When Ebelechukwu Eseka (“Ebele” for short) emigrated to the U.S. from Ghana as a sophomore in high school, her strategy was to keep quiet and try to blend in. She was reluctant to speak up, even when she was put into classes that were far beneath her academic ability.

Eseka was named a Promise Scholar at UC Santa Barbara, a program the provides financial help to high-achieving, first generation students from low-income households. She also benefitted from Pell Grant funding and state aid that allowed her to graduate without debt and take advantage of internships and leadership opportunities that built her confidence and taught her to speak out.

As a second-year student, she participated in the UCDC program, where she worked as an aide in Dianne Feinstein’s office. “It was an amazing experience, and a little terrifying,” she said. “People were calling the office constantly. I got to learn what Californians are thinking and what’s important to them.”

She now plans to apply to law school to become an immigration attorney. Her ultimate goal: create a nonprofit that combines legal aid and paperwork processing help with other support services to help immigrants find their footing in their new country. “It’s a big goal, but I know it’s achievable,” she said.

“Freshman me was so timid, silenced by the challenge of immigration and fitting in. Now I ask a lot of questions, I’m not afraid to take risks and try new things. I found my voice at UC Santa Barbara. I am so proud of who I am today!”

Goals

The goal of the University’s undergraduate financial aid program is to ensure that the University remains accessible to all academically eligible California students, regardless of their financial resources.

Affordability is among UC’s highest priorities. The University has maintained a strong record of enabling families from all income levels to finance a high-quality education, and it closely monitors the impact of its pricing decisions and financial aid programs.

Maintaining inclusive access

The total cost of attendance and the composition of undergraduates in terms of financial resources set the framework for what is required to provide adequate financial support.

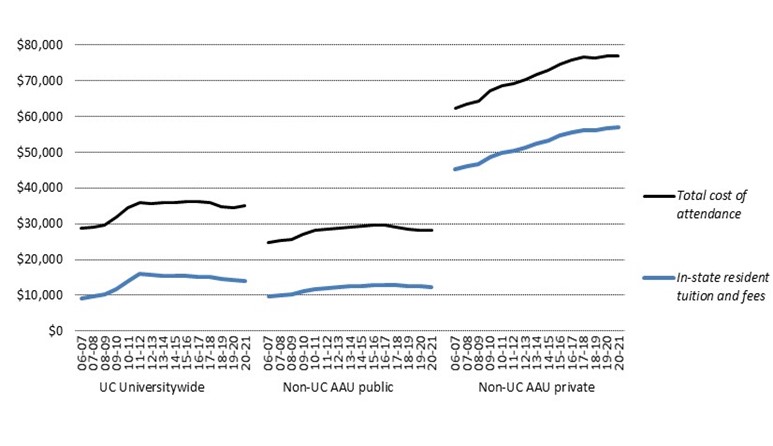

For in-state students who live on campus, the total annual cost of attendance, which comprises tuition and fees and other expenses (e.g., living and personal expenses, books and supplies, transportation, and health care), has remained relatively flat over the last several years, ranging from $35,000 to $41,000 across UC. This figure compares to about $27,000 on average at other Association of American Universities (AAU) public institutions and around $71,000 for the AAU private institutions (2.1.1).

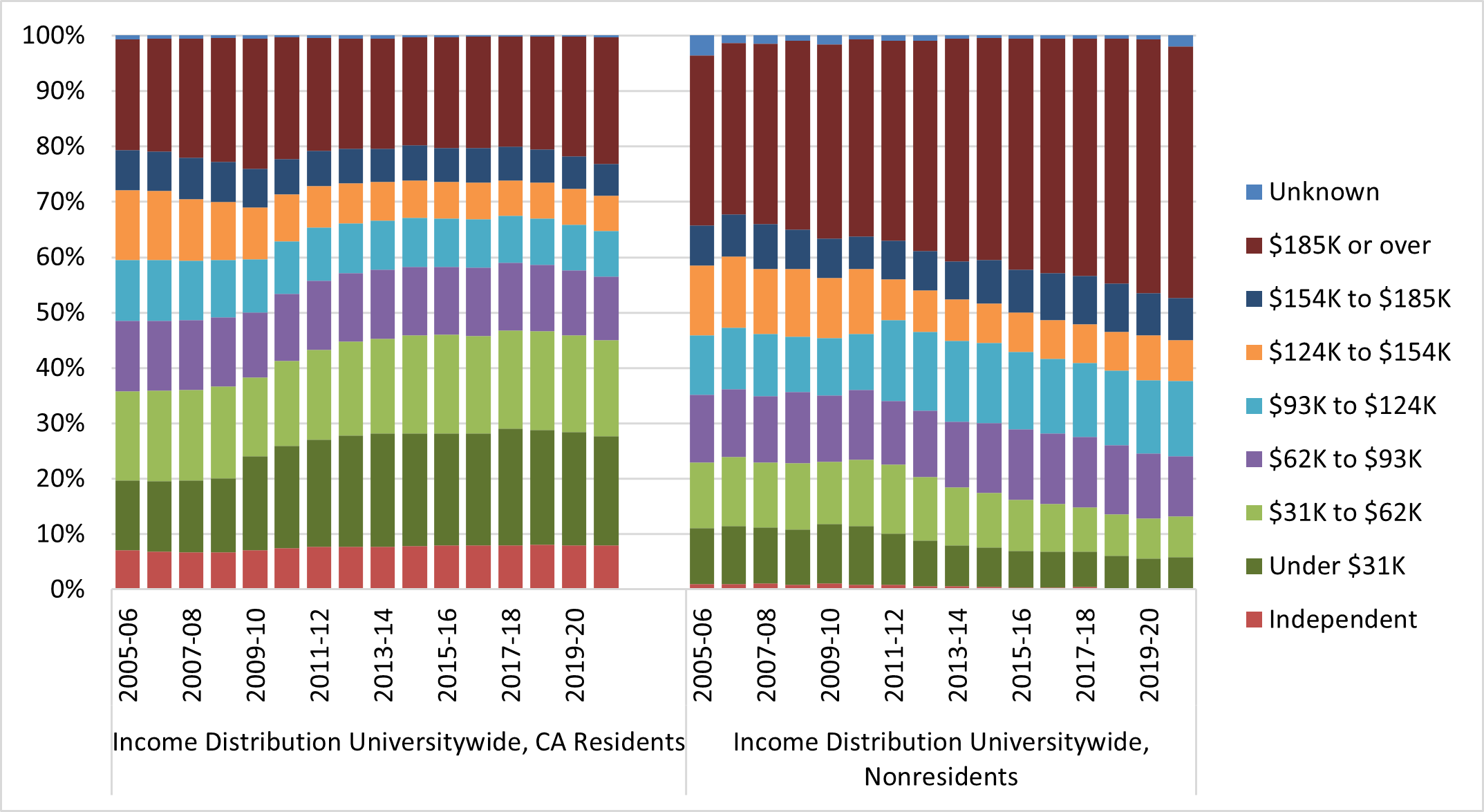

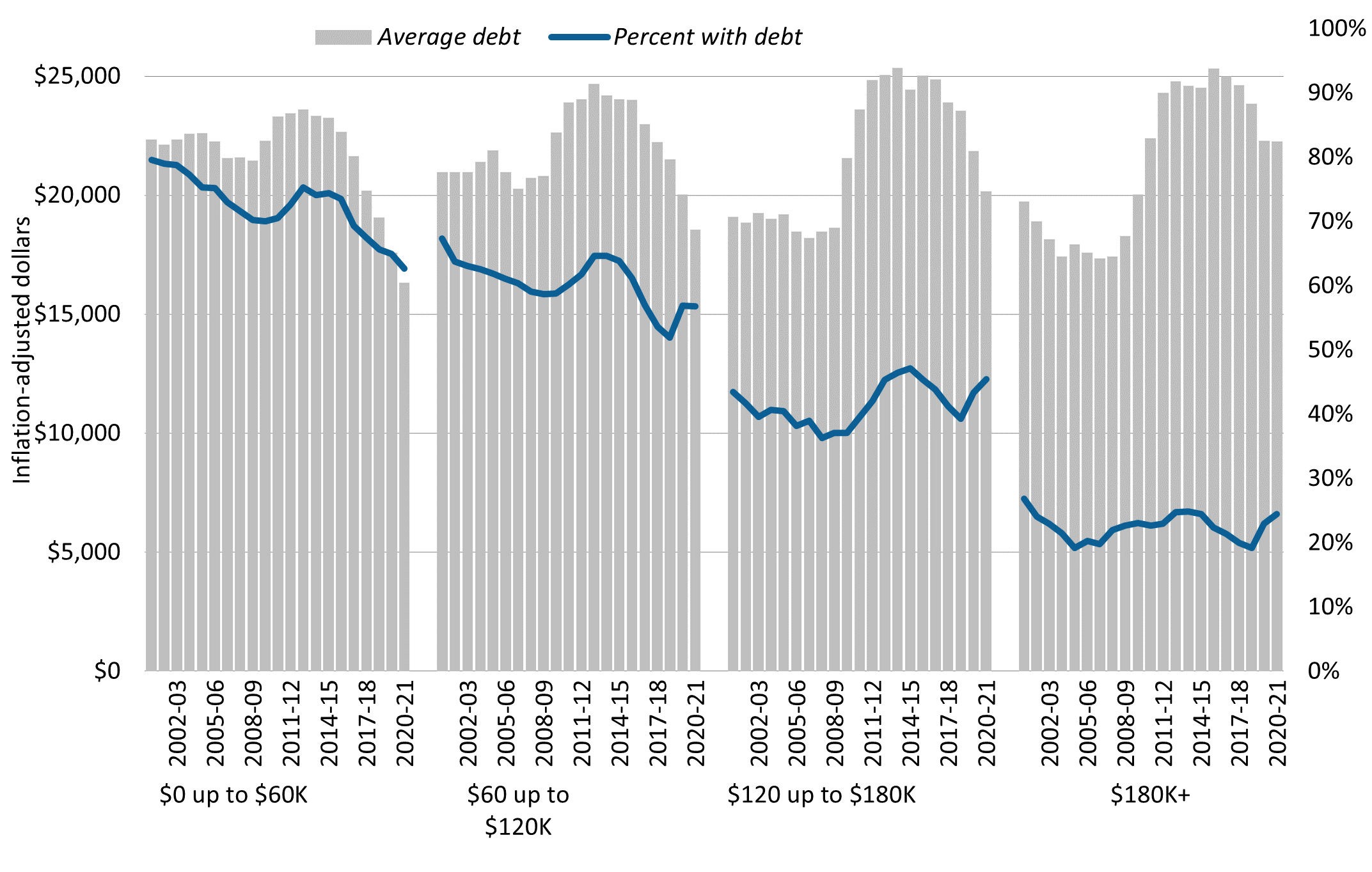

The income profile indicators demonstrate that the University remains accessible to low-income students. Between 2008–09 and 2020–21, the proportion of UC in-state undergraduates in the lowest income categories increased from 30 percent to 37 percent, with offsetting declines among middle- and upper-middle-income families (2.2.2). These trends reflect both the manageability of UC’s net cost for low-income families, and the decline in the incomes of UC families since the 2009 economic recession.

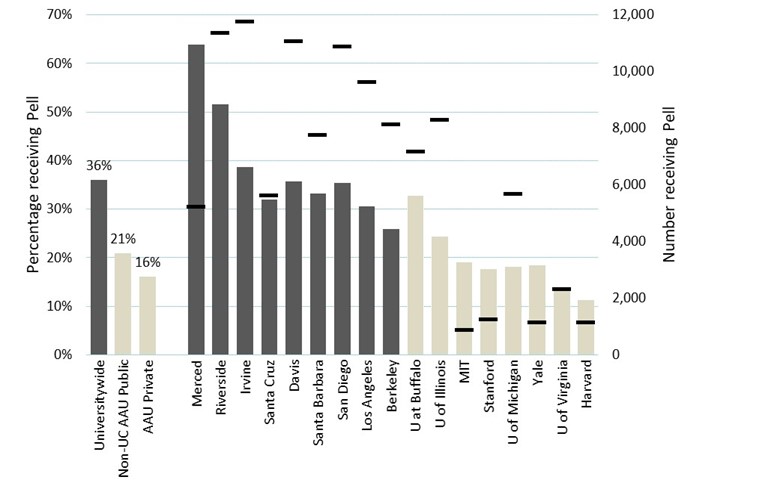

In fall 2021, 34 percent of all UC undergraduates received a Pell Grant, which is a federal grant for low-income students with family incomes typically under $50,000. Pell Grant recipients comprise a higher share of UC’s student body than they do at both AAU public (21 percent) and AAU private (16 percent) institutions (2.2.1).

Financing a UC education

UC is able to provide access to students across the economic spectrum thanks to a financial aid program that considers how much parents can afford; federal, state, and University gift aid or grants; and a manageable student “self-help” contribution from work or borrowing.

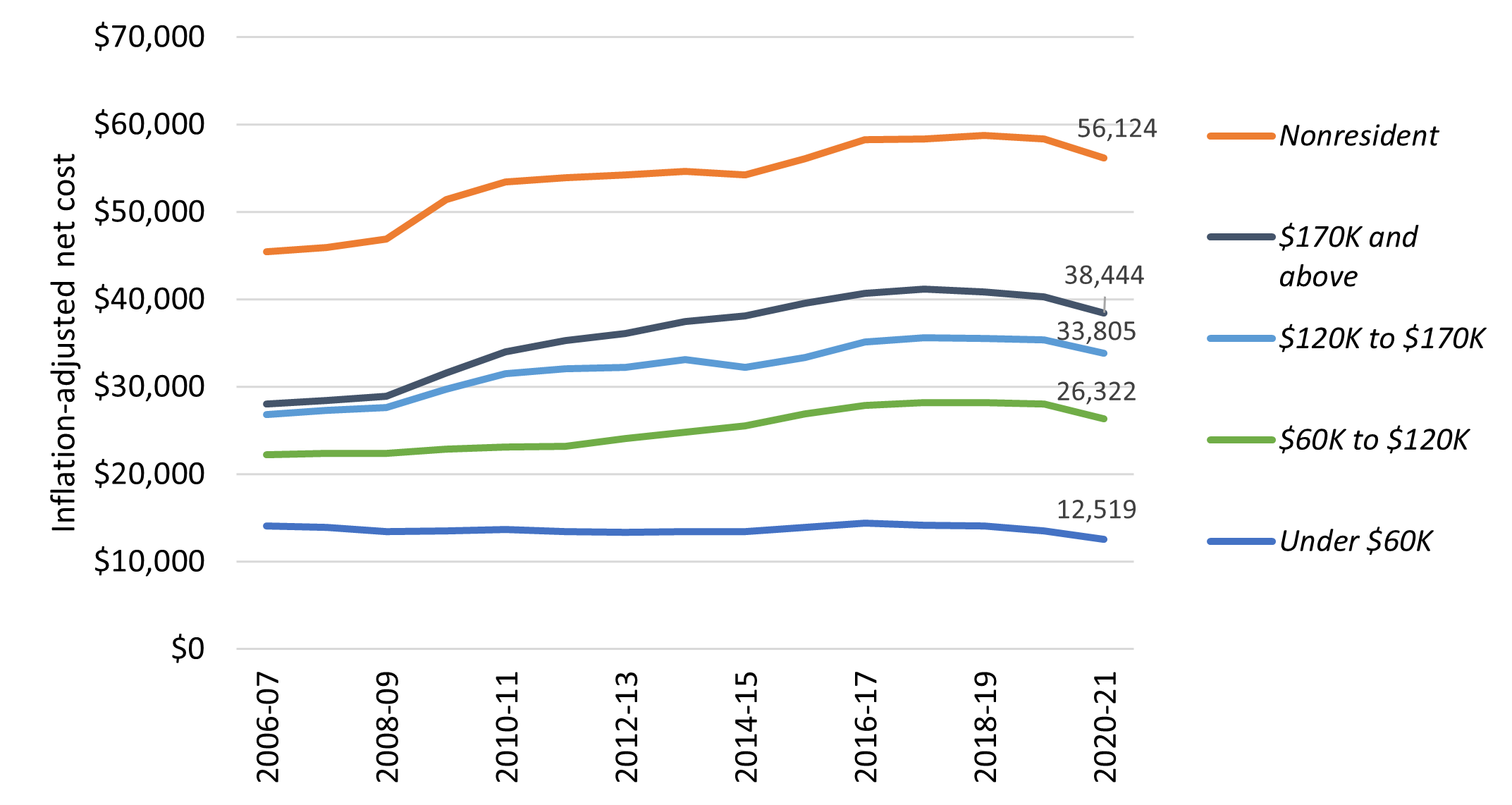

Gift aid dramatically reduces the net cost of attendance (total cost of attendance less gift aid) for students and enables those from low- and middle-income backgrounds to enroll in sizable numbers and proportions. The resulting inflation-adjusted net cost of attendance for in-state students from families in the lowest income bracket (less than $60,000) has declined or remained stable since 2004–05.

Federal and state governments provide critical support through the Pell Grant and Cal Grant programs. In addition, UC’s commitment to affordability is evident in the University’s strong systemwide financial aid program. As a result of this robust institutional financial aid program, which combines support from different sources, 55 percent of California resident undergraduates paid no tuition in 2020–21. Furthermore, over two-thirds of UC’s own grant program helps students cover non-fee costs such as room, board, and book expenses.

Both UC and the State of California have made it a priority to provide financial support to undocumented students, with 2020–21 marking the tenth year that state and University financial aid has been available to undocumented Californians. Approximately 4,200 undocumented students received Cal Grants or need-based UC grants in 2020–21, totaling $90 million. The California Dream Loan Program continues to provide student loans to undocumented Assembly Bill (AB) 540 students at CSU and UC.

The Legislature has provided $2.5M in UC’s annual budget for the Dream Loan program, which has been matched by UC’s own funding of $2.5M each year. Undocumented students who qualify for a waiver of nonresident supplemental tuition under AB 540 have been eligible for Cal Grants and UC grants since 2013 under the California Dream Act.

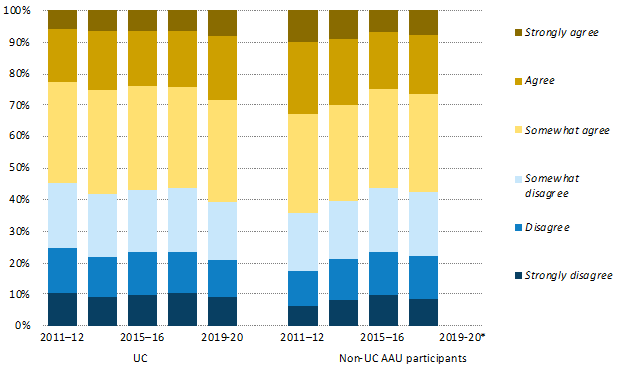

An undergraduate’s self-help requirement can be met through a combination of work and loans. UC relies on student surveys — including the UC Undergraduate Experience Survey (UCUES) and Cost of Attendance Survey — to measure how much students work. UCUES data show that over 50 percent of undergraduates do not work. Studies indicate that 20 hours of work per week is the threshold at which undergraduate academic performance may be adversely affected, and UC’s financial aid programs are structured to expect no more than 20 hours. Nevertheless, in the most recent UCUES survey (2020), ten percent of students reported working more than 20 hours per week, the same share as two years earlier.

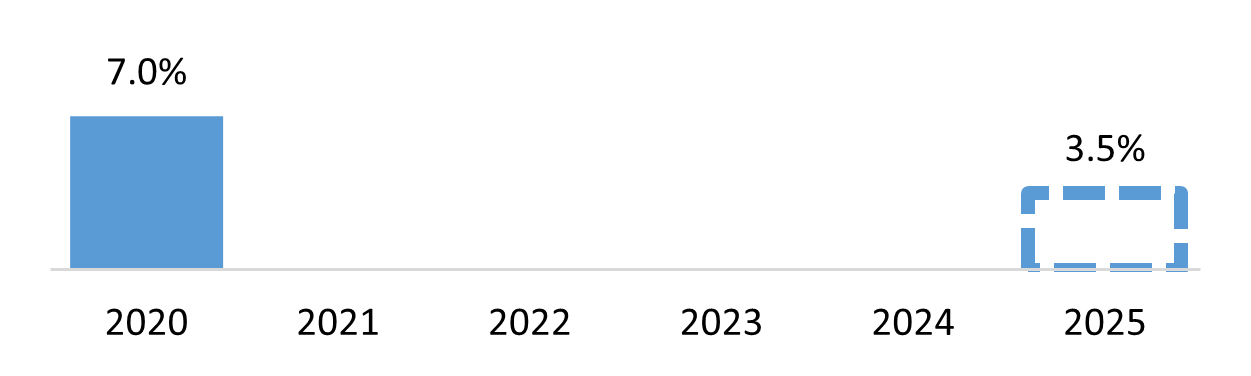

For the academic year 2020–21, about 25 percent of California undergraduates relied on federal student loans to help finance their education, with loan amounts averaging $5,900. Federal borrowing declined significantly in 2020–21 due to a number of pandemic-related factors, including lower student budgets as a result of living at home or off campus; more federal grant support from Higher Education Emergency Relief) (HEERF) grants; and COVID Emergency grants from the state of California and the University for undocumented students. Parental borrowing under the federal PLUS program also declined to about four percent, with the average PLUS loan amount increasing to about $19,200 per year.

Since 2014–15, California’s Middle Class Scholarship program has provided a new source of gift assistance for students at UC and the California State University with household incomes of up to $191,000 who receive limited or no need-based financial aid. In 2020–21, UC students received $37 million in Middle Class Scholarship awards.

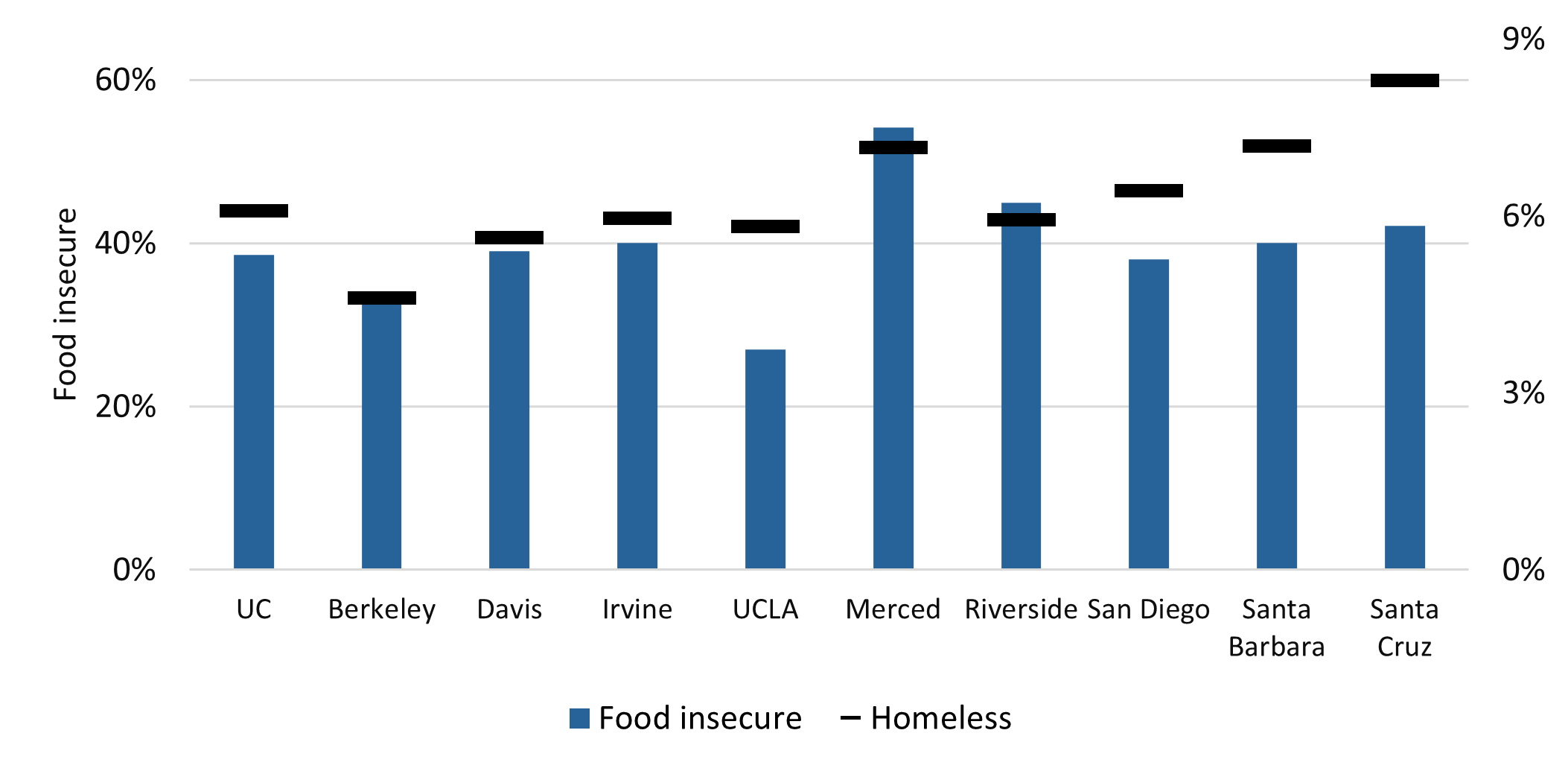

Addressing basic needs

Universities across the nation are attempting to address student basic needs. UC provides unprecedented access to low-income students and has prioritized efforts to address food and housing insecurity. Spring 2020 UCUES survey results show 39 percent experience low to very low food security (20 percent report very low food security) and four percent report being homeless. The UC Office of the President (UCOP) has partnered with UC Systemwide Basic Needs Committee members to share data collection efforts and findings with intersegmental groups, including our California State University and California Community College colleagues, and has presented survey results to the UC Board of Regents Special Committee on Basic Needs.

The Regents Special Committee on Basic Needs issued a series of recommendations related to assessing and supporting student basic needs. Among the recommendations was to expand UC student access to the state CalFresh program. To facilitate this, the Committee recommended conducting research on the barriers to CalFresh eligibility and trends in CalFresh enrollment across the UC system. UCOP is partnering with the California Policy Lab to conduct research on student participation in the CalFresh program, with findings expected in 2022. Furthermore, UC Financial Aid Offices contacted students who were eligible to apply for CalFresh during the 2020–21 and 2021–22 academic years to encourage them to apply.

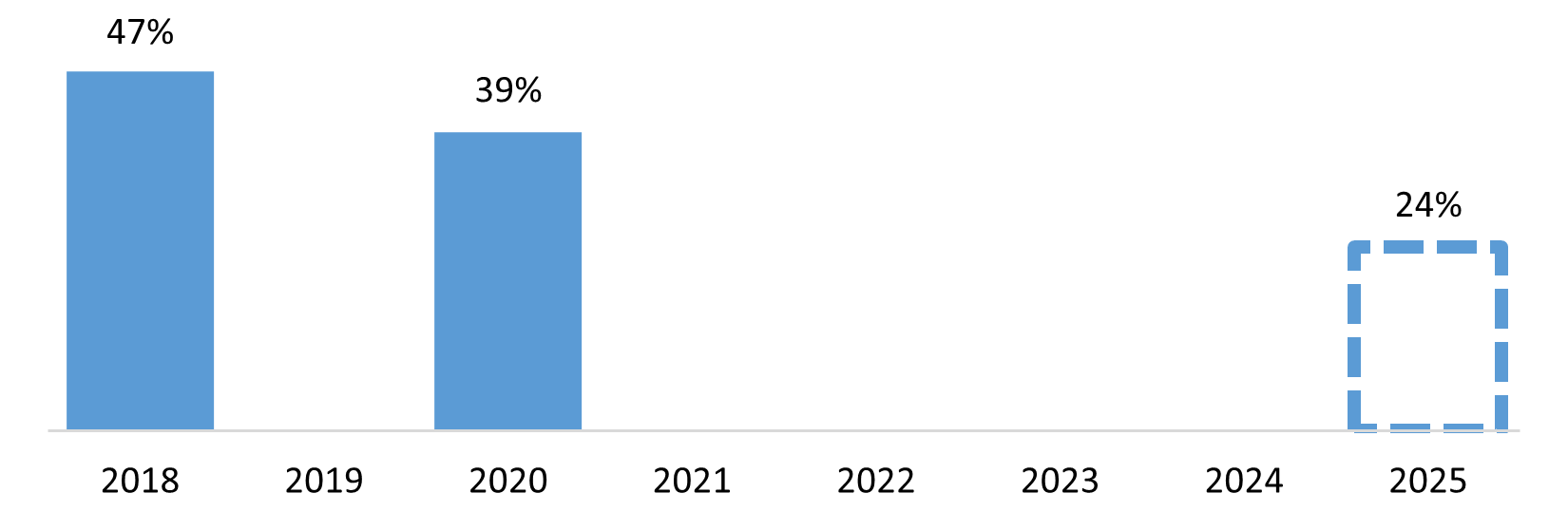

Limiting cumulative debt

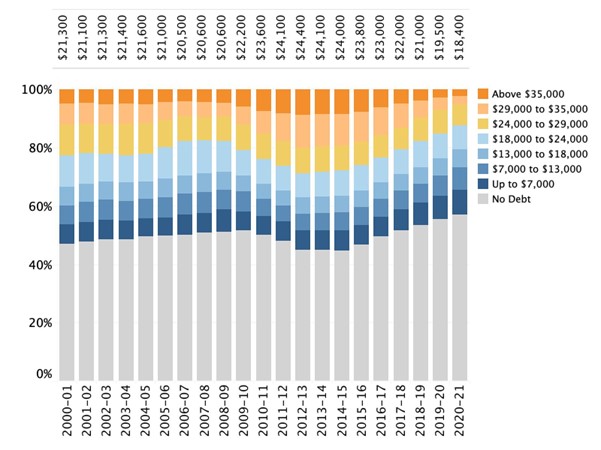

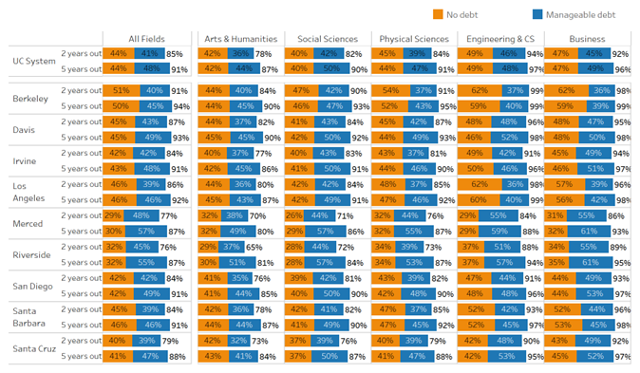

The proportion of undergraduates leaving with debt is lower than a decade ago. About 43 percent of the class of 2020–21 graduated with debt, with an average amount of $18,400. This translates into a monthly repayment amount of about $195 for ten years at a five percent annual interest rate. This level of debt is manageable, considering that a typical graduate who takes out loans earns about $3,500 a month within two years after graduation (2.3.5). Cumulative debt declined in 2020–21 due to the lower levels of borrowing in the most recent year due to the pandemic-related factors noted above. The most recent comparison data show average debt of $27,500 for public four-year institutions and $33,400 for private nonprofit four-year institutions (2.3.7). UC President Michael Drake has also created a debt-free path to UC that would eliminate the need to borrow for qualifying students.

pandemic impact

The 2020 COVID pandemic disrupted the University’s education delivery, moving nearly all courses online. The pandemic also had several impacts on students, parents, and how they paid for college costs. Both graduate and undergraduate students were impacted and both received emergency grant support from the federal government, the State of California, and UC.

Students who were living in on-campus housing were largely forced to move home with their families or into off-campus housing. Those who would have faced hardship moving off-campus were provided with accommodation. Because living off-campus and, particularly, with their families, is less expensive, the aggregate financial need for students was reduced. This reduction in aggregate need extended into 2020–21.

The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and Higher Education Emergency Relief Funds (HEERF) Act provided $69 billion directly to colleges and universities. In 2020–21, UC campuses received $112 million through HEERF grant awards, providing an average of $1,100 to 111,000 recipients. UC and State funds supplemented CARES emergency grants with $4 million to provide equivalent support for undocumented students, which provided an average award of $1,200 to 3,340 students.

Looking forward

In 2021, the Board of Regents approved the Tuition Stability Plan. Beginning fall 2022, tuition will be adjusted for each incoming undergraduate class but will subsequently remain flat until the student graduates, for up to six years. For undergraduates who first enrolled in fall 2021 or earlier — including all current undergraduates — tuition will stay flat at current rates for the duration of their enrollment, up to six years. Furthermore, the proportion of new tuition revenue set aside for financial aid will increase from 33 percent to 45 percent, expanding the University’s own need-based financial aid. For graduate students, tuition will remain flat in constant dollars, adjusted annually for inflation.

For more information

UC costs and financial aid, including financial aid estimators (website)

Trends in UC financial aid (website)

Financial aid awarded by year, campus, and award type (dashboard)

Total and net cost of attendance by campus and residency (dashboard)

Typical student debt, earnings, percentages of graduates with debt, and debt payoff calculators (dashboard)