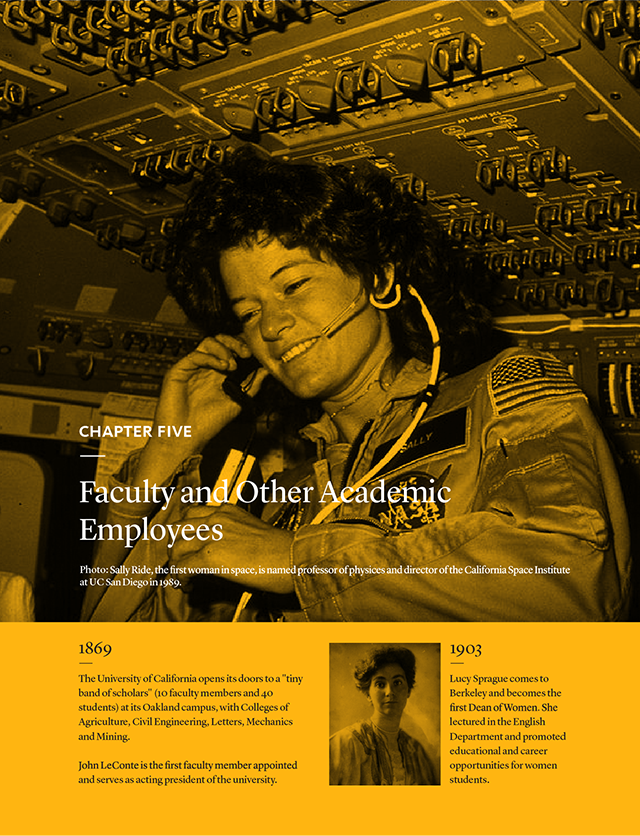

History

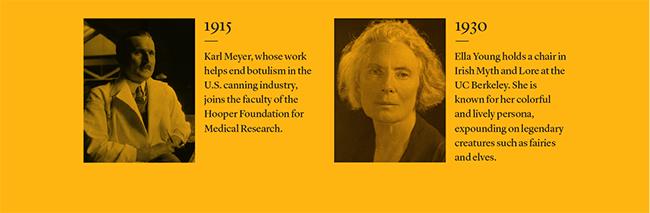

As soon as it was founded, the University quickly attracted eminent faculty. Daniel Coit Gilman of Yale became the second president of the University in 1872; Eugene W. Hilgard, nationally renowned geologist and soil chemist, joined the faculty in 1875 and laid the foundations for the College of Agriculture, helping turn the Central Valley into one of the world’s most productive farming regions; and Willis Jepson, professor of botany, helped establish the herbarium at Berkeley, the California Botanical Society, and the Sierra Club.

In 1920, the UC regents formally recognized the Academic Senate and its role in the governance of the University. Though the Academic Senate does not include all faculty members, it is an important body whose responsibilities include authorizing, approving and supervising all courses and determining the conditions for admissions, certificates and degrees. The Senate may advise the president and chancellors on budget matters and on the administration of the libraries, and participates in searches for deans, chancellors and the president.

Overview

The University of California’s distinguished faculty and academic employees serve as a rich source of innovation, discovery and mentorship. They provide top-quality education to students, develop groundbreaking research and serve California communities. No other public institution can claim so many distinguished academics: 62 Nobel Prizes, 63 National Medals of Science, 88 MacArthur Genius Awards, 9 National Humanities Medals, 41 Pulitzer Prizes, to name a few. President Napolitano has said, “We teach for California … [and] we research for the world.”

Describing the academic workforce

Academic FTE and Headcount, October 2017

|

FTE |

Headcount |

| Faculty - Ladder-rank and Equivalent |

10,158.6 |

11,065 |

| Faculty - Clinical/In-Residence/Adjunct |

6,978.5 |

7,885 |

| Faculty - Lecturers |

2,300.8 |

3,765 |

| Other Academic Employees |

6,205.6 |

8,445 |

| Postdoctoral Scholars |

5,230.4 |

6,433 |

| Medical Interns/Residents |

5,771.6 |

5,934 |

| Student Teaching/Research Assistants |

10,163.3 |

24,931 |

| Grand Total |

46,808.9 |

68,458 |

Faculty are the most prominent face of UC’s academic workforce, but there are several types of faculty and other academic roles as well, totaling nearly 47,000 full-time equivalents (FTE) across over 68,000 individuals. About 60 percent of academic roles fall under general campus while the other 40 percent support the health sciences and medical centers. Since 2000, all faculty groups have grown, but lecturers have grown faster than other faculty.

Non-faculty academic positions have grown as well, notably student assistants and medical interns. Postdoctoral scholars are sponsored by faculty and typically paid through research contracts and grants, so their numbers concentrate in the Medical and STEM fields and vary with available grant funding.

Diversity

The University of California is committed to diversifying its faculty and academic workforce. The proportion of women and underrepresented (African American, American Indian, and Hispanic/Latino(a)) groups in the faculty continues to grow at a modest pace. Younger faculty cohorts are noticeably more diverse than older cohorts.

Compared to ladder-rank faculty, many other academic positions are more ethnically diverse and gender balanced because they experience more rapid turnover. Still, when comparing UC’s faculty diversity to peer research institutions, UC places 3rd in terms of female faculty and 2nd in terms of underrepresented faculty. More must be done, and UCOP is working with campuses by tracking recruitment data to identify opportunities to diversify the faculty; by sharing best practices in mentoring and professional development; and by enhancing work-life balance programs.

A variety of programs have been put in place to strengthen faculty diversity:

Advancing Faculty Diversity — For two years, the state of California has provided $2 Million to support efforts to increase faculty diversity at UC. Through a competitive process, UC has selected seven pilot units, each of which has developed a distinctive recruitment program for the 2016-17 or 2017-18 fiscal year. During both years, campus units used the funds to support interventions that would recruit diverse candidates to a university committed to its diverse students and communities. Some of the successful practices included enhanced outreach; use of a postdoctoral year to recruit top candidates; tapping into the proven talent of the diverse fellows in the President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program and the Chancellors’ Postdoctoral Fellowship Program; intervening in traditional evaluation practices; inclusion of students in the hiring process; making use of campus equity advisors; creating peer-mentoring cohorts of new faculty; and hiring at the senior level through endowed chairs.

President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (PPFP) – Established in 1984, the program recruits top scholars who are committed to underserved and minority communities to pursue faculty careers at UC. An increasing number of Fellows have been hired as UC faculty in recent years; in 2017-18, numbers reached an all-time high. This year, UC increased the incentives available to departments who hire fellows and the program was expanded to include all disciplines. The program is nationally recognized and leads a partnership of top universities that participate in recruitment.

Grant-funded research — In 2015, UC was awarded a National Science Foundation grant to study the faculty hiring process over a three-year period. The study is identifying steps in UC’s hiring process susceptible to bias, characteristics that amplify or mitigate disparities, as well as policies to promote faculty equity, inclusion and diversity. UC was also awarded a five-year grant to establish the Center for Research, Excellence and Diversity in Team Science (CREDITS), a research and training program to enhance the capacity, effectiveness and excellence of team science efforts at UC and CSU. CREDITS researches gender and racial/ethnic diversity in team science, particularly barriers to diverse participation and how diversity shapes the formation of science teams and the implications for promotion and tenure.

UC Davis Center for Multicultural Perspectives on Science (CAMPOS) — Established in 2013, the center incentivizes the hiring of STEM faculty committed to doing outreach, mentoring or research in underserved communities. Its scholars are ladder-rank faculty selected based on transformative thinking, perspectives, interdisciplinary approaches and leadership potential. The Center started with a focus on Latina STEM scholars and has expanded to all underrepresented groups in STEM.

Hiring and retention

UC’s faculty hires show that hiring generally matches to availabilities of U.S. doctoral degree recipients by ethnicity and gender, but varies by field. For a variety of reasons, STEM fields have limited ability to catch up on diversity based on these availabilities.

Over the last few years, faculty hires have increased as UC has recovered from severe budget cuts and as enrollment growth has demanded greater teaching capacity. Departures have remained steady. Faculty salaries at UC have improved somewhat in recent years; however, they still trail those at many comparison institutions, particularly a benchmark of the average of salaries at the “Comparison 8,” a group of four public and four private institutions.

Even in retirement, UC faculty remain active and are recognized for their contributions. A Council of University of California Emeriti Associations (CUCEA) survey showed that between 2012 to 2015, UC emeriti taught more than 2,000 classes, wrote more than 500 books and over 3,000 articles, and were involved in hundreds of campus and community service efforts. In early retirement, many faculty still work with graduate students on research, run labs or have grants with time remaining.

For more information

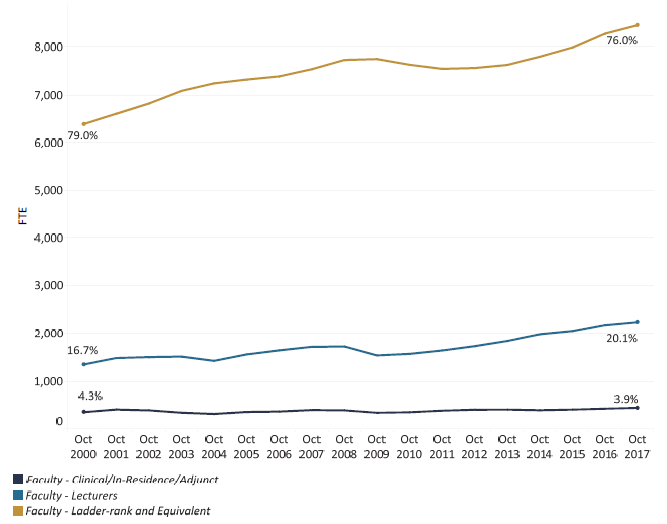

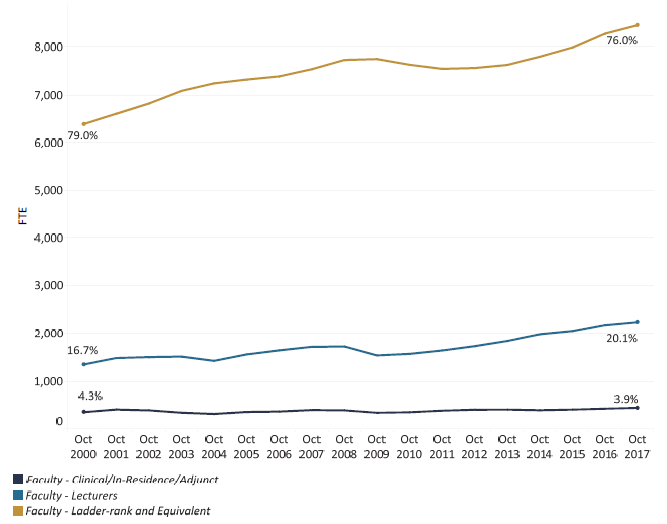

UC faculty have increased to accommodate a growing student body, relying more on term faculty today than in years past.

5.1.1 General Campus faculty FTE total by type, Universitywide, October 2000 to 2017>

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System

Since 2000, faculty has increased by over 3,000 FTE, or over 37 percent. While all faculty types have grown, the most pronounced increase has been among lecturers, who grew over 65 percent during this period. Lecturers made up more than 20 percent of general campus faculty FTE in October 2017, a slight increase from 17 percent in 2000.

Ladder-rank faculty have grown at a more modest 32 percent, but they still make up 76 percent of faculty FTE. FTE in the Clinical/In-Residence/Adjunct faculty series are typically associated with health sciences, so they only represent a small portion (4 percent) of overall general campus faculty.

Reliance on lecturers has become more common in higher education in recent years. At UC, lecturers do not have research responsibilities and therefore focus on teaching. These faculty help meet the instructional needs of UC’s growing enrollment.

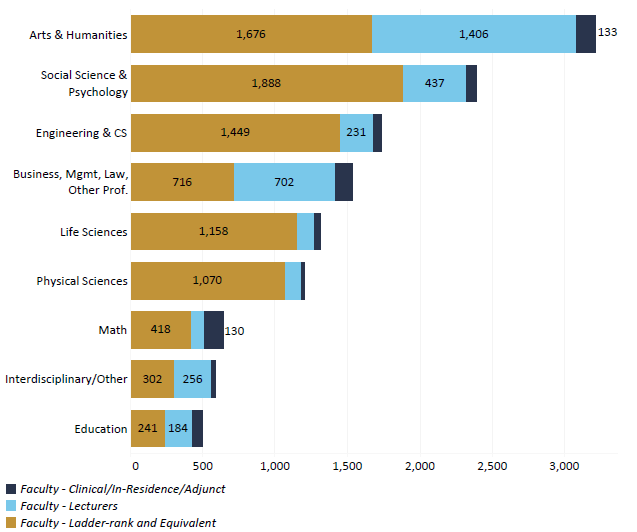

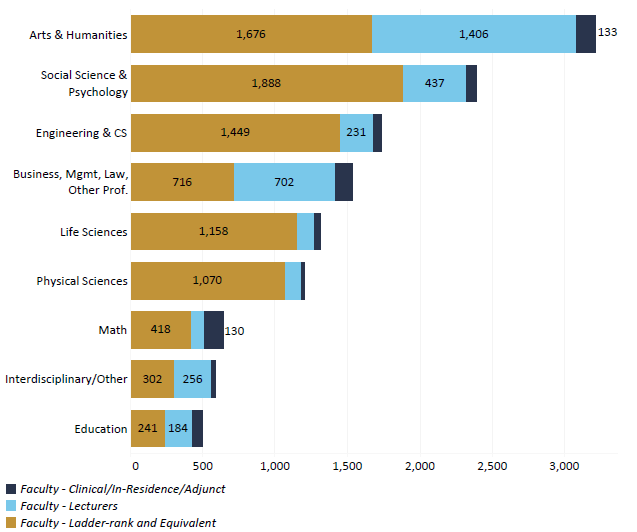

General campus faculty are most concentrated in arts and humanities and the social sciences, and a variety of STEM fields.

5.1.2 General campus faculty headcount by discipline, Universitywide, October 2017

Source: Corporate Personnel System

Faculty fall into hundreds of departments across the ten campuses. While most health sciences faculty are classified under medicine and other health sciences, general campus faculty are spread across a spectrum of disciplines. The disciplines with the most undergraduate majors tend to represent the largest groups. Arts and Humanities may be especially high due the smaller class sizes required to teach many general education courses.

Different disciplines rely on varying types of faculty to fulfill their teaching and research missions. Lecturers are also concentrated in certain disciplines, such as Arts and Humanities, often to support general education requirements in those areas.

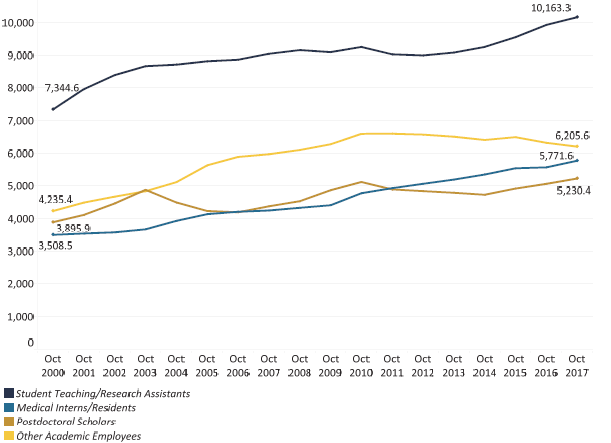

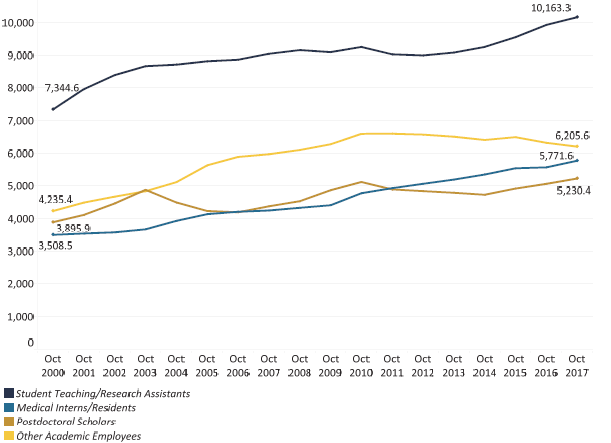

The non-faculty academic workforce has increased steadily, particularly among student assistants and medical interns. Other Academic and postdoctoral growth aligns closely with faculty growth and the availability of research funding.

5.1.3 Non-faculty academic workforce FTE, Universitywide, October 2000 to 2017

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System

The non-faculty academic workforce has expanded alongside student and faculty growth since 2000. There are nearly 8,500 additional FTE over this period, with overall growth of 45 percent.

Student teaching and research assistants as well as medical interns/residents have grown considerably, constituting over 5,000 of the FTE growth. Most student assistants are graduate students and therefore part-time, which means that the FTE growth represents a larger headcount growth of close to 7,000 individuals. Enrollment increases and expansion of medical programs over this time explain this growth.

Postdoctoral scholars and other academics, two groups heavily concentrated on the research mission, have also grown in line with faculty. Contracts and grants from external sponsors support the vast majority of researchers in the academic workforce, with the federal government providing most research funding. A drop in federal research funds after 2010 flattened other academic growth and reduced postdoctoral FTE in the years following. Chapter 9, Research, provides additional details on the composition of the research workforce.

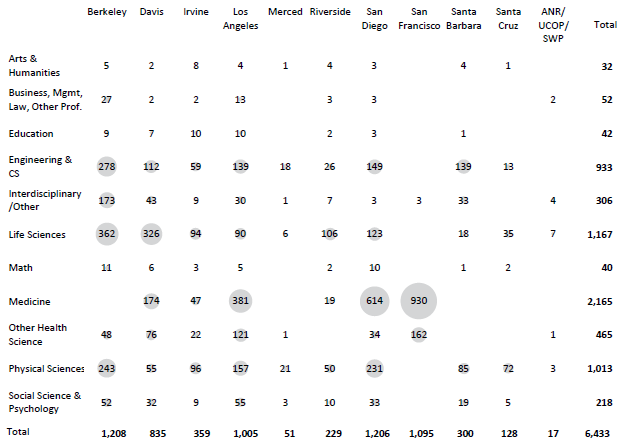

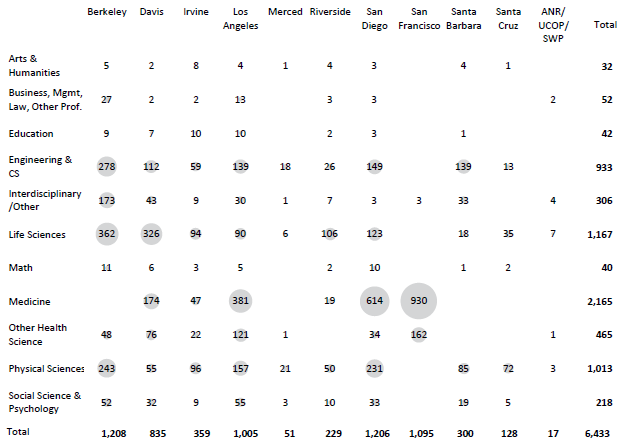

Postdoctoral scholars are concentrated in medicine, science and engineering.

5.1.4 Postdoctoral scholar headcount, By campus and discipline, October 2017

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System

Postdoctoral scholars have doctorate degrees and conduct research with faculty. Because most of their funding comes from contracts and grants, they are particularly prevalent in fields that receive large amounts of grant funding such as medicine, life sciences, physical sciences and engineering. Campuses with large research programs in these fields consequently have larger postdoctoral populations.

Beyond direct research, postdoctoral scholars mentor graduate and undergraduate students in the laboratory and may have formal supervisory functions in the laboratory.

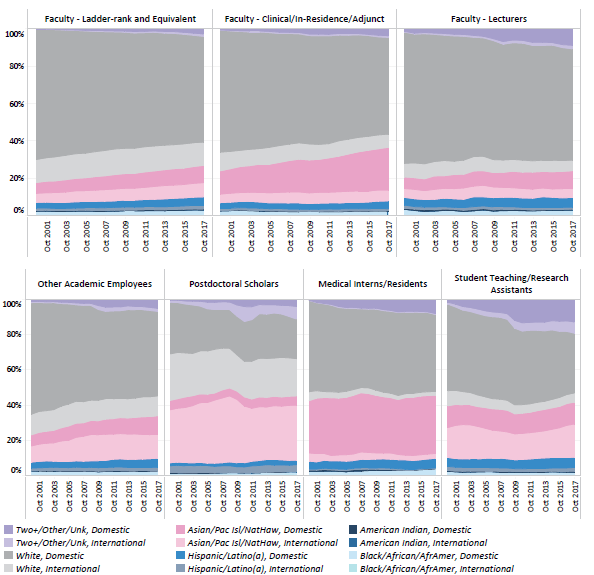

UC’s academic workforce is increasingly diverse, with notable differences in diversity among the types of employees.

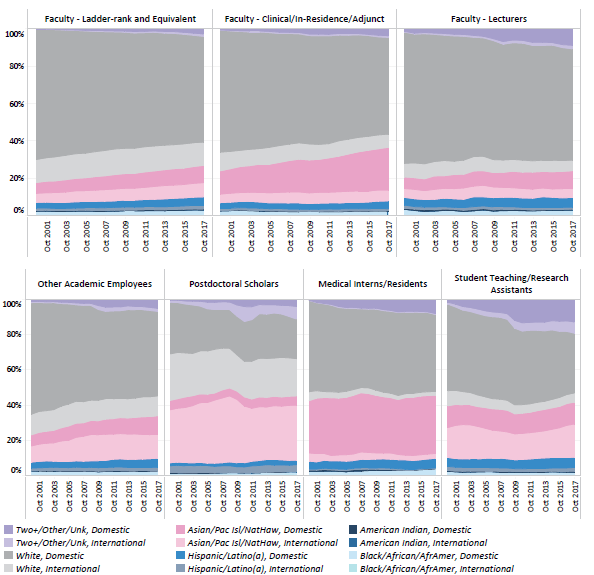

5.2.1 Academic workforce race/ethnicity by type, Universitywide, October 2000 to 2017

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System

All academic positions have increased in racial/ethnic diversity since the millennium. The share of academic employees who report two or more races/ethnicities has grown quickly since the introduction of this reporting category in 2010. Campus, discipline and age detail is available through the UC Information Center.

Positions with shorter durations tend to be more diverse, since turnover allows for increased diversity in hiring. Ladder-rank faculty diversity has been the slowest to change due to long tenures and limited availability of candidates in some disciplines.

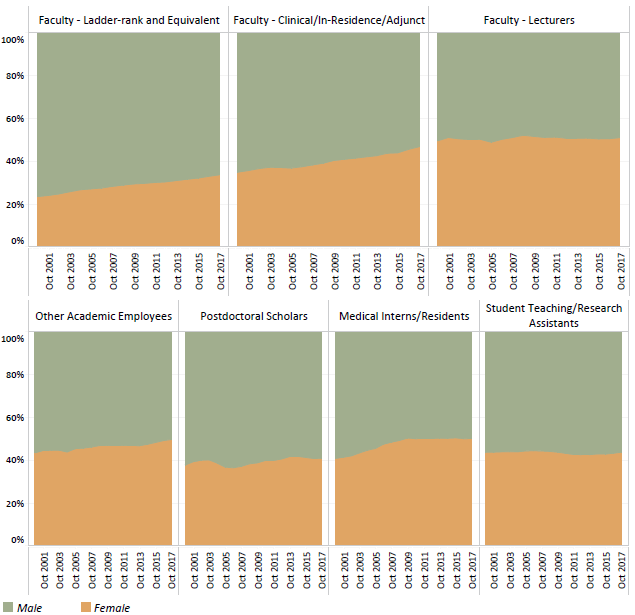

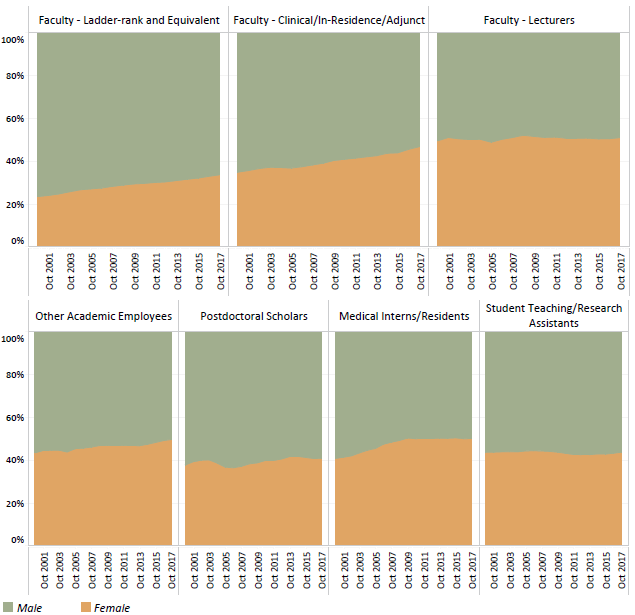

Gender diversity has increased or maintained parity among every academic group but still falls short of parity in several categories of academic appointees.

5.2.2 Academic workforce gender by type, Universitywide, October 2000 to 2017

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System

Today, women make up nearly half of lecturers, other academics and medical interns/residents. The ratio of women among Clinical/In-residence/adjunct faculty and ladder-rank faculty has risen. Gender diversity initiatives take longer to change populations such as ladder-rank professors where turnover is low and tenures are long. Postdoctoral scholars and student assistant ratios have remained relatively flat, likely related to the concentrations of those roles in fields that skew male.

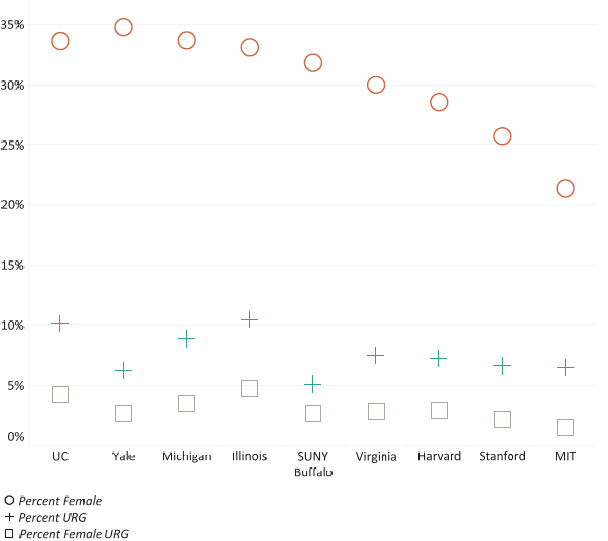

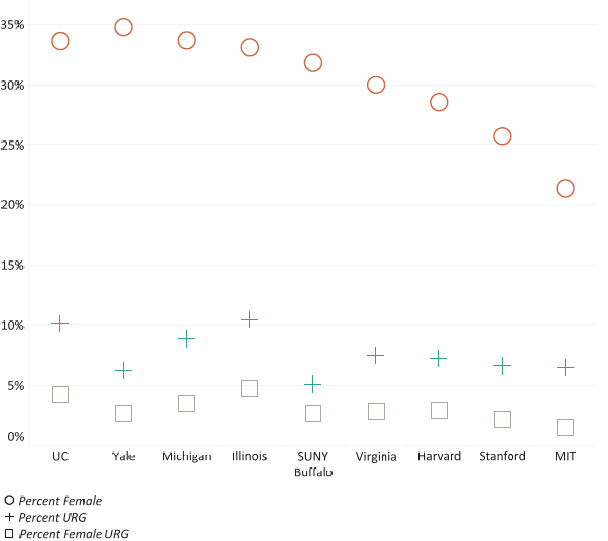

UC has greater faculty diversity in terms of women and under-represented minorities than many peers.

5.2.3 Percent of tenure and tenure-track faculty who are female and/or from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups, UC and comparison institutions, Fall 2016

Source: IPEDS. UC includes UC Hastings.

UC’s efforts to recruit women and underrepresented (American Indian, African American, and Hispanic/Latino(a)) groups (URGs) into faculty roles puts it near the top among peer research institutions in faculty diversity.

Relative to the “Comparison 8” universities (four public institutions: Illinois, Michigan, University at Buffalo, Virginia; four private institutions: Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Yale), UC has the third highest proportion of women at 33.6 percent. Regarding URG, UC has 10.1 percent overall URG and 4.3 percent female URG, placing it second amongst its peers.

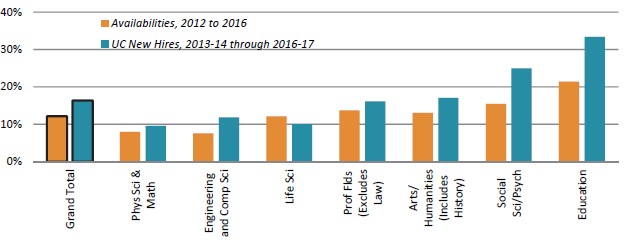

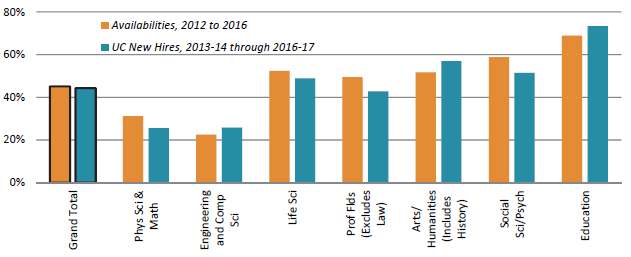

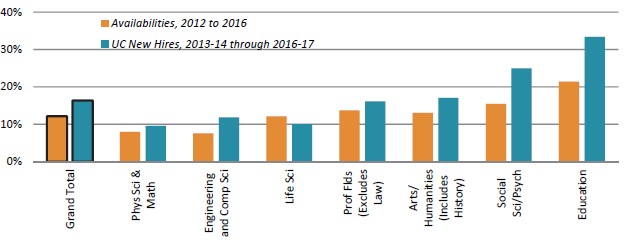

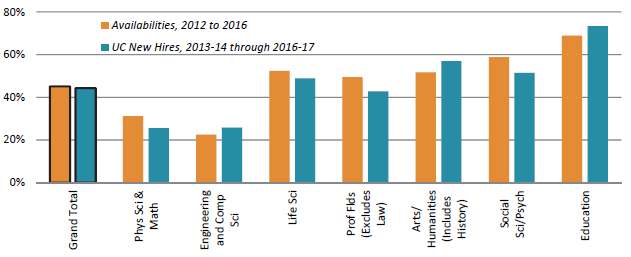

UC’s hiring of underrepresented and women faculty lags behind the national availability in several broad discipline groups.

5.3.1 Underrepresented* new assistant professors compared with national availability by discipline, Universitywide, 2013–14 to 2016–17

5.3.2 Female new assistant professors compared with national availability by discipline, Universitywide, 2013–14 to 2016–17

Source: UC Academic Personnel and Program Administration and Survey of Earned Doctorates

UC remains committed to diversifying its faculty and taking full advantage of the available pools of qualified candidates. Between 2012 and 2016, underrepresented groups accounted for 12.2 percent of nationwide new doctoral degree recipients and 16.4 percent of UC’s new assistant professor hires. Between 2012 and 2016, women constituted 45.1 percent of nationwide new doctoral degree recipients and 44.3 percent of UC’s new hires. Some disciplines exhibit greater success in outreach, recruitment and hiring efforts at UC than others, relative to the availability pools in their field.

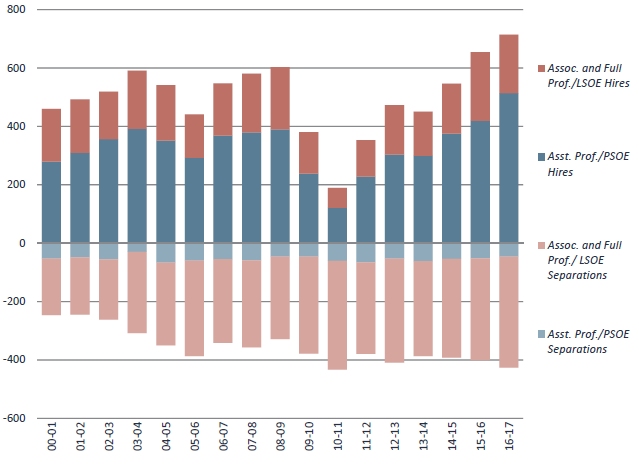

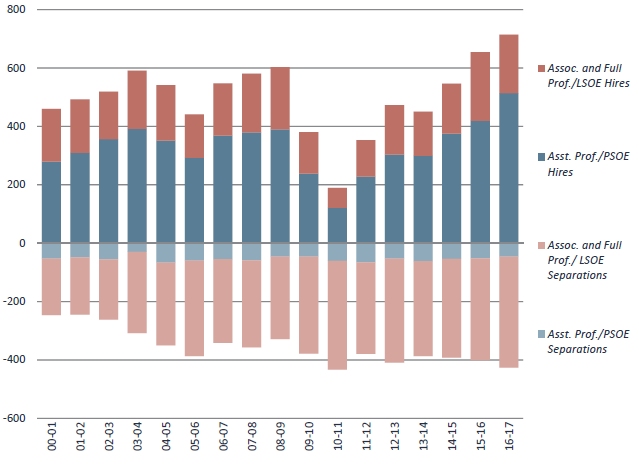

In the past few years, hiring of new faculty has started to rebound from a drop in fiscal years 2010 and 2011 due to state budget cuts.

5.3.3 New hires and separations of ladder-rank and equivalent faculty, Universitywide, 2000-01 to 2016-17

Source: UC Academic Personnel and Program Administration

As faculty numbers have grown, hiring has generally outpaced separations. Separations have stayed fairly constant despite shifts in demographics, the economy and state funding.

UC has partnered with Harvard's Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education (COACHE) on a research project to survey faculty who leave UC for employment at other universities. This Retention and Exit Study, now in its third year, is part of an effort to better understand and improve the experience of UC faculty members, as well as improve recruitment and retention.

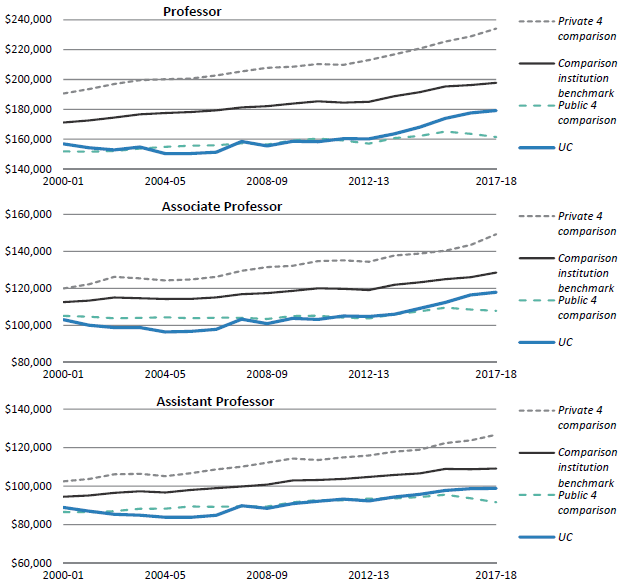

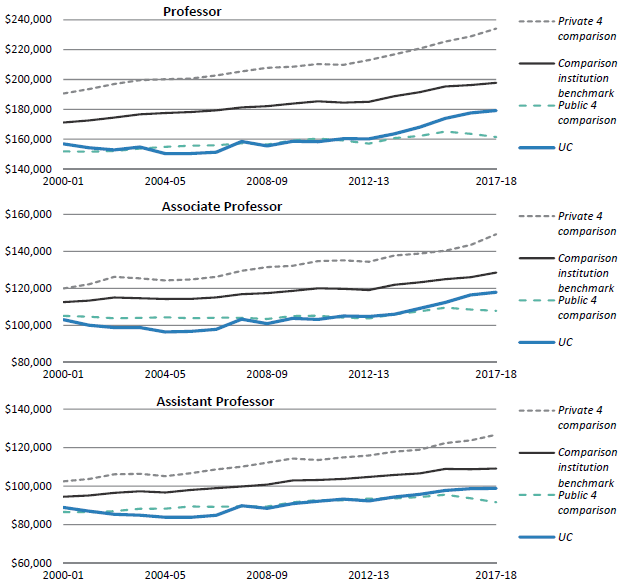

UC faculty salaries are currently below the benchmark that UC has historically employed to assess competitiveness. This affects the University’s efforts to recruit and retain high-quality faculty.

5.3.4 Average ladder-rank general campus faculty salaries, by rank, UC and comparison institutions, 2000–01 to 2017–18

Source: UC Corporate Personnel System, AAUP faculty salary survey

UC continues to lag the comparison benchmark it uses to assess the competitiveness of its faculty salaries. UC has sets the benchmark using the average salaries of the “Comparison 8” universities (four public - Illinois, Michigan, University at Buffalo, Virginia; four private - Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Yale).

UC’s faculty salaries fall significantly below those of the comparison private institutions, and are just recently pulling above the four public institutions. Notably, this comparison does not factor in the cost of living, which is especially high in most of California compared to the public peers assessed here.