Chapter 12:

Institutional Performance

Overview

UC requires significant resources and planning to support its instruction, research, and public service missions. The indicators in this chapter provide insight into the financial health of the University, the state of capital and space resources, and the environmental sustainability of campus operations.

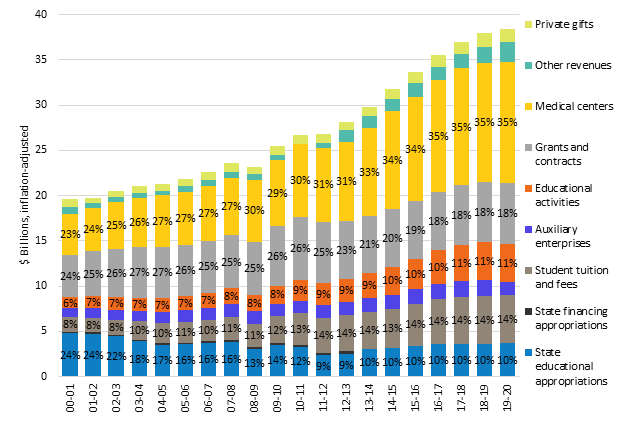

Financial trends The University’s revenues, totaling over $39.6 billion in 2019–20 (excluding Department of Energy laboratories), fund its core mission and a wide range of support activities. Over one-third comes from the five UC medical centers, which have collectively nearly doubled in size in the past decade. Contracts and grants, which help sustain the University’s research mission and reflect UC’s preeminence in research, are the next largest source of funds.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the final quarter of the 2019–20 fiscal year resulted in large revenue losses across various areas of the University. Shutdowns or drastic reductions in services such as nonessential patient care, housing and dining, and other auxiliary functions, including student refunds for cancelled contracts, resulted in revenue losses of about $1.5 billion as of July 31, 2020. These losses were partially offset by about $620 million in federal funding to the University by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020 (“CARES Act”), which was also intended to help with other costs associated with the pandemic such as facilities cleaning, COVID patient care, and remote instruction. An additional $130 million of CARES Act funding received by the University was restricted for direct student financial support.

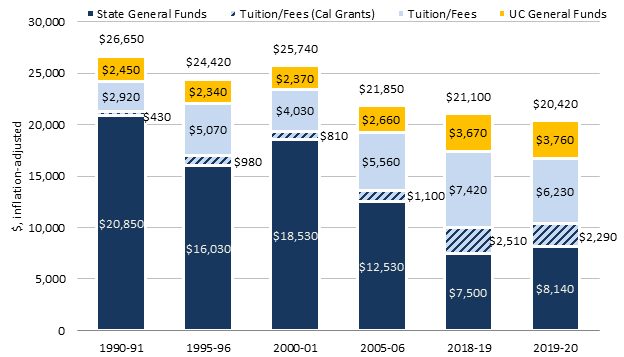

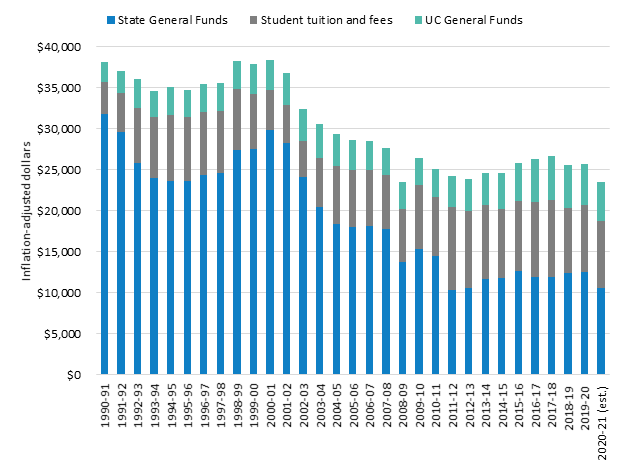

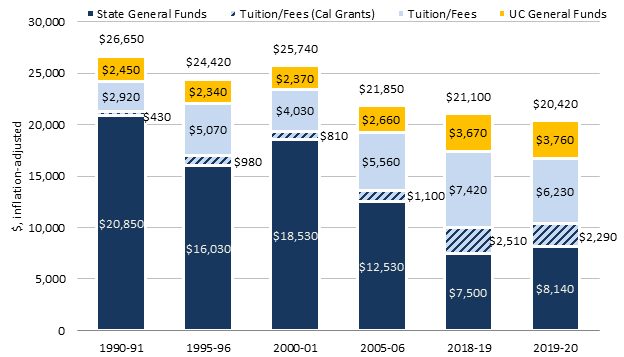

State General Funds, tuition and fees, and UC General Funds make up the core revenues for the University’s instructional mission. State funds were historically the largest single source of support for instruction; however, cuts in State funding over the past two decades reduced this resource. State educational appropriations are less today in inflation-adjusted dollars than they were in 2006–07 and over $1 billion less than what they were in 2000–01, despite substantial enrollment growth. In 2000–01, State funding for UC, including Cal Grants, contributed $18,530 per student —– 72% of the total cost. In 2019–20, the State share declined to $8,140, or 40% of the total cost. From 2000–01 to 2010–11, systemwide tuition and fees were increased to offset the impacts of reduced funding from the State, though financial aid increases made up for those increases for many UC students. In-state tuition at UC has remained flat for eight of the last nine years. Under these circumstances, the importance of alternative sources of funding, such as Nonresident Supplemental Tuition, has increased. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, improvements in the California economy since 2012, combined with the passage of Proposition 30, had brought some stability to the State budget and thus to the University’s core budget. Modest increases in State support during times of fiscal stability have not been enough to both fully restore prior funding levels and keep pace with enrollment growth. In addition, the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic toward the end of the 2019–20 fiscal year resulted in State budget uncertainty for 2020–21 and 2021–22.

As core revenues per student have declined from $38,000 in 1990–91 to $25,700 in 2019–20, driven primarily by decreases in State General Funds on a per-student basis, the University has sought to increase revenues from other sources. Gift funds have become increasingly important. Private giving has increased; however, over 99 percent is restricted. Gift support tends to be for research, departmental support, and capital projects. The small amounts for instruction and student support cannot offset needs created by enrollment growth that has outpaced proportional growth in core revenues. Private giving varies significantly by campus and relates to the campus’ age, number of alumni, and the presence of health science programs.

As is typical for universities, salaries and benefits for academic and support staff are the largest areas of expenditures. Although the inflation-adjusted expenditures for educating a student at UC have dropped by 23 percent since 1990, reflecting both operational efficiencies and reductions in available resources, the State’s share of this cost has fallen even more steeply. Consequently, students and their families now contribute a larger share through tuition and fees.

Chronic shortfalls in priority areas — graduate student support, faculty salaries, the ratio of students to faculty, capital renewal, the need to upgrade outdated information systems, and a focus on sustainability — present ongoing financial challenges.

Capital program and funding

The University maintains approximately 6,000 buildings enclosing 146 million gross square feet on approximately 30,000 acres across its ten campuses, five medical centers, nine agricultural research and extension centers, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. With such a substantial infrastructure, the University strives to be a good steward of the capital resources entrusted to its care.

UC’s capital program is funded by a combination of State and non-State funds. Historically, the majority of UC’s core academic capital projects were funded by the State. With State funds playing a declining role over the past decade, the University has been forced to rely on other resources. In the past decade, non-State funds, including external financing that utilizes non-State sources to service the debt, have accounted for 80 percent of UC’s capital program funding.

During fiscal year 2019–20, UC approved capital project budgets totaling $2.6 billion. Approximately two-thirds of the cost was met through debt financing, including external financing supported by State General Funds. The remaining capital projects were funded by non-State sources, including public-private partnerships, which have become a growing part of UC’s capital projects strategy, particularly for student housing.

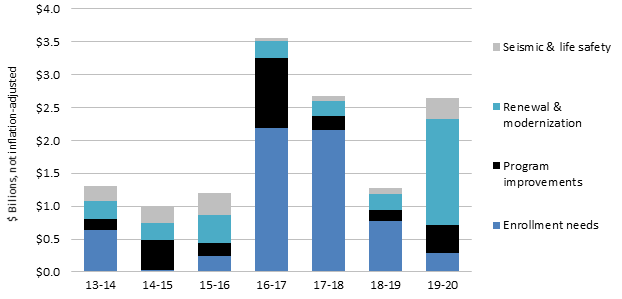

In 2015–16 and before, most capital projects were aimed at growing core academic programs and replacing aging facilities. In more recent years (2016–17 onward), there has been an increase in projects that address enrollment growth and program improvements. The majority of 2019–20 capital projects addressed renewal and modernization of the aging plant as well as seismic improvements in recognition that close to half of UC’s facilities are more than 35 years old.

UC sustainability

The University of California is a national leader in sustainability. UC’s sustainability commitment began in 2003 with a Regental action that led to the adoption of a Presidential Policy on Green Building Design and Clean Energy Standards in 2004. Demonstrating the University’s commitment to wise stewardship of its resources and the environment, the Policy has since expanded to include multiple areas of focus: Climate Protection, Green Building Design, Clean Energy, Sustainable Transportation, Sustainable Building Operations, Zero Waste, Sustainable Procurement, Sustainable Food Service, Water, and Sustainability in University of California Health. The University’s Sustainable Practices Policy was updated again in 2020.

The University committed to systemwide climate action leadership in 2007, when all ten Chancellors signed the American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment to achieve carbon neutrality as soon as possible. Furthering this leadership, in November 2013, UC announced an initiative to achieve carbon neutrality by 2025. This initiative will make UC the first major research university system to achieve carbon neutrality. Most recently, UC Merced became the first public research university in the country to achieve carbon neutrality.

The University’s Carbon Neutrality Initiative has advanced the University’s work on climate and carbon neutrality research and education, and furthers its leadership in sustainable business practices. Even as the campuses expand, overall greenhouse gas emissions have continued to drop due to improvements in energy efficiency, developing new sources of renewable energy, and enacting a range of related strategies to cut carbon emissions. For example, the University’s Clean Power Program is providing 100 percent clean electricity to eight campuses and three medical centers that are eligible to select an alternative energy provider. The Clean Power Program supplies approximately 26 percent of the University’s electricity use from off-campus sources. UC now generates more on-site renewable energy than any other university in the country and has over 100 renewable energy projects across the system. The University also funded 35 students with Carbon Neutrality Initiative Fellowships during the 2019–20 school year to work on projects supporting UC’s carbon neutrality goal.

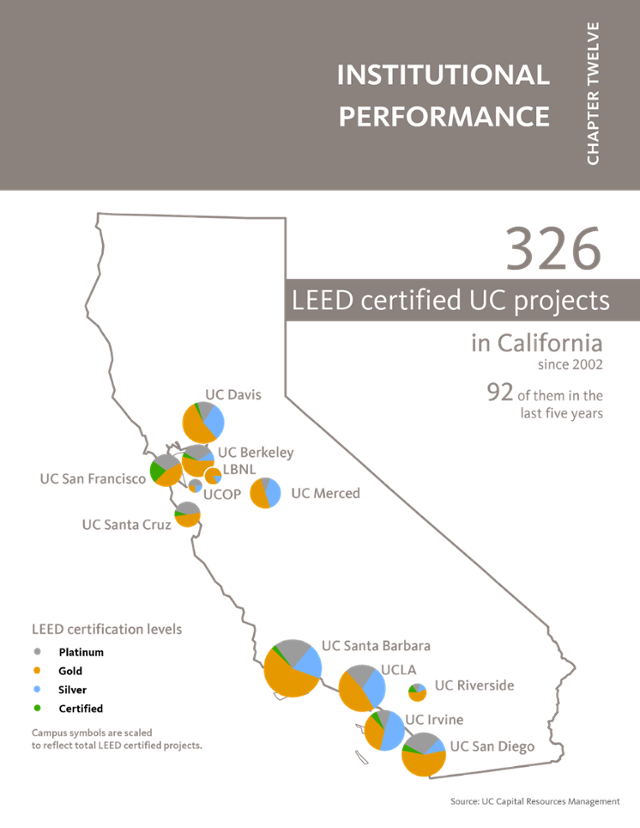

Upfront investments in energy efficiency are often costly, but energy efficiency projects across the system have so far netted over $316 million in cumulative avoided utility costs since 2005. Moreover, UC’s policy requiring that all new construction projects and major renovations receive LEED® (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification helps assure that campus growth does not increase energy costs and climate pollution as much as it would otherwise. As of 2020, UC has 352 LEED certifications, the most of any higher education institution in the country. In addition to LEED and energy efficiency requirements, starting in 2019, new buildings are required to take advantage of the University’s access to carbon-free electricity and not use fossil-fuel combustion for space and water heating except under special circumstances.

Additionally, UC’s fleet continues to move toward zero-emission vehicles. Systemwide, nearly 60 percent of all new light-duty fleet vehicles purchased in fiscal year 2019–20 were battery-electric, plug-in hybrid, or gasoline-hybrid. There are over 1,300 electric vehicle charging stations throughout the UC system.

For more information

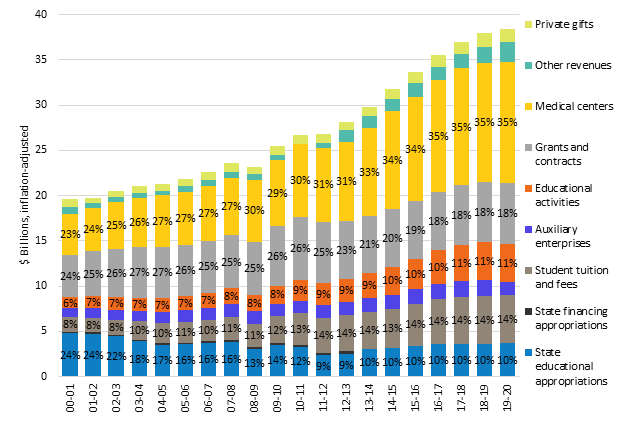

Over time, UC's varied sources of revenue have grown at different rates.

12.1.1 Revenues by source, Universitywide, 2000–01 to 2019-20

Source: UC Revenues and Expense Trend Report. Amounts do not include Department of Energy Laboratories.

Two major trends are reflected in the University’s revenue sources over time. First, revenues associated with the University’s medical centers and related activities have grown substantially since 2000–01. Medical center revenues now represent 35 percent of all UC revenues. On top of this category, a significant portion of revenues shown as “Educational activities” above is also related to health services.

Second, among the University’s core fund revenues, State appropriations now contribute less to the University’s operating budget than student tuition and fees. In 2019–20, State General Funds comprised 40 percent of UC’s core fund budget, while student tuition and fees comprised 42 percent.

Historically, State funding had been the largest single source of support for the University’s core budget. State support has declined from 87 percent of core funds in 1980–81 to 42% in 2019–20.

The COVID-19 pandemic further complicated the University’s revenue sources. In addition to new State budget cuts driven by the pandemic-related recession, there were significant impacts to medical centers and auxiliary enterprises in particular, over the final four months of the 2019–20 fiscal year. These revenue losses were partially offset by one-time federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020 (“CARES Act”).

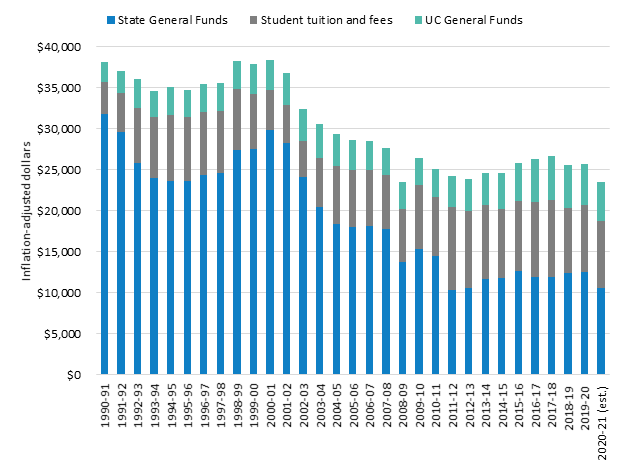

Since 2000–01, available core revenues per student have declined by 35 percent.

12.1.2 Per-student average inflation-adjusted core revenues, Universitywide, 2000–01 to 2019-20

Source: UC Budget Office

Since 2000–01, average inflation-adjusted revenues per student have declined 35 percent. During the same period, the State General Fund portion has fallen even more steeply, by 58 percent.

In some years, the University increased student tuition and fee levels to partly offset the long-term decline in State support. Financial aid increases have covered some or all of these cost increases for families with financial need. These increases in student fee revenue have not, however, fully offset the reduction in State funding per student.

UC General Funds are composed mostly of Nonresident Supplemental Tuition Revenue and indirect cost recovery from research contracts and grants.

Overall, decreases in available core revenues per student have put downward pressure on spending per student, as seen in indicator 12.1.5. Ultimately, this pullback may affect the quality of instruction and the student experience.

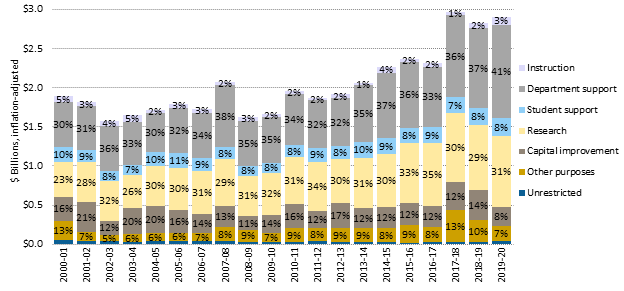

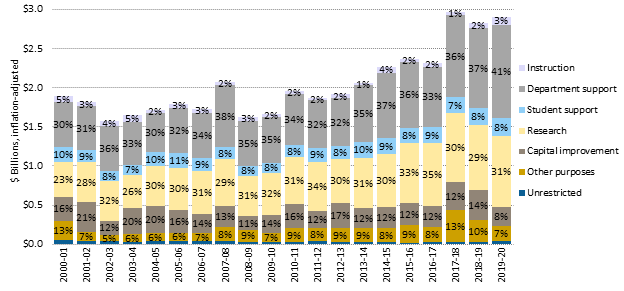

Virtually all gift funds (99 percent) are restricted by donors in how they may be used.

12.1.3 Current giving by purpose, Universitywide, 2000–01 to 2019-20

Source: UC Institutional Advancement

The University is energetically pursuing increased philanthropic giving as a means to help address budget shortfalls and expand student financial aid. Philanthropic support has been key to supporting the University, particularly through the challenging impacts of COVID-19.

In 2019–20, new gifts to the University totaled over $2.9 billion. Virtually all of these funds are restricted for specific purposes and are not available to support general operating costs. In addition, approximately $619 million was designated for endowment, so only the income/payout is available for expenditure. Gifts designated for department support are only eligible for use by a specific department or academic division.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, campuses received gifts to support remote learning resources, critical student financial needs, procurement of protective equipment, and expansion of infection testing.

The University’s remarkable achievement in obtaining private funding in recent years — even during state, national, and global economic downturns — is a testament to UC’s distinction as a leader among the nation’s public colleges and universities in generating philanthropic funds. These gifts reflect the high regard in which the University is held by its alumni, corporations, foundations, and other supporters.

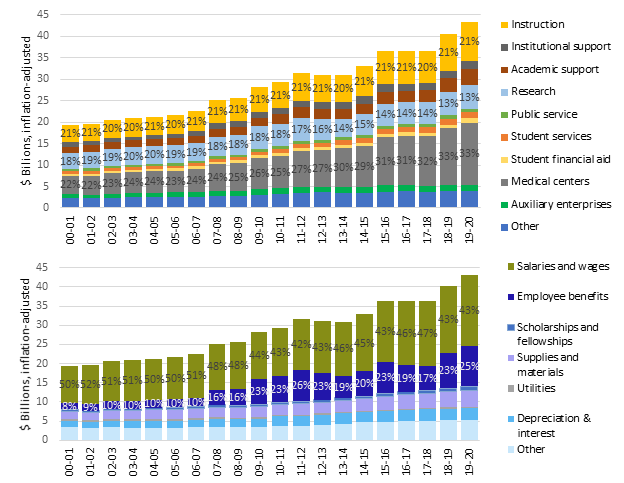

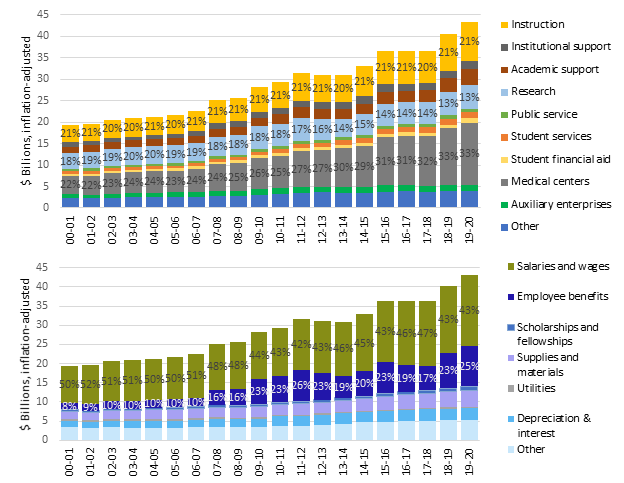

Personnel costs and medical centers are an increasing portion of UC expenditures.

12.1.4 Expenditures by function and type, Universitywide, 2000–01 to 2019-20

Source: UC Revenue and Expense Trends Report. Dollars are inflation-adjusted dollars using CCPI-W. Amounts do not include Department of Energy Laboratories.

When viewed by function, the combination of instruction, research, and public service accounted for 36 percent of total expenditures during 2019–20, while medical centers (UC’s teaching hospitals) accounted for 33 percent. Other expenses by function include interest, depreciation, and miscellaneous expenditures.

Looking at expenditures by type, about 68 percent are dedicated to personnel costs, since higher education, health care delivery, and research are inherently labor-intensive enterprises. Salary costs have increased both due to higher average salaries and increased full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, particularly at the medical centers. These increases also affect employee benefits; however, benefit costs also fluctuate due to variations in investment returns on the pension and the discount rate for retiree health.

In the final few months of the 2019–20 fiscal year, the University spent an additional $255 million in costs related to treating COVID-19 patients, transition to remote instruction, and facilities cleaning. These cost impacts will likely continue through the 2020–21 fiscal year.

Since 1990–91, total instructional expenditures per UC student have declined by 21 percent, yet students and their families bear a greater share of that cost.

12.1.5 Average general campus core fund expenditures for instruction per student, 1990–91 to 2019-20

Source: UC Budget Office, inflation-adjusted amounts

Since 1990–91, average expenditures for instruction per student from core funds have declined by 23 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars. Of this amount, the share provided by State support for the University’s budget declined from 78 percent in 1990–91 to only 40 percent of the total in 2019–20. In contrast, the contribution from tuition and fees has increased from 13 percent to 42 percent during the same period.

The State’s Cal Grant program has covered tuition and fee increases for many California resident undergraduate students. However, even after taking Cal Grants into account, State funding covered only 51 percent of instructional expenditures from core funds in 2019–20 compared to 80 percent in 1990–91.

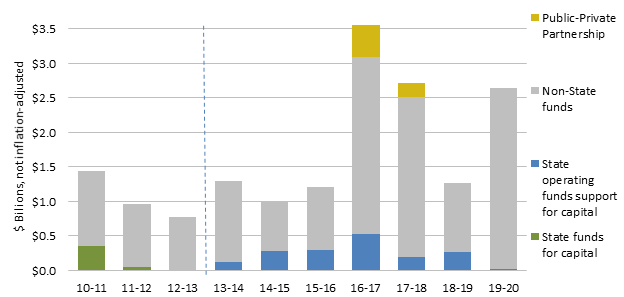

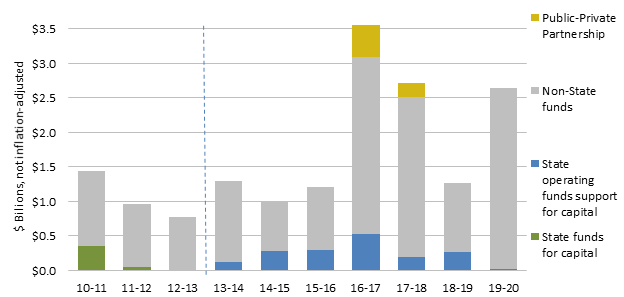

The majority of UC’s capital project funding over the last ten years continues to be derived from non-State fund sources. Starting in 2013–14, changes to the California Education Code allowed UC to direct a portion of its existing State operating funds support to capital.

12.2.1 Sources of capital project funding by year of approval, Universitywide, 2010–11 to 2019–20

Source: UC Capital Asset Strategies

The University’s capital program is driven by the campuses’ and medical centers’ strategic plans. UC’s capital program is funded by a combination of State and non-State funds. The nature of State funds has changed in recent years.

As illustrated in indicator 12.2.1, the dominant source of capital is non-State resources. Public-Private Partnerships are not included in the 2018–19 totals. A GO bond was placed on the March 2020 ballot but voters did not pass it.

Legislation in 2013–14 and 2018–19 enacted a change in how UC could fund its debt service, availability payments, and capital outlay expenditures. Instead of receiving dedicated capital funding from the State, UC can direct a portion of its State General Fund appropriations to fund debt service for State-eligible capital projects. The portion of State General Funds directed to capital does not represent new State funding and is made up of funds that are redirected from operations to support capital.

State funds were historically the primary source of funding for core academic facilities and seismic compliance for acute care hospitals. However, due to the elimination of specific State appropriations, some needs have been financed by the University. Non-State sources fund most of UC's State-eligible capital needs and all self-supporting enterprises, such as housing, parking, athletics, and medical centers. To the extent that non-State funds are used to support core academic capital needs, less funding is available to support other high-priority needs such as deferred maintenance, seismic, and enrollment growth.

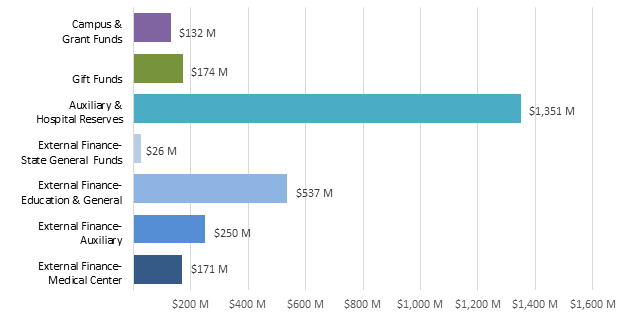

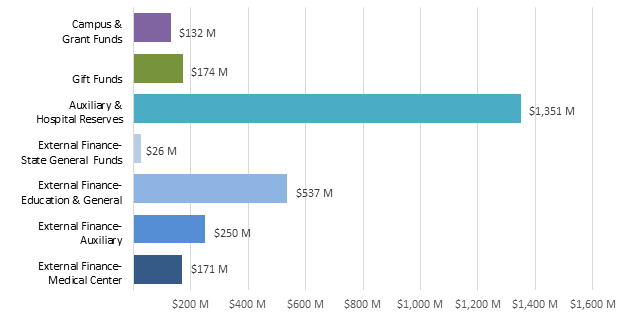

The 2019–20 capital project program is heavily supported by external financing.

12.2.2 Sources of capital spending detail, Universitywide, Project budgets approved in 2019-20

Source: UC Capital Asset Strategies

The University and each campus carefully consider how to deploy resources to optimize the benefits to academic programs and the University’s mission as a whole.

With State funding playing a declining role in the University’s capital program over the past decade, the University has relied on other means to fund capital projects. As noted in indicator 12.2.2, approximately one percent of capital funding for the 2019–20 capital program utilized external financing supported by State General Funds that could have been used to support operations.

Campuses also redirect non-State funds to projects that otherwise would have been funded with State resources.

External financing continues to play an important role in funding capital needs. About 36 percent of capital project funding in 2019–20 came from non-State supported external financing. The non-State financing supports student housing projects and research projects related to program improvements in the sciences as well as medical centers.

The remainder of UC’s capital program is funded by gift funds, campus funds, and other non-State sources. These campus funds are derived from a variety of sources, including indirect cost recovery and investment earnings.

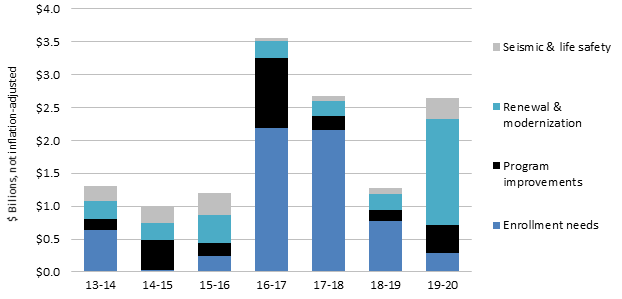

The majority of capital funds approved for expenditure in 2019–20 supported projects addressing growth in enrollment and renovation or replacement of aging facilities.

12.2.3 Types of capital projects, based on budgets approved by year, Universitywide, 2013–14 to 2019–20

Source: UC Capital Asset Strategies

Capital projects may address several objectives. Continuing enrollment growth has largely driven the University's requirement for new teaching laboratories, classrooms, student housing, and services. In 2019–20 alone, UC approved $285 million for projects that address enrollment needs. The campuses must expand teaching laboratories and classrooms to meet the increases in enrollment.

Program improvements and modern program initiatives require state-of-the-art space, often necessitating the repurposing of existing facilities or new construction. In 2019–20, UC devoted approximately $436 million for program improvements to address academic, research, and clinical priorities.

Campus facilities age and must be renewed and modernized to ensure safety, extend the buildings’ useful life, and improve energy efficiency. Building systems, elevators, and roofs need periodic replacement and renewal during the lifespan of a building. In 2019–20, UC approved $1.6 billion for these types of projects.

In addition to general renewal, the University continues to review the seismic safety of its facilities. UC devoted $319 million to seismic and life-safety improvements to buildings in 2019–20.

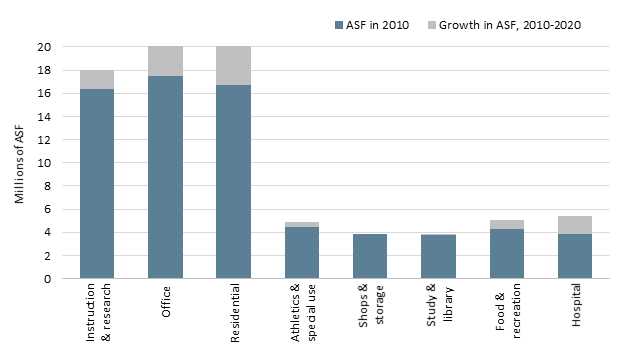

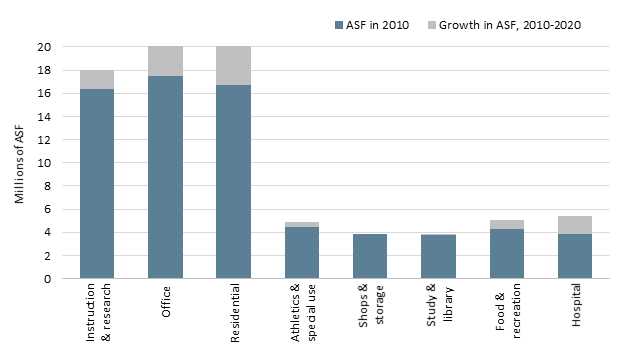

In the past decade, UC space has increased by approximately 16 percent, with most of the growth targeted for instruction and research, and residential uses.

12.2.4 Assignable square footage (ASF), Universitywide, 2010-2020

Source: UC Capital Asset Strategies

Assignable square footage (ASF) is the space available for programs or assigned to specific uses. It does not include corridors, bathrooms or building infrastructure.

Indicator 12.2.4 illustrates the growth in space over the last decade, according to categories for assignable space. Since 2010, space has increased by 11.5 million ASF for a total of 82 million ASF.

In the past decade, instructional and research space increased by about 1.6 million ASF, office space by 3.7 million ASF, and residential space by 3.4 million ASF. The space increase for these areas (17 percent) is has not kept pace to the to the increase in fall enrollment (25 percent) for the same period. Residential space has grown as campuses strive for more on-campus student housing to improve student life in living/learning communities and to reduce environmental impacts from commuting. Increases in the student population have also required additions to athletic, recreational, and food service space.

Hospital space grew significantly in the past decade. All five medical centers experienced growth but most of the growth in hospital space can be attributed to UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay and Ron Conway Family Gateway Medical Building (2015), and the Jacobs Medical Center at UC San Diego Health (2016).

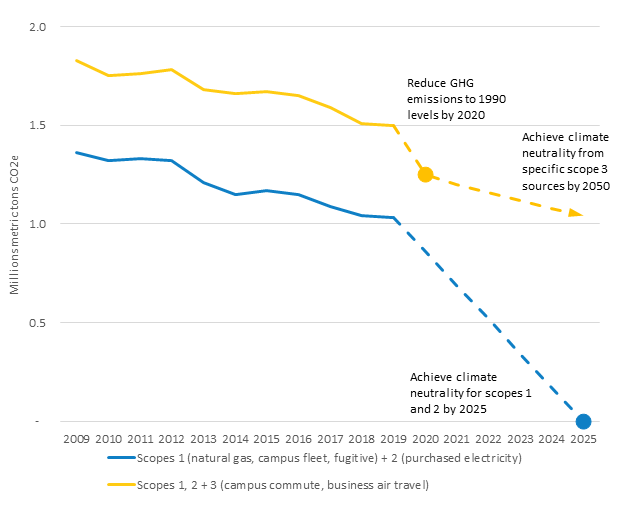

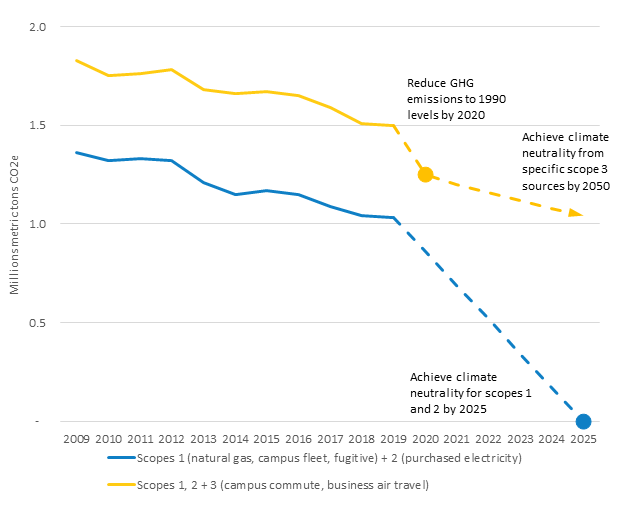

UC has made consistent progress toward its greenhouse gas emission goals.

12.3.1 Greenhouse gas emissions compared to climate goals, Universitywide, 2009–2025

Source: UCOP Energy and Sustainability Office

The University’s scope 1 and scope 2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions decreased by 15 percent since the Carbon Neutrality Initiative was announced in 2013, committing the University to carbon neutrality by 2025. This includes a one percent increase in scope 1 emissions and a 20 percent reduction in scope 2 emissions in 2019 compared to 2018. Scope 2 emissions in 2020 are expected to decrease even further as the UC Clean Power Program is now procuring 100 percent carbon neutral electricity.

The University also generates more on-site renewable energy than any other university in the country, approaching 50 megawatts. UC’s inventory of renewable energy supplies includes generation from over 100 on-site and off-site sources.

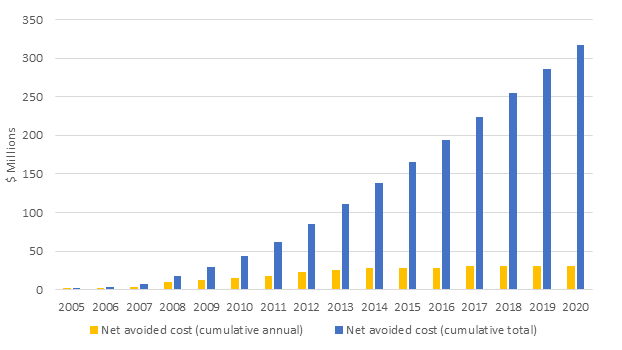

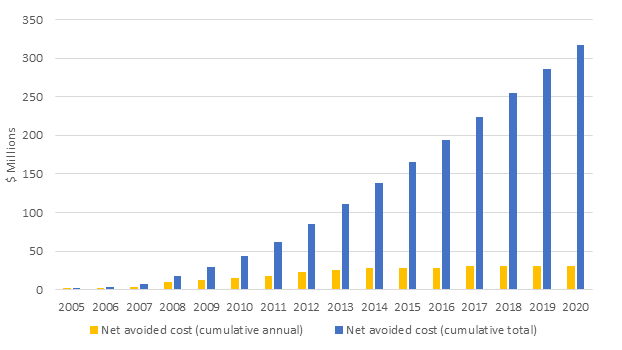

Energy efficiency upgrades resulted in cumulative net avoided costs for the University of $316 million by the end of 2020.

12.3.2 Cost avoidance from energy efficiency projects, Universitywide, 2005–2020

Source: UCOP Energy and Sustainability Office

In 2004, the University formed a statewide energy efficiency partnership program with California State University and the state’s four investor-owned utilities to improve the energy performance of higher education facilities. The partnership has provided funding for equipment retrofits and monitoring-based commissioning.

Since its inception, over 1,000 energy efficiency and new construction projects have registered with the Energy Efficiency Partnership Program, which has allowed UC campuses to avoid over $316 million in utility costs while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Sixty-one UC projects participated in the program in 2020.

While campuses have used a portfolio approach to balance projects with shorter and longer paybacks, the future focus on the remaining deeper energy efficiency retrofits to achieve climate goals will result in lower levels of net avoided costs due to larger up-front investments.

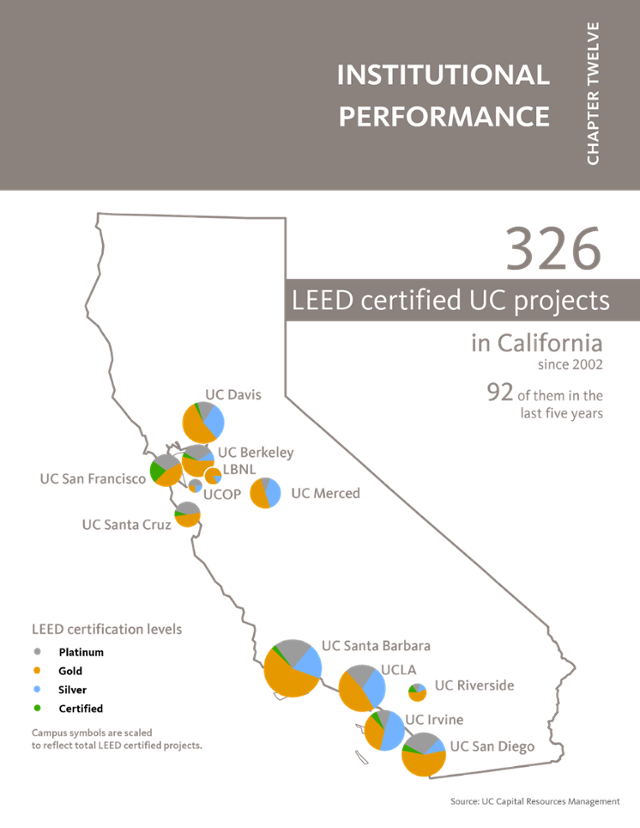

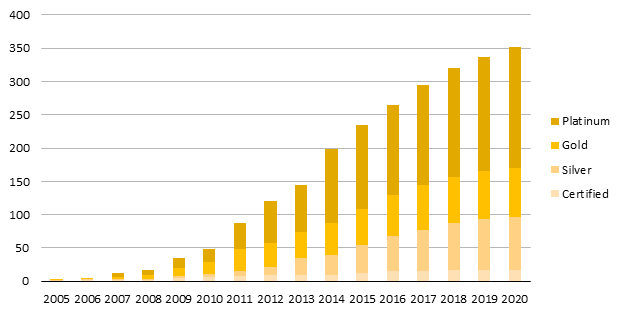

By the end of 2020, UC had achieved 352 LEED® certifications, more than any other university in the country.

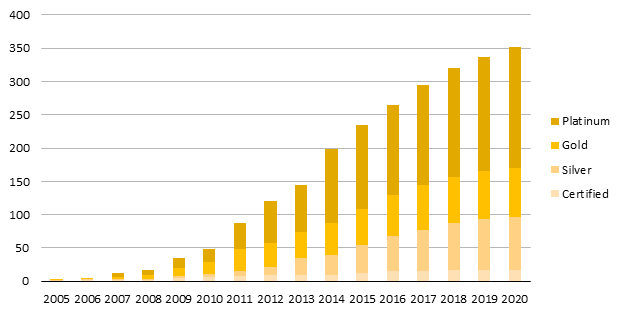

12.3.3 LEED® certifications, Universitywide, 2005-2020 (cumulative)

Source: UCOP Capital Resources Management

The University’s sustainable practices policy requires that all new buildings and renovations are designed and constructed to a minimum LEED® (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) for New Construction Silver rating. The policy also states that each campus shall seek to certify as many buildings as possible through the LEED – Existing Buildings, Operations and Maintenance (EBOM) rating system to “green” the day-to-day, ongoing environmental performance of its existing facilities.

UC has 352 LEED certifications systemwide, with 45 projects certifying under the LEED – EBOM system. In 2020, UC added fifteen new LEED certifications, including one new LEED Silver, ten LEED Gold and four LEED Platinum certifications. UC’s total of 352 LEED certifications is the most of any university.

UC LEED® certifications are listed at: ucop.edu/sustainability/policy-areas/green-building/index.html