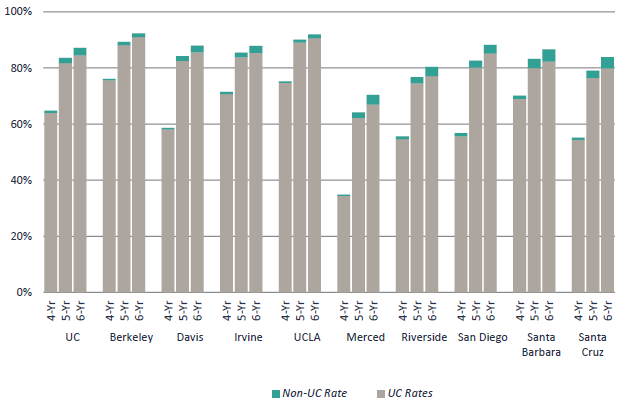

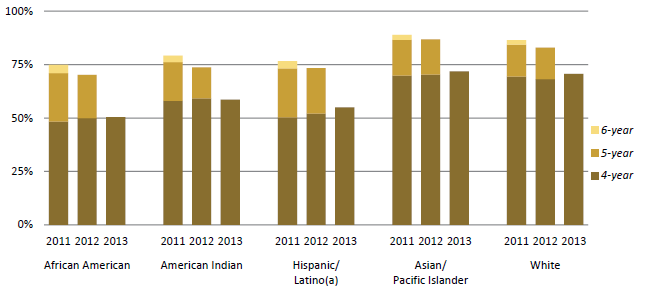

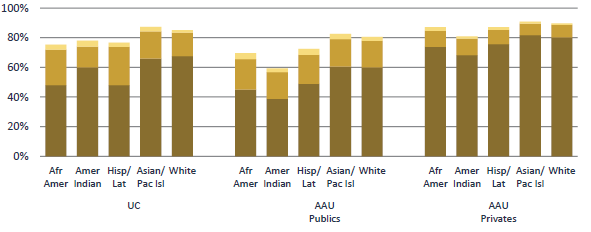

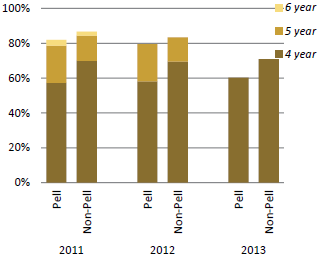

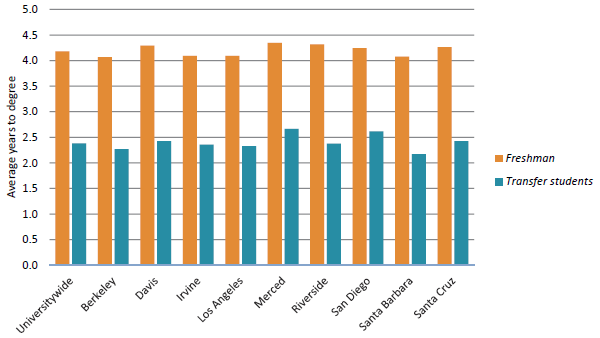

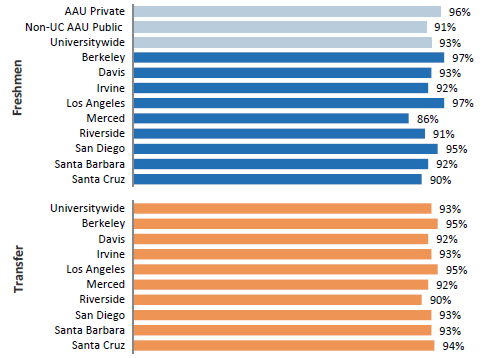

By traditional graduation rate measures, UC’s undergraduates are highly successful. UC’s four-year graduation rates for freshmen have risen significantly over the past 16 years — from 46 percent for the 1997 entering cohort to 66 percent for the 2013 cohort. The most recent six-year graduation rate, for the 2011 entering cohort, is 84 percent (3.1.1), which increases to 87 percent when including students who transfer to non-UC institutions (3.1.2) and still graduate within six years. In addition, time to degree has steadily improved, with freshman entrants now taking 4.2 years (3.1.8), on average, to graduate.

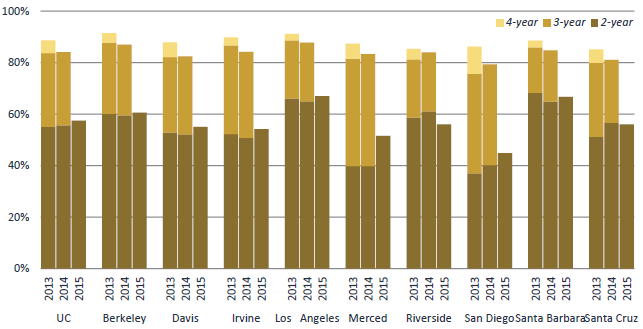

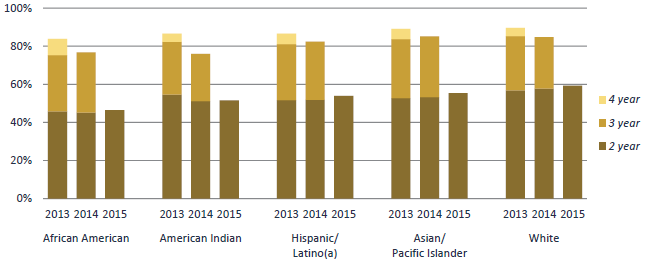

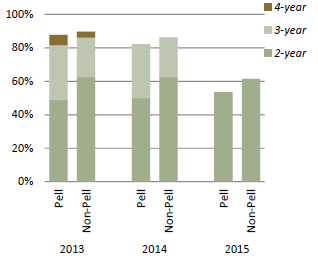

Transfer entrants have made similar gains, with two-year graduation rates increasing from 37 percent for the 1997 entering cohort to 57 percent for the 2015 cohort (3.1.3). The most recent four-year graduation rate for transfers (2013 entering cohort) is 89 percent and the average time to degree is 2.4 years (3.1.8).

Factors that affect graduation rates

As UC seeks to improve graduation rates, it is important to obtain a better understanding of factors that influence these rates. To assess this, logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the strength of the relationship between key factors (e.g., Pell status) and graduation rates.

The models pooled freshmen from the 2008, 2009 and 2010 entering cohorts. Multiple cohorts were analyzed to limit the possibility that results could be attributed to any one cohort. The models included variables used in higher education research, which have shown to affect graduation rates. Specifically, campus of enrollment, broad disciplinary area (i.e., Social Sciences, Arts & Humanities, STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and Other), pre-UC academic characteristics (e.g., SAT/ACT scores and high school GPA), UC academic performance (e.g., first-year GPA) along with demographic characteristics (e.g., first generation status, URG status and Pell status) were included.

Because factors such as high school GPA, first-year college GPA and SAT scores are measured on different scales and have different distributions, these variables were standardized in the analysis. The standardized units (one unit equals one standard deviation) represent a student’s performance relative to the population, allowing the comparison of the impact of a hypothetical change in one variable compared to the same relative change in another. After controlling for entry year, campus (e.g., UC Berkeley), and broad disciplinary area, evidence suggested that a one-unit increase in first-year UC GPA was associated with a 48 percent increase in the odds that a student would graduate within four years. A one-unit increase in high school GPA was associated with a 15 percent increase in the odds that a student would graduate within four years.

SAT/ACT test scores have less of a relationship with four-year graduation rates compared to high school GPA and first-year UC GPA. Specifically, a one-unit increase in SAT/ACT scores is associated with an eight percent increase in the odds that a student would graduate within four years.

While not presented in this chapter, results for six-year graduation rates were very similar to four-year graduation rates. Early academic success, specifically as it relates to first-year UC GPA, is a key factor for focus when seeking to improve graduation rates.

Academic preparation is only one factor that influences student success. Research has shown that engagement is also an important component. Engagement is often used to describe behaviors of students who are active learners, such as interacting with faculty members and contributing to class discussions. Research has also demonstrated that student engagement is correlated with the number of credits attempted and the number of credits earned, which are key factors for on-time degree completion.

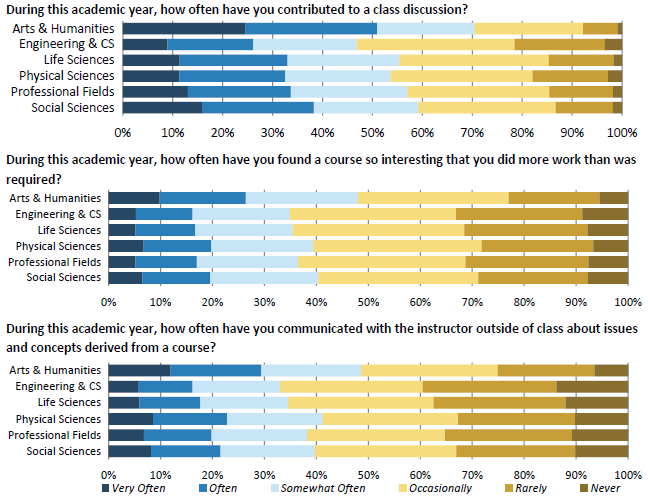

Evidence from the UC Undergraduate Student Experience Survey (UCUES), sent out biannually to all UC undergraduates, suggests that UC students overall are engaged with their education, although there is room for improvement. In 2016, more than half of students reported that they contributed to class discussions at least somewhat often, and more than a third went beyond required coursework somewhat often in a course they found interesting (3.3.2). About one-third of students at least somewhat often communicated with the instructor outside of class about issues and concepts derived from a course.

To determine if student engagement is related to academic performance, data from UCUES were merged with data on student outcomes. While the previous analyses focused on four-year graduation rates, evidence did not suggest that student engagement plays a significant factor in four-year graduation rates. This analysis examined the relationship between student engagement and first-year GPA, a key predictor of four-year graduation rates. Evidence suggested that contributing to a class discussion and doing more work than required in a class that one finds interesting were related to an increase in first-year UC GPA. This effect was found after controlling for entry cohort, survey administration year, campus of enrollment, student discipline, high school GPA, SAT/ACT scores, Pell status, first generation status and URG status. While not a major factor, student engagement was also shown to be related to student success, specifically as it relates to first-year GPA.

This chapter will present data on student success by demographic predictors. While the analyses above found that demographics are generally not strong predictors of success after controlling for academic predictors, it is important to note that the analyses above did not test how different factors interact. For instance, an underrepresented student may be more likely to attend a poorly performing high school. Being both low-income and first-generation will often affect a student more than just having one of these characteristics, even though they are closely correlated.

While the previous analysis mostly focused on pre-UC factors (e.g., high school GPA and SAT/ACT scores), the student experience at UC also plays a significant role in student success. Factors such as advising, financial support, and the availability of classes also contribute to student success. Recognizing the importance of these factors and early student succes for on-time graduation, UC campuses are making efforts to improve first-year student success. Many campuses offer first-year seminars to assist students with the transition from high school to UC. Seminars help students build a sense of community, understand the expectations of UC, engage with faculty and learn how to leverage campus resources. Campuses are also making advising mandatory for first-year students. Early advising helps students choose the right classes and obtain support. To help students understand the role of research in education, many UC campuses offer first-year students the opportunity to work on a research project with a faculty member. Systemwide, UC recently launched the First-Generation Faculty Initiative which connects first generation students to both faculty and staff mentors.

Undergraduate outcomes

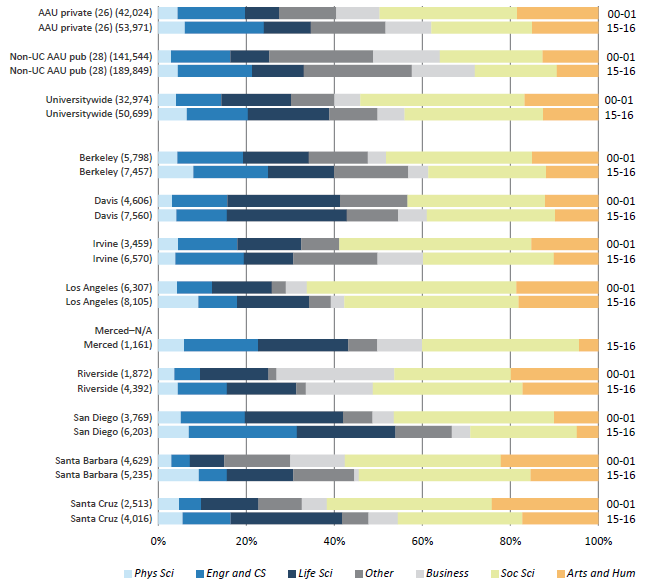

The number of undergraduate degrees awarded by UC over the past 15 years has grown by 55 percent, from about 32,700 degrees in 1999–2000 to about 50,700 degrees in 2015–16 (3.3.1). Increases in the size of the entering freshman class and improving graduation rates have contributed to this growth. More than one-third of the undergraduate degrees awarded by UC in 2015–16 were in STEM disciplines.

Four years after graduation, more than one-quarter of bachelor’s degree recipients have enrolled in graduate or professional programs.

UC alumni working in California surpass the typical earnings of other California bachelor’s degree recipients (aged 25 and over), by six years after graduation. The earnings trajectory of UC alumni increases rapidly — doubling what they were earning at two years after graduation by ten years after graduation, on average. Economic success is prevalent for all socioeconomic groups, including students whose families qualified for federal Pell Grants. Within seven years of graduation, the majority of Pell Grant recipients earn an average income higher than their parents’ combined incomes during the time those students attended UC (approximately $50,000).

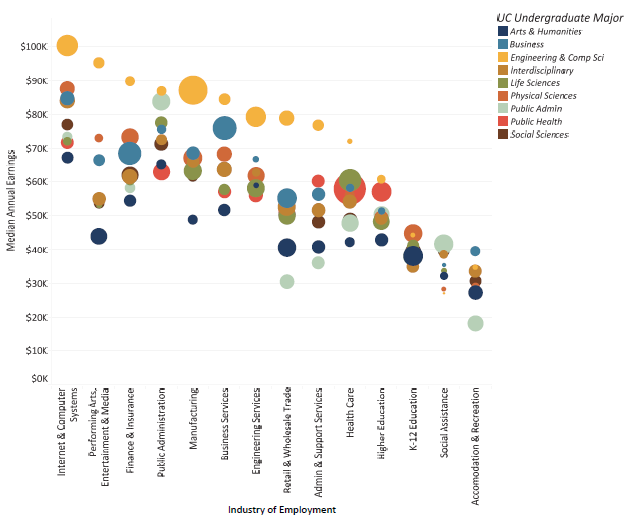

UC alumni are not only earning competitive salaries, more than half are working in key industries such as health care, K-12 education, finance & insurance, public administration, social assistance, higher education, engineering, and internet and computer systems. Many alumni work in industries that closely align with the major they chose. By ten years after graduation, 56 percent of engineering & computer science majors work in engineering, manufacturing, or internet and computer systems; 30 percent of life science majors work in health care and 34 percent of arts & humanities majors are working in K-12, higher education, or performing arts and entertainment.

Looking forward

Building on UC’s record of success, there are continued systemwide and campus efforts to improve undergraduate outcomes. Through the application of state funds, UC hopes to make additional progress in closing equity gaps in graduation rates between racial/ethnic groups.

For more information