Overview

The University of California's distinguished faculty and other academic appointees serve as a rich source of innovation, discovery, and mentorship. They provide top-quality education to students, develop groundbreaking research, and serve California’s diverse communities. Despite the operational and financial challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, UC faculty and other academic appointees quickly rose to the challenge of engaging in the University’s mission of teaching, research, and service in a remote environment. Recognizing the challenges faced by faculty and other academic appointees, the University of California adopted numerous programs and exceptions to policy, providing flexibility to faculty and other academic appointees to conduct their work.

Describing the academic workforce

Academic FTE and Headcount, October 2020

|

FTE |

Headcount |

| Faculty - Ladder-rank and Equivalent |

10,810.5 |

11,677 |

| Faculty - Clinical/In-Residence/Adjunct |

7,945.4 |

8,745 |

| Faculty - Lecturers |

2,402.9 |

4,006 |

| Other Academic Employees |

6,446.8 |

8,637 |

| Postdoctoral Scholars |

5,253.8 |

6,157 |

| Student Teaching/Research Assistants |

11,419.9 |

27,613 |

| Medical Interns/Residents |

6,001.6 |

6,177 |

| Grand Total |

50,280.9 |

73,012 |

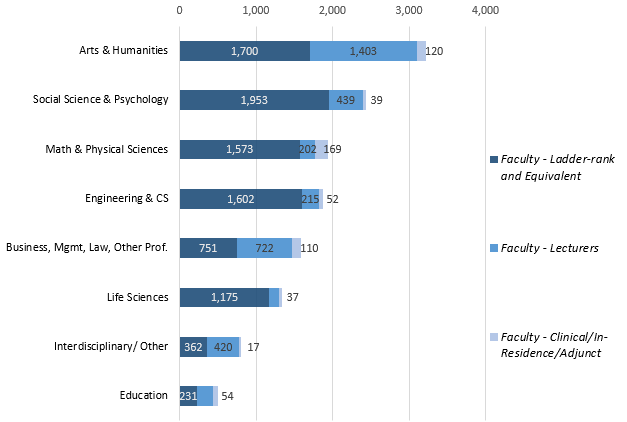

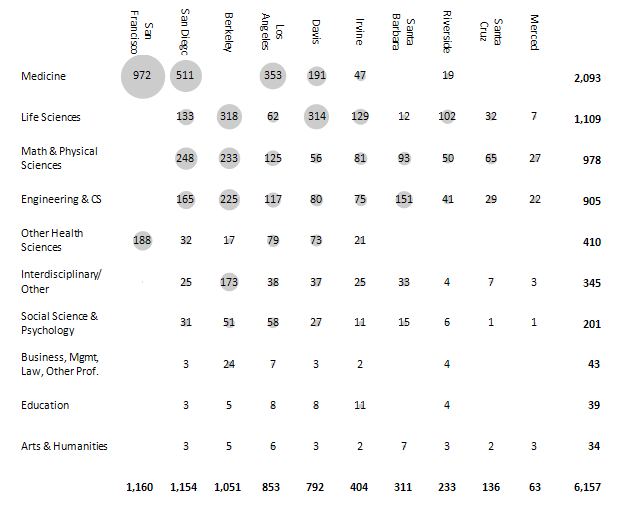

Faculty are the most prominent face of UC’s academic workforce, but there are many other academic roles, totaling over 50,000 full-time equivalents (FTE) across over more than 73,000 individuals. Over 59 percent of faculty are in general campus schools, while the other 41 percent are in the health sciences.

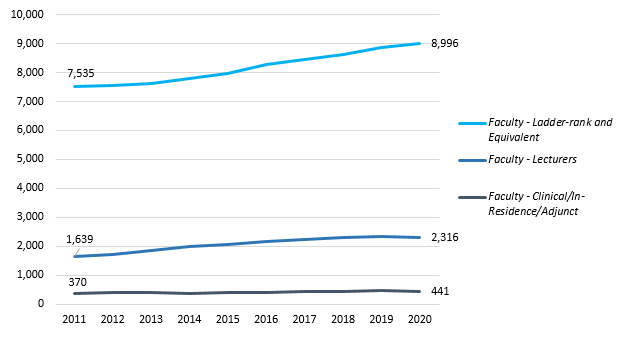

Ladder-rank and equivalent faculty are the core of the faculty in advancing the UC’s tripartite mission of teaching, research, and public service. These faculty can advance to tenure or equivalent status.1 In the past decade, ladder-rank and equivalent faculty FTE have increased by over 18 percent.

The In-Residence, Professor of Clinical (e.g., Medicine), Health Sciences Clinical Professor, and Adjunct Professor series faculty are found at all campus locations. However, their numbers are concentrated in the health sciences schools; their duties vary in their focus on research, clinical care, and teaching. Lecturers focus on instruction and are hired into part-time and full-time positions. Lecturers can achieve continuing status.

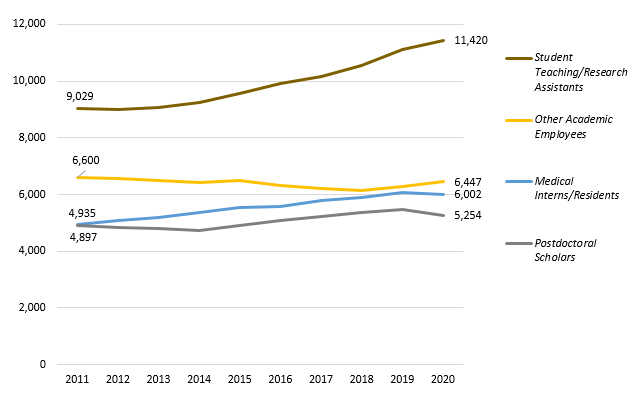

Postdoctoral scholars conduct research under the general oversight of a faculty mentor. They are typically paid through research contracts and grants, so their numbers concentrate in the medical and STEM fields and vary with available grant funding.

Other academic appointees include academic researchers, cooperative extension advisors, and specialists in cooperative extension; librarians; faculty administrators such as Deans; university extension instructors; graduate students appointed as Teaching Assistants and Research Assistants; and residents and interns in medicine and other academic health sciences programs.

1 Security of Employment or the tenure-equivalent of associate and full agronomists and astronomers. Diversity

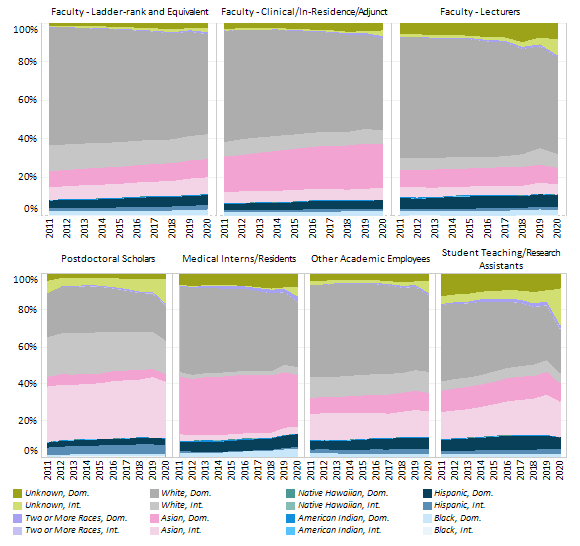

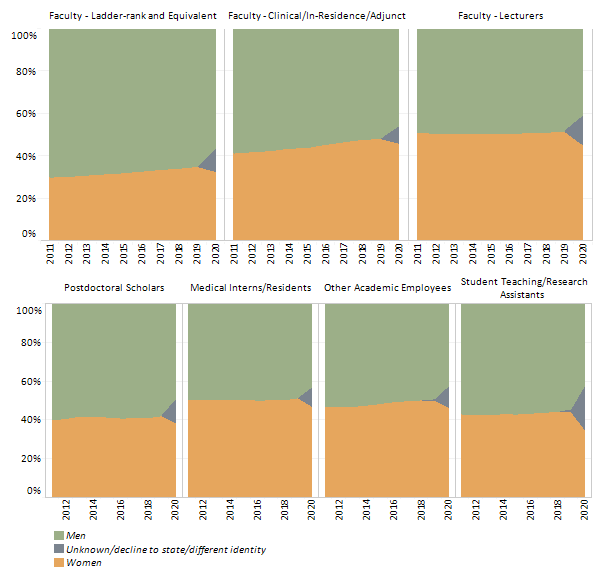

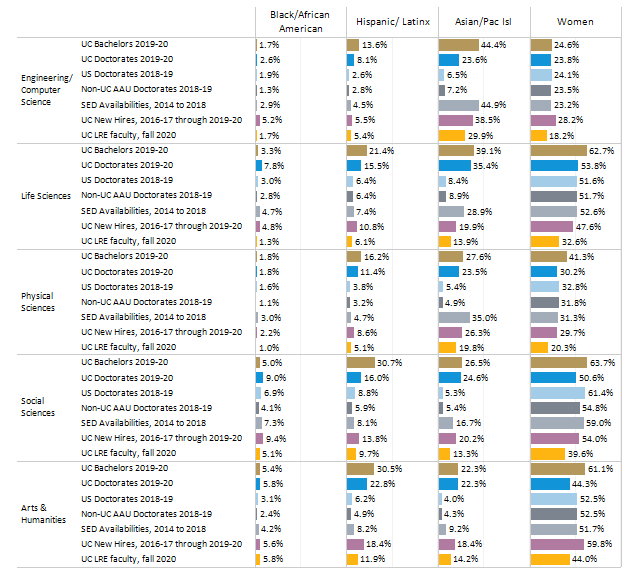

The University of California is committed to diversity and excellence in its faculty and academic workforce. The proportion of women, African American, and Hispanic/Latinx faculty has grown at a modest pace. Newer faculty cohorts are more diverse than past cohorts.

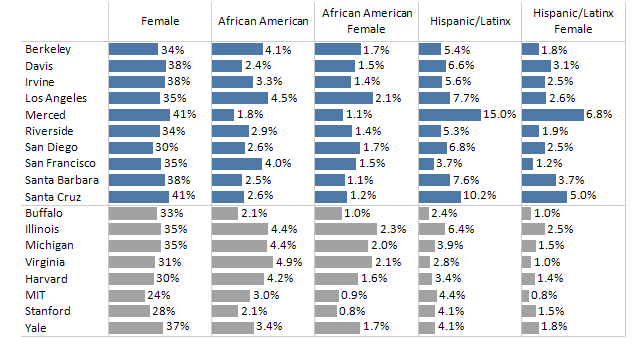

Among tenured and tenure-track faculty, UC compares favorably in terms of the proportions of women, African American, and Hispanic/Latinx faculty relative to the comparison eight peer research institutions.2 Still, UC continues to work to identify opportunities to diversify the faculty and improve recruitment processes and campus climate by tracking recruitment data, by sharing best practices in mentoring and professional development, and by enhancing work-life balance programs.

Varieties of programs have been put in place to strengthen faculty diversity:

Advancing Faculty Diversity — The State of California awarded UC a total of $8.5 million in one-time funds for four fiscal years, from 2016–17 to 2019–20, to develop an innovative and focused program to increase faculty diversity at UC. The Advancing Faculty Diversity (AFD) program awards these funds on a competitive basis to campus units implementing new, measurable interventions in the faculty recruitment process. In addition, since 2018–19, twenty awards have been funded by the Office of the President to improve academic climate and increase faculty retention. Some of the successful interventions that correlate with hiring diverse faculty include the use of contributions to diversity statements early in the evaluation process; targeting potential faculty earlier in their careers through support for postdoctoral work; outreach by faculty to actively recruit candidates; revised evaluation practices, including the use of rubrics to guide decision-making; strong leadership and sustained and strategic involvement from unit leaders; introducing new voices, including students, in the recruitment and evaluation process; building of new faculty, equity, and inclusion data dashboards; research on and support for pathways to faculty leadership positions; and examinations of whether service loads differ by gender or race/ethnicity. Since 2019–20, UCOP committed an additional $3 million per year in ongoing funds to support additional projects in faculty recruitment; improve climate and retention to pilot innovative recruitment practices; create academic climates to support UC’s diverse student body and meaningfully engage faculty throughout their UC careers. Since its inception, a total of forty recruitment and improved climate and retention projects have been funded through the AFD program’s competitive process, with all ten campuses receiving at least one award.

President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (PPFP) — Established in 1984, the PPFP recruits top scholars who are committed to underserved and minority communities to pursue faculty careers at UC. Between 2016–17 and 2020–21, UC hired 112 fellows as ladder-rank faculty at all ten UC campuses. In addition, more than 20 fellows have been successfully recruited for UC faculty positions that will begin in 2021–22, with 19 others still under consideration. Through Presidential support, UC has increased the number of incentives available to departments that hire fellows and expanded eligibility for hiring incentives to include the health sciences and professional schools. The program is nationally recognized and it leads a partnership of top universities that participate in recruiting top postdoc talent.

2 The comparison eight institutions are University of Illinois, University of Michigan, University at Buffalo, University of Virginia, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, and Yale University.

Hiring and retention

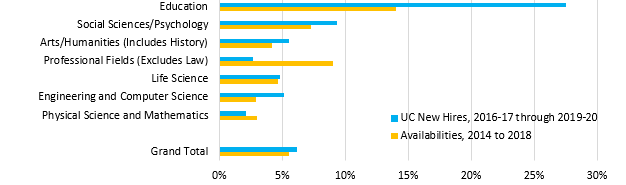

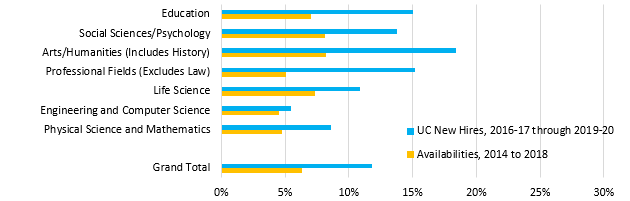

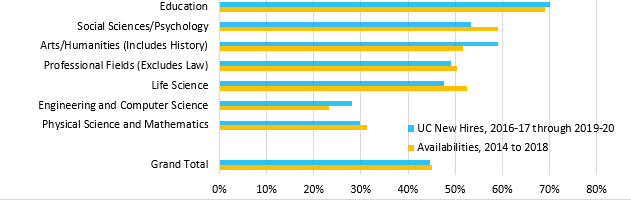

Overall hiring of UC faculty generally outpaces availabilities of U.S. doctoral degree recipients by race, ethnicity, and gender, with some notable differences by field. STEM fields have a more limited ability to diversify based on Ph.D. availabilities. UC is also looking at the diversity of its own student populations, including bachelor and graduate degree recipients, to increase the diversity of UC’s future professoriate.

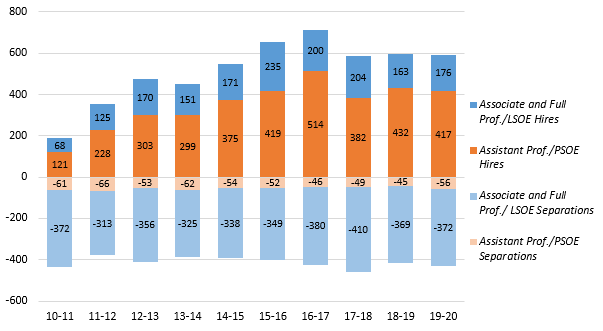

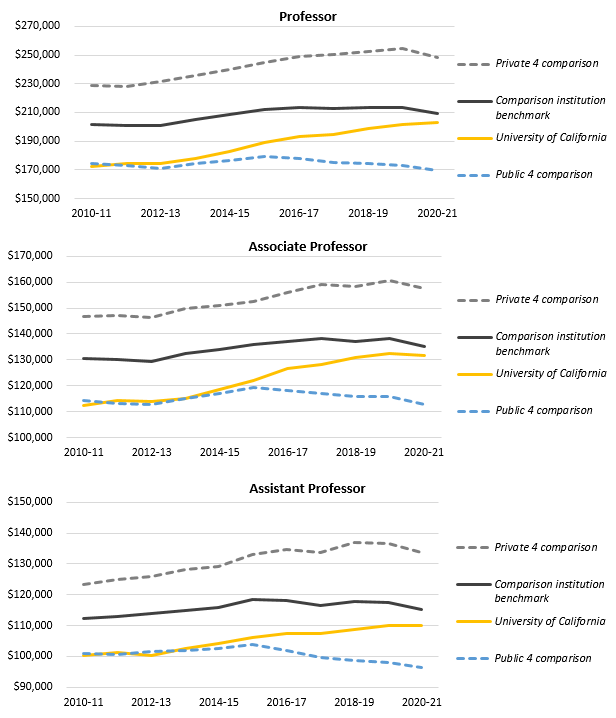

In recent years, faculty hires have stabilized after several years of increases as UC recovered from severe budget cuts a decade ago and as enrollment growth demanded greater teaching capacity. Faculty separations have grown modestly, primarily due to increasing retirements. UC campuses have drastically scaled back their faculty recruiting due to the economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it remains to be seen how soon faculty recruiting can return to a growth trend. Average faculty salaries at UC have improved somewhat in recent years; however, they still trail those at many comparison institutions, particularly a benchmark of the average of salaries at the “Comparison 8,” a group of four public and four private institutions.

UC 2030 goals

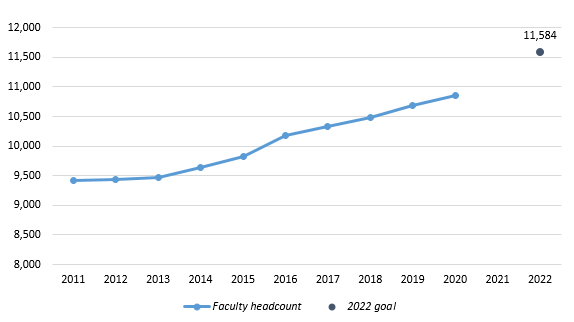

As part of the multi-year framework adopted by the UC Regents in early 2019, known as UC 2030 — Advancing the California Dream, UC is hoping to receive additional State support to hire 1,100 ladder-rank faculty between 2018–19 and 2022–23 (5.3.5). Since setting the hiring goal, the University’s faculty has grown by nearly 400, or about 3.6 percent. To reach the hiring goal by 2022–23, UC needs to add 700 faculty, or about 6.6 percent, over the next two years. The University is at risk of not achieving this goal as the requisite hiring rate is nearly double that of recent trends. Nonetheless, with growth, UC is hoping to continue to increase the diversity of its ladder-rank faculty, which also involves retaining faculty who contribute to that diversity.

Between 2014 and 2020, the share of Universitywide faculty who are African American increased from 2.7 percent to 3.5 percent, and the share who are Hispanic/Latinx increased from 6.4 percent to 7.9 percent. The number of African American faculty members went from 256 to 381, a 49 percent increase, and the number of Hispanic/Latinx faculty members increased from 614 to 855, a 39 percent increase.

For more information