overview

Under California’s Master Plan for Higher Education, the University of California is delegated the primary responsibility in public higher education for doctoral education. For the health professions, this means that UC is the only California public institution authorized to grant the following professional degrees: D.D.S. (Doctor of Dental Science), M.D. (Doctor of Medicine), O.D. (Doctor of Optometry), Pharm.D. (Doctor of Pharmacy) and D.V.M. (Doctor of Veterinary Medicine). Along with other private educational institutions, UC also provides doctoral education leading to Ph.D. degrees in Nursing and Public Health, as well as the Dr.P.H. (Doctor of Public Health) degree.

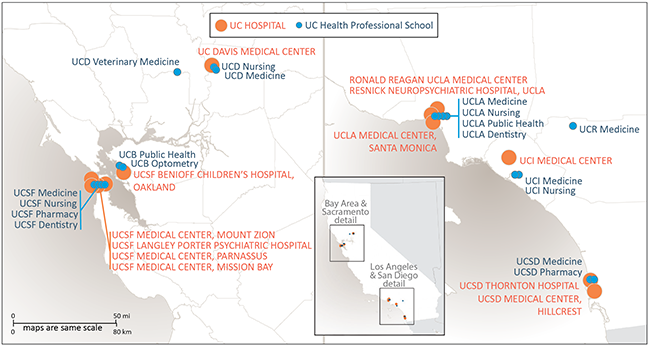

UC’s health sciences programs are national and international leaders in teaching, research and clinical care. In support of these programs, UC provides leadership and strategic direction to advance the missions of the University’s 18 health professional schools and 12 hospitals, referred to collectively as UC Health.1

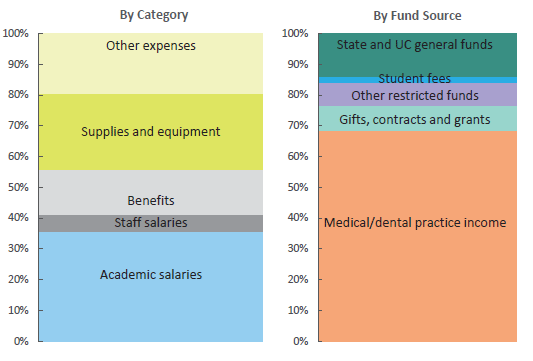

A significant portion of UC’s mission of instruction, research and public service, as measured in terms of operating expenditures is within the health sciences. In 2015–16, expenditures for delivery of health care services at UC Health medical centers, including UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, rose to about $10.2 billion, more than one-third of the University’s total operating expenditures. Other major UC Health expenditures include $2.7 billion for instructional activities and $2.2 billion spent on research.

In fall 2016, about 42 percent of all UC faculty worked in health science disciplines. (More information about the health science faculty is presented in Chapter 5 – Faculty and Other Academic Employees.)

In fall 2016, 42 percent of postdoctoral fellows were in health science disciplines.2

Educating health care professionals

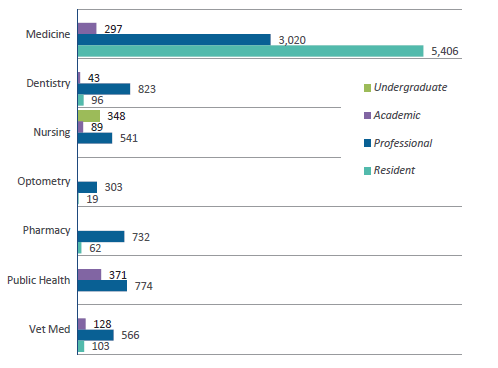

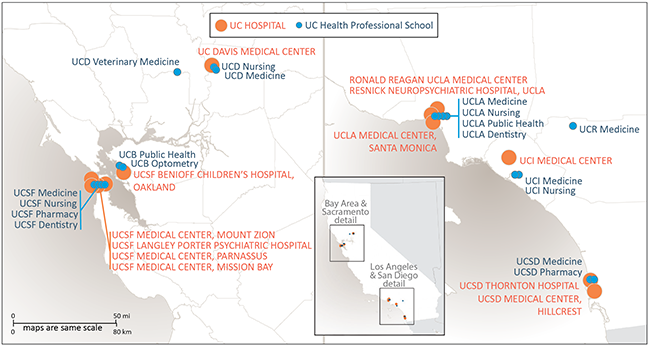

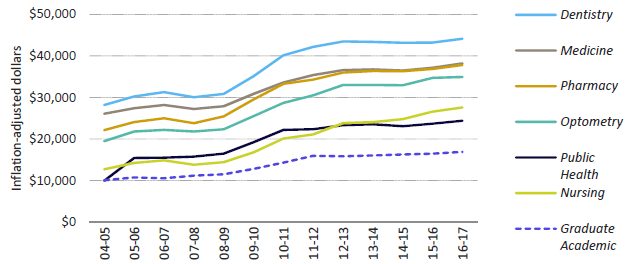

The University of California operates the largest health sciences instructional program in the nation, enrolling more than 14,000 students annually. The systemwide instructional program includes six schools of medicine and three smaller medical education programs (located at Berkeley, in Fresno and at the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles); four schools of nursing; two schools each of dentistry, pharmacy and public health; and one school each of optometry and veterinary medicine. The long-standing medical education program that operated jointly between UC Riverside and UCLA for more than 30 years transitioned in 2013 to an independent UC medical school.

A focus on medical research

Health science research expenditures represent the single largest disciplinary focus of UC’s research enterprise. Half of UC’s total research expenditures, about $2.2 billion, were for medical research, including related health scien ce fields such as public health and veterinary medicine. More than half of the funding for this medical research was provided by federal agency awards to UC.

Clinical trial research is an increasingly important component of UC’s medical research enterprise. UC initiated over 3,000 clinical trials over the last five years, with more than 2,700 underway during 2015–16. Of the $2.5 billion UC received that year in medical research awards, about 20 percent of the total was targeted for clinical trials, and 88 percent of these projects were sponsored by businesses.

These clinical trials occupy a unique position in UC’s research enterprise. They represent the final stage in the journey from a scientific discovery or innovation to an effective therapy or treatment that could significantly enhance global health.

Keeping California Healthy

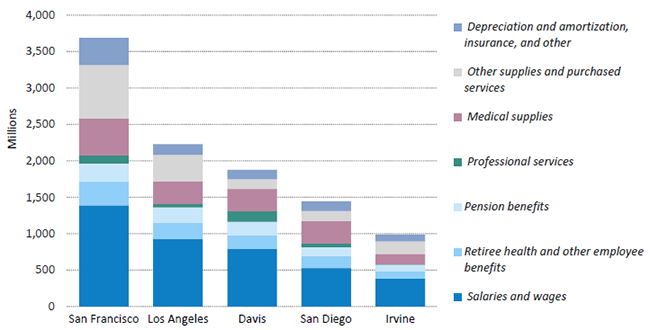

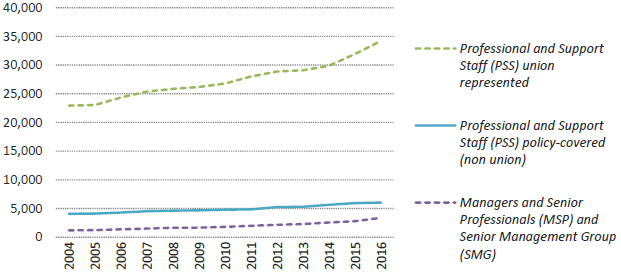

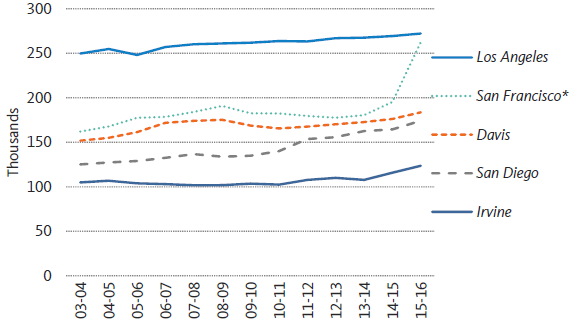

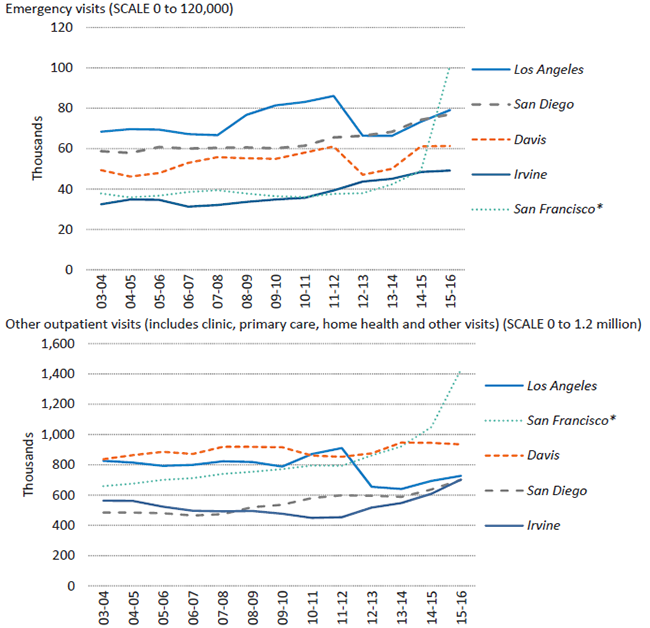

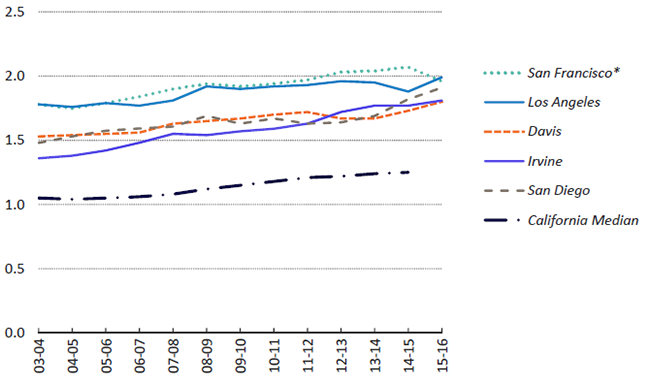

The University of California’s five academic medical centers (Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco) provide a vast resource for the clinical training programs of UC health professional schools. These centers prepare future generations of health professionals; they catalyze major advances in biomedical and clinical research; and they collectively serve as California’s fourth-largest health care delivery system, with about 42,000 employees, including 12,000 nurses. UC operates or staffs five major trauma centers, providing half of all transplants and one-fourth of extensive burn care in the state. In 2015–16, UC medical centers managed 368,000 emergency room visits and nearly 4.9 million outpatient visits, as well as more than 167,000 inpatient admissions resulting in more than one million inpatient days. More than 60 percent of UC patients are covered by Medicare or Medi-Cal or lack health insurance. In support of the University’s teaching, research and public service missions, UC health programs also maintain active relationships with more than 100 affiliated Veterans Affairs facilities, as well as county and community-based health facilities located throughout California.

In view of the size and contributions of health-related programs across the UC system, select performance indicators related to students, faculty and research are included both in this chapter and in the respective sections of this report that are devoted to those subject areas. For example, indicators related to students enrolled in UC professional degree programs are also included in Chapter 4 (Graduate Academic and Graduate Professional Students). Chapter 5 (Faculty and Other Academic Employees) includes indicators related to UC faculty appointments, headcounts and conferral of doctoral degrees. Information regarding diversity is found in Chapter 7 (Diversity). Research workforce indicators for medicine and health sciences, as well as indicators for general funding and expenditures, are included in Chapter 9 (Research — Increasing Public Knowledge).

In addition, this chapter includes information and performance indicators for various aspects of the University’s health sciences system, including health professional degree students, and health sciences instruction and research expenditures. This section also includes a number of indicators and metrics related to the University’s health care delivery system.

Looking forward

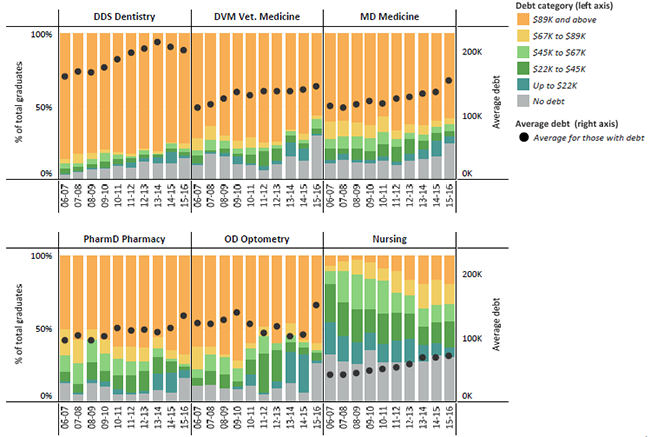

California’s population is growing, aging and increasing in diversity. Already the most populous state in the nation, California’s population is projected by the Department of Finance to grow 30 percent from 2016 to 2060. Statewide shortages and maldistribution of health care providers already exist in many health professions. These challenges will grow as health care reforms drive increasing demand for quality and accountability in the delivery of health services. At a time of unprecedented budgetary challenges, the financial success of UC medical centers has been an important resource for helping to back-fill diminishing state support, primarily for UC schools of medicine. However, the changing environment for health care signals changes that threaten this financial success and the ability of the medical centers to help support the academic mission. Among these financial challenges are reductions in federal and state spending for programs such as Medicare, Medi-Cal and the National Institutes of Health, and challenges associated with the implementation of health care reform.

Notwithstanding these challenges and the uncertainties related to health care reform, UC Health is working to support other major endeavors to help meet current and future health care needs. Significant among these, the long-standing medical education program that operated jointly between UC Riverside and UCLA for more than 30 years transitioned in 2013 to an independent UC medical school. The first new allopathic (M.D.-granting) medical school to open in California in more than 40 years, UC Riverside School of Medicine will graduate its first class of students in summer 2017. Of UCR’s inaugural class of medical students, 100 percent matched into a residency program; thirty-three of the 40 students will be staying in California; 10 matched in residency programs in inland Southern California. Also of note, in January 2017, UC Irvine received approval to transition its Program in Nursing Science to the Sue and Bill Gross School of Nursing at UC Irvine.

To recognize and accelerate implementation of innovative practices in clinical care, UC Health launched the UC Center for Health Quality and Innovation in 2010. The center promotes innovations in clinical care that improve patient outcomes and quality of care within the UC system and beyond. These and other activities are among the many initiatives now underway across UC to help improve quality, access and value in the delivery of health services.

Leveraging Scale for Value

The Leveraging Scale for Value (LSFV) initiative is the systemwide approach to creating value and improving outcomes. LSFV includes work on revenue cycle, supply chain and information technology. LSFV delivered $179M in savings for FY 2015, $373M for FY 2016 and is on track to deliver $280M for FY 2017.

UC Health's governance model

In November 2015, the University of California Board of Regents adopted amendments that streamlined the oversight of UC Health to support the continued growth of UC’s academic medical centers. The Regents’ governance of UC Health continues through a restructured Committee on Health Services, with seven voting regents and eight non-voting advisory members who are leaders in health care delivery, health policy and academic medicine. The committee provides strategic direction and oversight, makes recommendations to the Board, and takes action pursuant to delegated authority, on matters pertaining to the university’s health professional schools, academic health centers, health systems, non-hospital clinics and student health and counseling centers.

1 Data in this chapter exclude UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland except where noted.

2 Statistics are by headcount rather than FTE. Headcount numbers tend to be larger than FTE, especially in the health sciences, because non-ladder-rank health science faculty, such as clinical faculty, are more likely to have joint or partial appointments.

FOR MORE INFORMATION