Academic departments in ecology, evolution, and conservation biology are increasingly aware of the need to address longstanding barriers and challenges faced by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in these disciplines. A diverse group of faculty, staff, and students in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (EEB) at UC Santa Cruz has now compiled a set of tools and strategies which departments can use to address shortcomings in equity and inclusion.

Published August 9 in Nature Ecology & Evolution, the recommendations are based on a review of the literature in an effort to identify evidence-based interventions for fostering anti-racism in the classroom, within research labs, and department-wide. “There’s nothing novel in our recommendations. These are empirically-based approaches developed by people who study these issues, and we’ve put them all in one place and tailored them for the disciplines of ecology, evolution, and conservation biology,” said first author Melissa Cronin, a Ph.D. candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at UCSC. Cronin said she and senior author Erika Zavaleta, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, saw a growing need for an easily accessible set of resources to help departments wanting to address historic and current inequities in their fields.

Cronin and Zavaleta recruited a diverse group of students, faculty, and staff within their department to work on the paper, which has 26 coauthors. “It was a really positive and constructive experience for our department to work together on this paper,” Cronin said. “And we built on this incredibly rich tradition of scholarship at UC Santa Cruz in critical race studies, a field which historically has not always intersected with the STEM fields.”

Overview

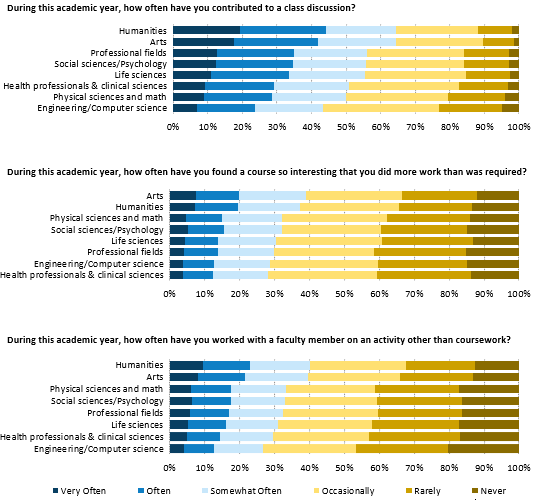

The University of California provides its students with a rich learning environment created by faculty engaged in both teaching and academic research. Student learning at UC involves classes, seminars, and lab sections enhanced by collaboration with faculty and researchers. Through these activities, faculty and students engage in a learning process that helps develop critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving skills, as well as discipline-specific knowledge.

Educating students and the public

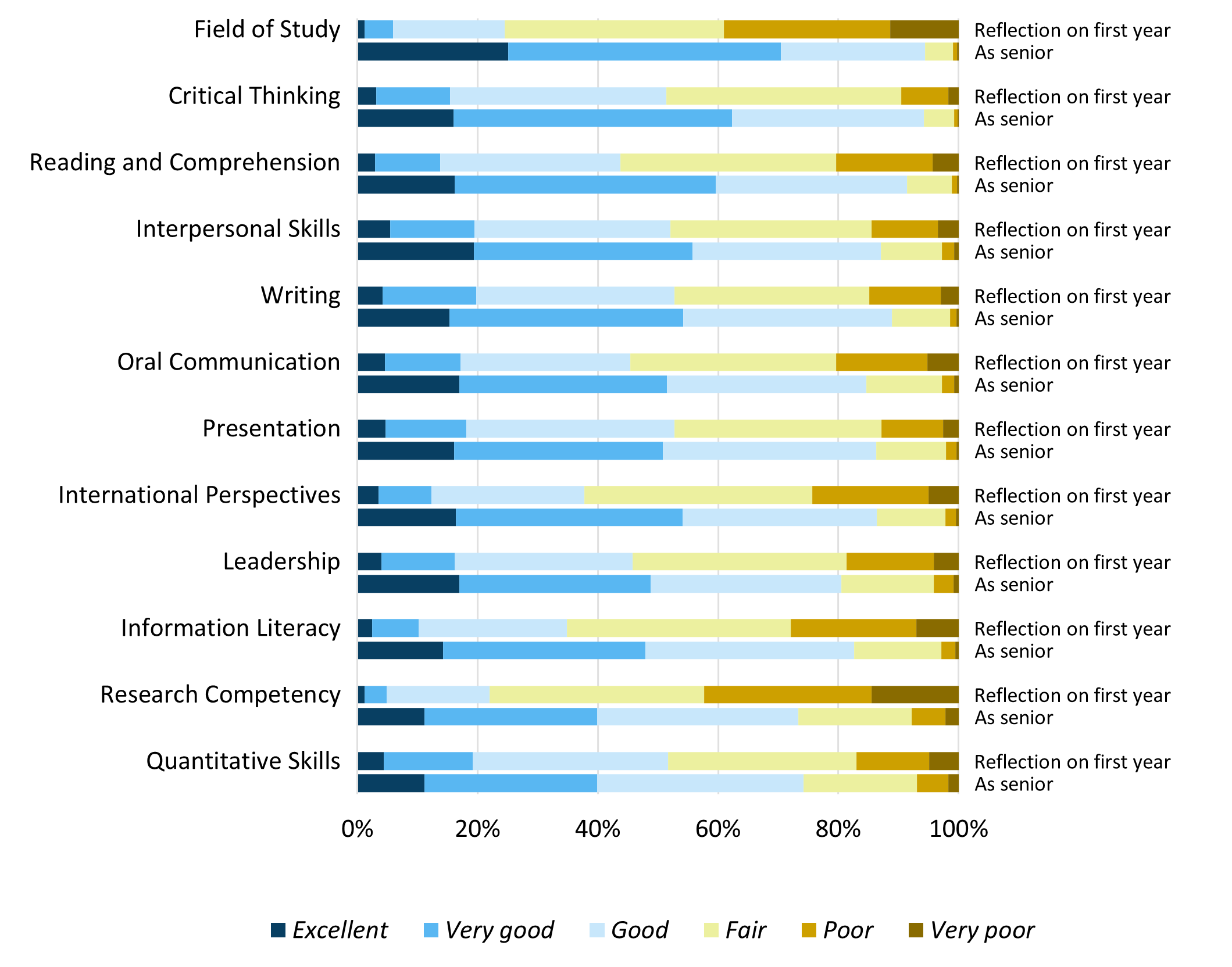

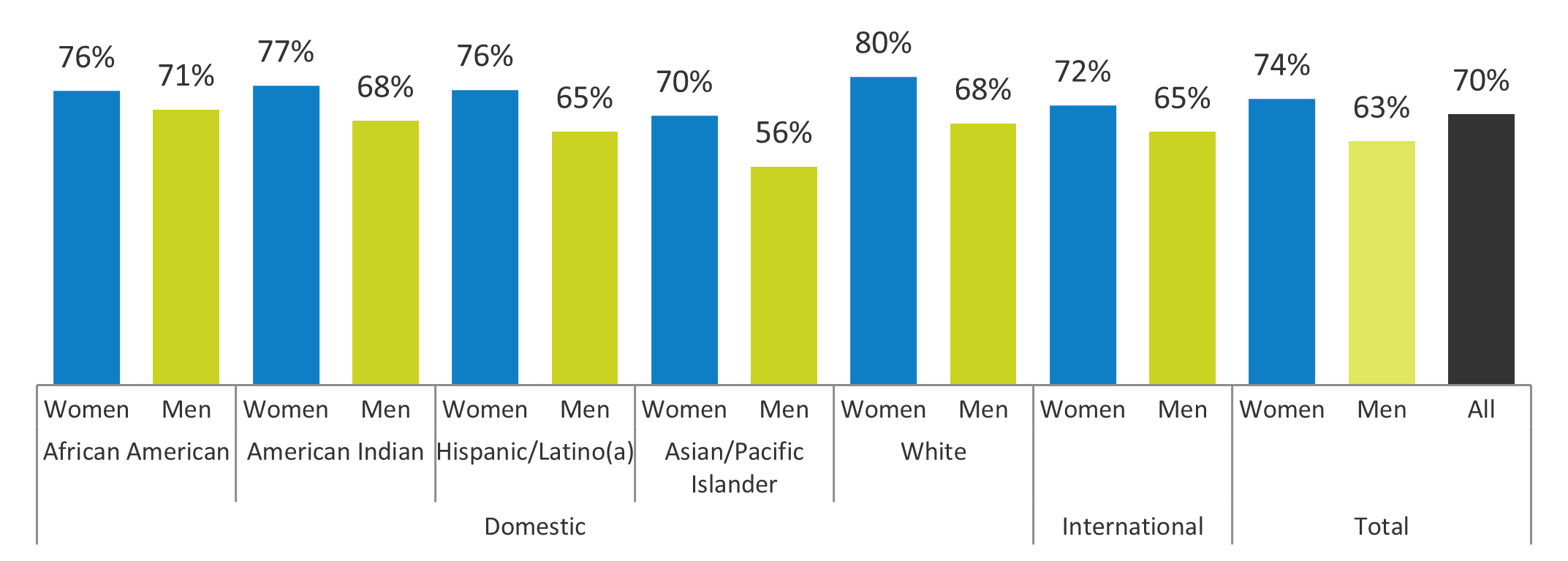

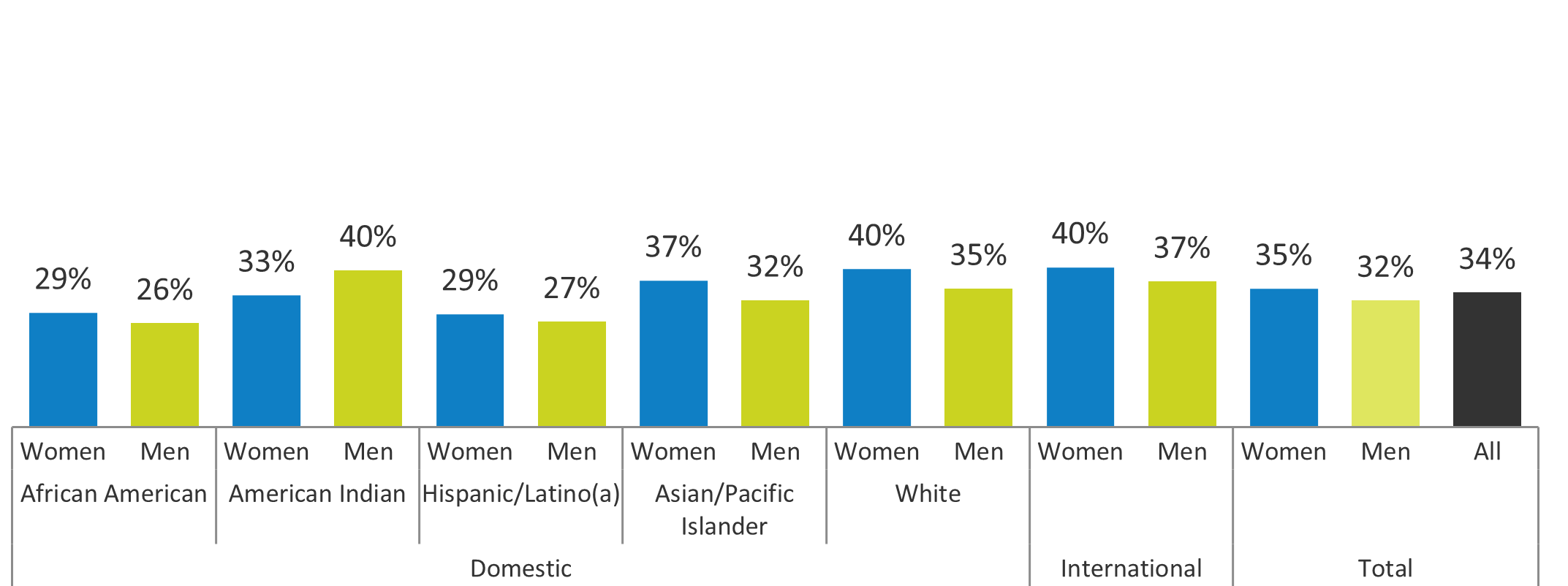

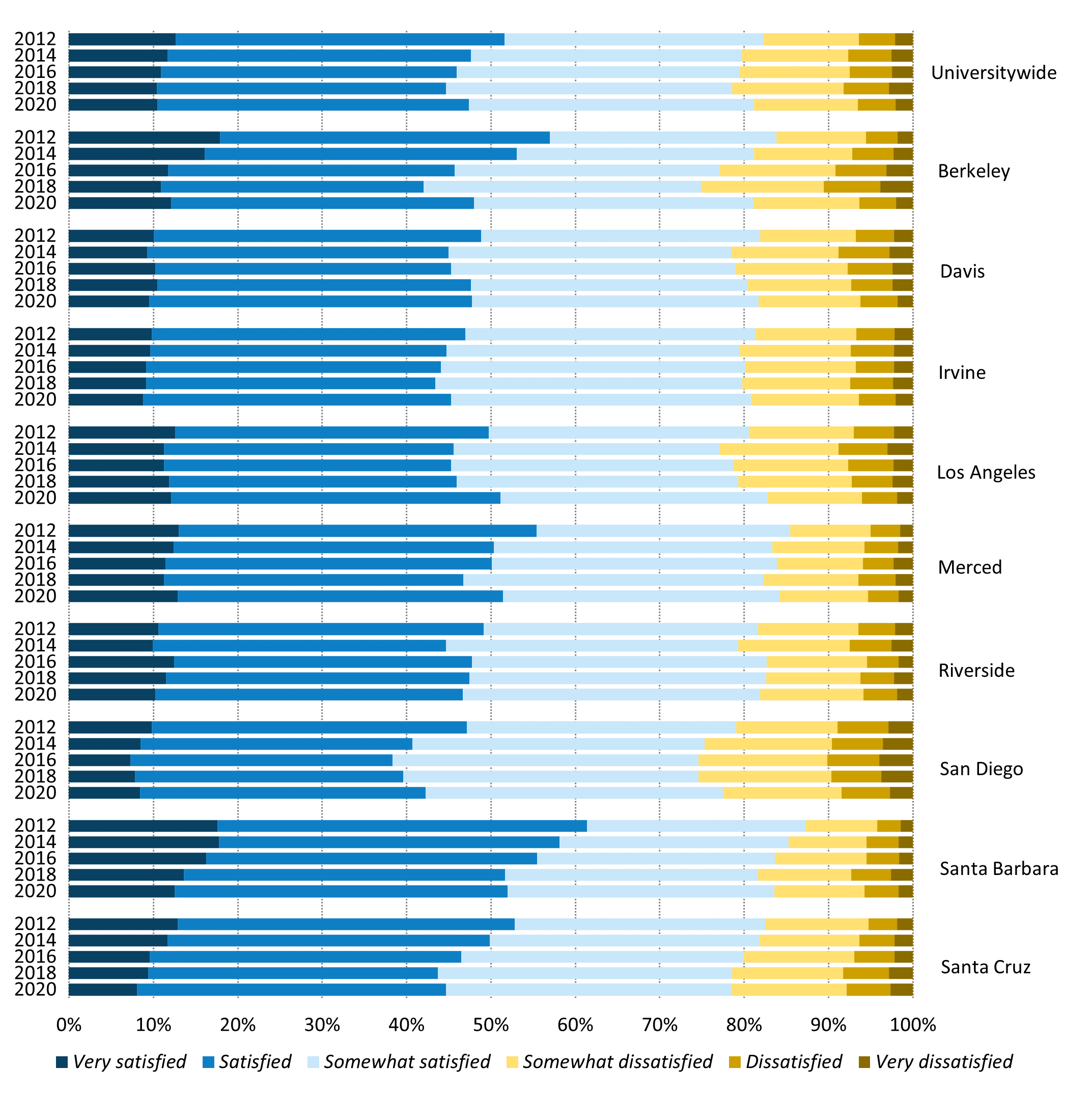

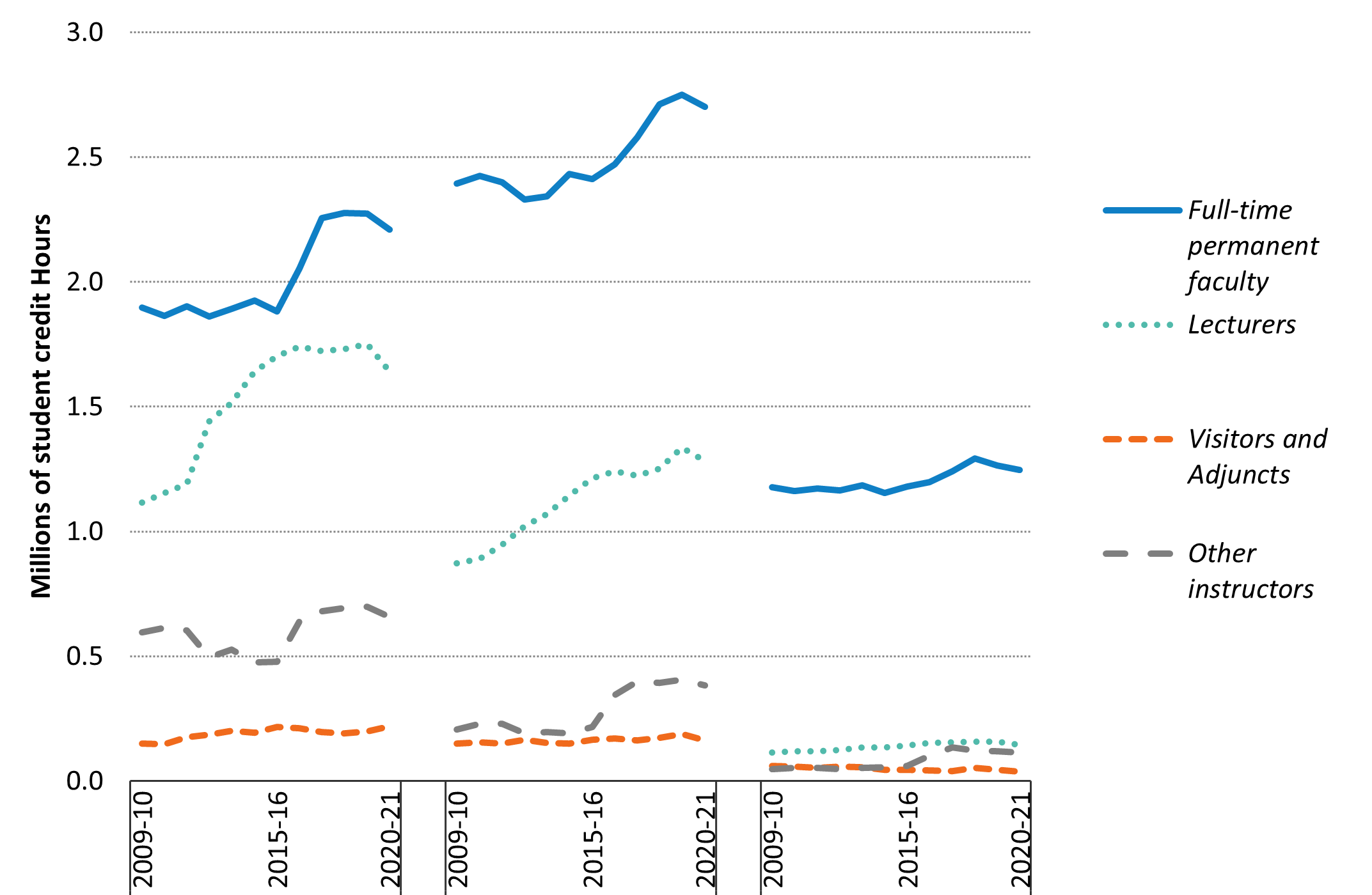

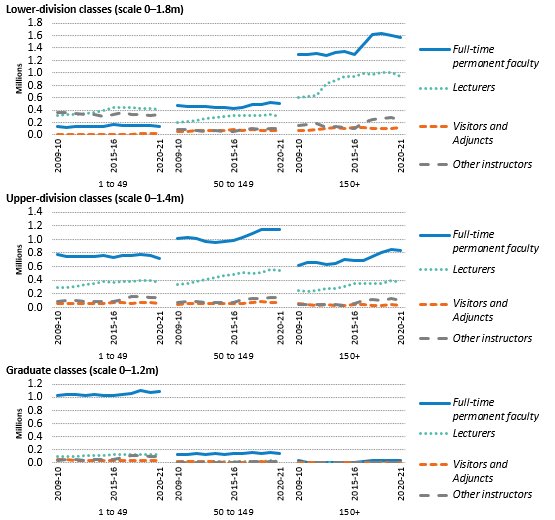

UC’s faculty are principally responsible for maintaining UC’s academic excellence and promoting student success. Student retention, graduation rates, and measures of effectiveness are presented in Chapter 3. This chapter focuses on the learning experience of UC’s undergraduate and graduate students, reporting what skills they have learned, their engagement with faculty and their peers, and satisfaction with their UC experience. A majority of both undergraduate and graduate students report improvement in academic skills. This chapter also reports on the composition and workload of instructional staff across different academic disciplines and professional programs.

Expanding learning opportunities beyond students on campus demonstrates the connection between the teaching and the public service missions of the University. UC Extension offers adult professional and continuing education programs to Californians and people around the world, enrolling hundreds of thousands of Californians in its programs each year.

Promoting educational effectiveness

UC is committed to continuous improvement of instruction and employs a range of pedagogical and assessment strategies to enhance and support student learning. Campuses offer pedagogical development and training for faculty and teaching assistants to promote the use of evidence-based teaching practices and improve the quality of teaching and learning. UC’s teaching and learning centers and offices of instructional development train hundreds of instructors each year, improving the quality of education for students in all disciplines across all ten campuses.

UC promotes educational effectiveness by supporting assessment of student learning. Assessment strategies include the development of program-level student learning outcomes and integration of evidence of student learning into academic program reviews. Programs across UC are undertaking curriculum redesign and improvement as a result of assessment work. Much of this aligns with the expectations of regional accrediting agencies, in particular the WASC Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC). As part of WSCUC accreditation, UC campuses assess five main core competencies of student learning: writing, oral communication, quantitative reasoning, information literacy, and critical thinking. Each UC campus posts its WSCUC accreditation reports online.

Innovative instructional offerings

UC faculty develop and teach an ever-expanding catalog of online courses and programs, expanding learning opportunities for UC and non-UC undergraduates, graduates, and professional students. Through the UC cross-campus enrollment system, UC provides undergraduates access to high-demand courses offered at other UC campuses, increasing flexibility and opportunities for degree completion.

For non-UC students considering matriculation at a four-year university or resuming their studies, UC offers for-credit online courses that may transfer to other colleges and universities. UC Extension offers online continuing education courses, professional certificates, and post-baccalaureate programs for those seeking to advance their education and to enhance their professional skills.

In addition to online courses, UC leverages instructional technologies to enhance instruction and promote success. UC continues to develop and refine hybrid courses using multimedia resources, videos, podcasts, e-books, and other technology-based tools. UC follows best instructional practices to embed innovative technologies into course design and focuses on creating online and face-to-face learning experiences that encourage collaboration and maximize faculty-student and peer-to-peer interactions. Increasingly, UC courses utilize a flipped model of instruction, where lectures and other traditional classroom content are provided online, and classroom time is dedicated to group discussions, problem-solving activities, and other experiential exercises.

Ongoing assessment and data-driven approaches to teaching and learning are integral parts of UC’s use of technology. Several UC campuses have adopted assessment systems that use online conceptual models and adaptive learning tools to determine students’ knowledge quickly and accurately. Based on responses to questions, the software determines concepts or topics where each student needs to focus. Assessment and LEarning in Knowledge Spaces (ALEKS) uses web-based adaptive tools to provide students with individualized feedback and learning pathways in entry-level math and chemistry courses. As part of the 2015 state budget framework agreement, three UC campuses engaged in a pilot study of the impact of adaptive learning technologies on student success and as a mechanism to strengthen instruction. The primary finding of the study was that when students use adaptive learning technology as intended, results are positive in relation to a student’s overall performance in the course to which it is applied.

UC is enhancing student learning opportunities and success by expanding summer course offerings (in-person and online) to reduce students’ time to degree and enrich their academic experience. Offering bridge experiences and orientation during summer also helps incoming students transition to campus life and prepare them for the rigorous courses at the undergraduate level.

the impact and lessons of the pandemic

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, UC campuses shifted almost all of Spring 2020 courses to remote instruction and most courses remained remote during the academic year 2020–21. Faculty and staff did a historic and commendable job adapting almost all courses to remote in a matter of days or weeks. Campuses ramped up efforts to provide students the necessary technology, along with academic and counseling support to help students succeed in this environment. UC has been collecting and will continue to collect data and research about learning outcomes during this period. Among the most significant impacts of remote instruction is that students, on average, increased the number of units they were taking per term and enrollment in summer session increased dramatically.

To keep the University community informed of the impact of the pandemic on instruction, a series of Regents items were presented with the most up-to-date information that was available at the time of presentation. In addition, remote instruction provided the opportunity for Regents’ presentations that focused more generally on best practices available within the University to improve pedagogy and student success with the goal of reducing equity gaps in learning. Here is a listing of relevant Regents’ items from the past two years:

- Update of Covid-19 impact on the University of California: academic and student Issues, May 20, 2020 (pdf)

- Planning and Evaluation of Covid-19 Academic and Student Impacts, September 16, 2020 (pdf)

- Twenty-First Century Skill Development for University of California Students, November 18, 2020 (pdf)

- The Future of Instruction: Designing Equitable Classrooms and Technology-Enhanced Learning at the University of California, January 20, 2021 (pdf)

- Using Curricular Innovations and Enhancements to Address Equity Gaps, March 17, 2021 (pdf)

- Fulfilling the Academic Mission: Academic Senate Survey of UC Faculty and Instructors About Their Experiences During the Pandemic, March 2020 to May 2021, July 21, 2021 (pdf)

- Instruction and Research at the University of California: COVID-19 Impact and Plans for Fall 2021, July 21, 2021 (pdf)

- Innovations in Assessment and Grading at the University of California, March 16, 2022 (pdf)

- Discussion Academic Integrity at the University of California, March 16, 2022 (pdf)

for more information

Campus websites (website)

Summer enrollment (dashboard)

UC Education Abroad Program (dashboard)

Undergraduate research experiences (dashboard)

Results of UC Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES) questions that were specific to remote instruction and other accommodations due to the pandemic (dashboard)

Pandemic-specific questions from the UC Graduate Student Experience Survey (dashboard)

Adaptive Learning Technology Pilot Report (pdf)